ISSUE № 5: DIGGING

DIGGING

Illustration by Kelsey Martin of Kettle Pot Paper

November 21, 1996, was the last day the crew from Intersal could search the waters around Beaufort Inlet. On the following day their search permit would run out, and they would have to reapply, returning to home to wait out the cold season and application process. Intersal (a salvage/recovery company) had roamed the Beaufort area seeking three particular shipwrecks on and off for eight years and studied them for even longer. Using a magnetometer to scan the inlet floor, Intersal's team could tell that there were a few particularly intriguing anomalies (potential wrecks) piled up on the floor of Beaufort Inlet, and focused their efforts on exploring those sites. On the last day, they decided to double-check a site that had been obscured by silty, stirred-up water earlier in the expedition. A series of three divers spotted cannons and an anchor rising up from the sand — a promising start. It would take years to truly confirm what they all suspected on the day of discovery: These were the remnants of Blackbeard's Queen Anne's Revenge.

Although not as evident as an anchor or a cannon, artifact QAR1445.009 and hundreds of thousands of others also awaited discovery, buried, lodged, resting in the scattered wreckage.

Need to catch up on the other installments before continuing on?

When Intersal first set out to search North Carolina's waters, it was not with an eye towards the Queen Anne's Revenge, but on El Salvadore, a Spanish ship wrecked in 1750 while carrying a fabulous load of gold and silver to Cadiz.

"Phil [Masters] was a Marine," Intersal’s current president and CEO Reeder described its late founder and president. "People who know Marines don't really have to extrapolate on that too much … I wouldn't call Phil an introvert. He was reserved at times, but not generally. He was very enthusiastic about what became his passion, which was finding El Salvadore, and pretty much dedicated himself to that at the exclusion of a lot of other things." From the early days of their acquaintance, Reeder remembers talk of gold, pirates, and El Salvadore filling poolside conversation as they sipped tequila. Masters's dedication to the project even took him as far abroad as an archive in Seville shortly after he and Reeder met.

An aside: Carl Cannon, Blackbeard interpreter and longtime resident of the Beaufort area, says that his father and other locals could have pointed out where the Queen Anne's Revenge was years ago. He says the general area was local knowledge, passed down through many generations of fishermen, and that trawlers would occasionally get hung up on the site.

During Masters's hunt for traces of information on El Salvadore and its location, a helpful state employee pointed him towards a copy of Dave Moore's prospectus on the Queen Anne's Revenge - where it might be, what it would take to find it, and a theoretical plan for recovery. North Carolina's own Department of Cultural Resources (now the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, or DNCR) had done some preliminary research in the early eighties, poked around in the inlet a bit, and found nothing. Moore says that at the beginning it was pulling teeth to get the state interested.

"That's part of the irony of the whole damn thing."

Although initially less-than-thrilled that his research had been handed over to treasure hunters (a description that Reeder does not necessarily eschew), Moore developed a longstanding friendly relationship with Intersal, and was one of their first calls to shore on November 21st.

"This time," said Mike Daniel, Intersal's director of operations, "I think I really found your wreck." (Clarification was necessary because thanks to an earlier prank call, he was the boy who cried pirate shipwreck).

State archeologists dove the site the day after its discovery, on November 22, 1996 — the anniversary of Blackbeard's death. Everyone wanted to believe they'd found Blackbeard's ship. That hope, however, was tempered by the knowledge that when almost any mysterious nautical material appeared anywhere in the state, a Blackbeard legend usually attached itself to the artifact — even when it stretched believability. So when the divers pulled up a bell and other artifacts after spotting a cannon or two on the wreck, state archeologists held their collective breath, waiting to see if it disproved the Queen Anne's Revenge theory. Bells were often marked with a ship's name and the date — if the date was after 1718, that positively ruled out the wreck having anything to do with Blackbeard. Back at the DCR's underwater archeology hub near Wilmington, conservator Leslie Bright worked on the bell, slowly removing corrosive buildup. Archeologist Richard Lawrence recounted it as a moment of truth: First a one appeared, then a seven, then — deep breath — a zero followed by a five, and the inscription IHS Maria, or Holy Name of Jesus, Mary, a common religious marker for the time.

An aside: Dr. Joseph Wilde-Ramsing (Mark's son) wrote that the sound of a bell is composed of five notes ringing out at once. He quotes Spanish sound analyst Dr. Llop i Bayo: "Bells represent the living music of the past because they are the only instruments that can retain their original sound throughout the centuries. The restoration of this bell is magnificent, and I suppose that you can still hear its beautiful music. This cultural aspect is of utmost importance because it is the only sound of Blackbeard's ship that we can experience in its original totality."

(Blackbeard's Sunken Prize, p. 86-87)

Was this email forwarded to you? Subscribe here!

"Of course there was so much pressure to declare that it was [the Queen Anne's Revenge]," Mark Wilde-Ramsing, former project director, recalled. "[Intersal] wanted the story, so they wanted to move along, and we were trying to be scientific, and getting a lot of pressure from the universities." Roughly two years after discovery, the state reached an agreement with Intersal and their sister organization, the nonprofit Marine Research Institute. While Intersal technically had a right to 75% of coins or precious metals found on the wreck, Reeder said that Masters, wanting to keep all of the artifacts together, readily gave up any rights to the physical treasure. What Masters cared about was the recovery, and eventually continuing the quest for El Salvadore. Per the agreement, Intersal did retain exclusive rights to commercial narratives (written, film, short videos) and to reproduce artifacts for commercial purposes. The Department of Cultural Resources took full responsibility for planning and executing the recovery itself.

In March 1997, North Carolina's Governor Hunt announced the find.

"It looks as if the Graveyard of the Atlantic yielded one of the most exciting and historically significant discoveries ever located along our coast," he announced from Raleigh. "The state of North Carolina is working to protect the site and will do everything we can to that end. We look forward to the day when all North Carolinians can see these exciting artifacts for themselves."

The first several years after discovery were mainly spent exploring the wreck, so state archeologists could decide what to do with it. They mapped out the area, officially named Site 31CR314. After digging trenches to look through the top layer of artifacts, spotting plates and even a small fleck of gold among other items, the archeology team was more assured that the wreck was their pirate ship. (In this context, the ship's name is almost always shortened to QAR, even when said aloud — using the whole thing is like calling a Bob "Robert"; it's usually done for effect or to be proper.)

To proceed, the DNCR needed a lab that could handle a huge wave of artifacts, staff, and a recovery plan. For recovery, there were options: Leave the wreck completely alone (almost unthinkable), monitor and maintain the site, do partial excavations and re-bury the remaining site (more traditional), or — completely unprecedented — recover the entire site. Wilde-Ramsing and a colleague proposed full or nearly complete recovery in 1999. The plan was officially approved in 2004, and after funding came through in 2006, archeologists dove into action at a full tilt.

"It's a shallow wreck," former project videographer Rick Allen described the site. Allen is a producer/director with plenty of dive experience under his belt. "It's only like 24 to 28 feet deep depending on the tide, but it's some of the most challenging diving I've ever done in my life … To describe to people what it's like diving on the Queen Anne's Revenge, I would say to fill your washing machine up with coffee or tea, climb in, and turn it on." Starting at the rear of the ship, they worked towards the bow, which was pointed towards shore when she ran aground. On good — rare — still water days, visibility on the site is about 25 feet. The average was more like three to ten feet, pieces of the wreck coming into focus slowly but somehow also all at once as you moved through the cloudy green-tinged water. For the first few years, Allen's view of the wreck was in two-foot squares that he pieced together in his head. "So I built a map in my head of things, because I would recognize, 'Oh, there's a rigging strap, if I go left, there's a cannon. And if I go up, there's an anchor.' … And so I had this little map in my head based upon these landmarks that were literally a foot or two apart."

Almost every year from 2006 to 2015, a team spent time on the site. Dive seasons averaged at about six weeks in the fall — when the water was still warm, but the wind switched around from its usual summer course (please note that it was better to work during hurricane season than fight the currents with the wind against them). With its wide deck and general horsepower, the Marine Fisheries Division’s R/VShell Point was an ideal base to work from. When the Shell Point was available, divers suited up on her wide deck — wetsuit for a shirt, full mask, tank, and fins. Noting that after suiting up you felt like a penguin out of water, Wilde-Ramsing said that he wore blue jeans to protect his legs from shredding on the barnacle-laden wreck. It was best to work at high tide — low tide tended to bring stronger currents and hazier water. Allen, who conducted his one thousandth dive on the QAR, said the job is a double task load. On one hand there was the ordinary work of documenting any site, and on the other, the task of staying alive and managing risk underwater. Archeologists also managed these dueling priorities, diving with extra equipment like a weight to keep them in place and a piece of waterproof mylar paper attached to a slate for notes.

On the inlet floor, archaeologists worked in 5'x5' units marked off by black-and-white checkered frames. Each square was numbered, and, as federal archaeologist Linda Carnes-McNaughton explained, each artifact pulled from the sand was assigned a unique number that will be linked to it for the rest of its life. One of the recovered gold fragments, for instance, is QAR1143.009. Anyone working on that specific piece in the future should be able to track exactly where it came from, and its context (What was found near it? What conservation work has been done on it? Have any predecessors conducted research related to the piece?).

Anchor recovery day. All images featured in this issue courtesy Amanda Dagnino, NC Coast Collection

Wilde-Ramsing estimates that the QAR wrecked in 12 feet of water, then sank down and settled, like your feet might at the water's edge. It was not a high speed, thunderous crash with men jumping overboard to save their lives — it was likely a standard shallow-water wreck, a grinding halt, the sea's slow but inevitable invasion. Eventually, the ship completely succumbed to the water, to be buried in the seabed and exhumed by the whims of the tide. This means that artifacts are both a few inches and a few feet below the surface, and finding everything the wreck has to offer requires equipment ranging from five gallon buckets to tightly-woven filters. Using dredges (picture a very long, high-powered vacuum hose), the recovery crew brought artifacts and sand alike to the surface to run through a sluice, checking for fragments that are invisible through a scuba mask. Many artifacts retrieved from Site 31CR314 are obscured by a cocoon of concretion, a buildup of corrosion and marine growth. It's heavy, lumpy, and hard as a rock — and after a sometimes years-long process, concretions surrender new surprising artifacts.

During the 2007 season, archeologists recovered concretion QAR1445.000 from Unit 105, towards the center rear of the ship, in the neighborhood of several cannons.

Down on the inlet floor, Wilde-Ramsing said that it was easy to get absorbed in the work, to almost forget that your air was running out. The quiet insulation of being surrounded by water was broken by staticky communication and fish "crackling" nearby. Black sea bass were particularly curious about their work, hovering nearby to inspect. Sea urchins dotted the site, and octopuses also came and went, sometimes hiding out in the dredge and having to be coaxed out before work could begin in the morning. [editor's note: for any pedants out there, we looked it up and are satisfied that using octopi as a plural for octopus is for colloquial, not edited, material] Extended time in the sun and ocean lent the team a waterlogged, deep-toned look. Archeologists tended to alternate between diving and working the sluice on deck - one tank of air bought about an hour's worth of work underwater, and because of the strong currents, one hour at a time was enough. As a break, they'd work above water, then suit up and repeat, averaging four to five dives per day (the record: 28).

Wilde-Ramsing said a good day started with good weather overnight, leaving all of their equipment in its place on the ocean floor, and all of the removed sand staying removed. On a good day such as this, the staff (which ranged from "a handful" to over two dozen people) all knew their tasks, and did them well. It was "efficiency and expectation all rolled up in one, that something may turn up at any time." Bad days involved bad weather, unforgiving currents, divers swept off the wreck and a hundred yards away from the site and once, a capsized boat (no one was on board, and that was early on — they got much more safety-conscious as time went on).

Bringing up a cannon required extra time and coordination. Divers attached the cannon to a bag that would inflate with air and eventually float the gun to the surface on a line towards (but not directly under) the recovery vessel. Wilde-Ramsing said that when a cannon got momentum and surfaced, it looked like a nuclear submarine, and they learned by experience how to bring them up. On one of the early attempts, they were operating from a larger boat, and that larger boat starting pulling away from the site, dragging its mooring block behind it across the seabed.

"Luckily it didn't go across the site, where it had enough energy to rip up the old anchors and cannons."

The next cannon they retrieved, they tried to hook the line directly onto the cannon, not the airbag - the ties slipped, and the cannon (which was supposed to travel horizontally all the way up) turned vertical, rocketing to the surface and yoyoing up and down.

"Luckily the divers were out of the way," Wilde-Ramsing concluded. Even as the team gained more experience, and even without any truly major situations, working on water means unknown factors with a thousand permutations.

"We had a lot of planning, but then you never quite knew what was going to happen."

Along with many other items including cannons, QAR1445.000 migrated to the conservation lab in Greenville, NC. It was still an unknown, an abstract shape cast in solid grit.

The job was not just digging and surfacing, marking locations, settling new artifacts in the temporary storage, and writing up reports. There was also the people element. The public had (has) great interest in this pirate ship, and the recovery team tried to engage as much as possible. When they brought up a cannon, they invited press and special guests — it didn't matter if it was the sixteenth one, Wilde-Ramsing said, a cannon always created a buzz. Afterwards, they'd set the cannon up in a public spot, either in Fort Macon or downtown Beaufort. As curious onlookers lingered, the cannon would pop and crackle as the barnacles attached to it protested their new environment. Over the years, the wreck has been covered by National Geographic, The New York Times, The London Times, Smithsonian Magazine, the BBC, and the Discovery Channel, to name a few. Good Morning America even broadcasted the dig live. The broader the audience, the more reasons higher-ups from the Raleigh office found to be there, readily available to give a quote or make an on-camera appearance.

For education, the DNCR piped live streams from the dive into classrooms; archeologists and historians could speak with students, and answer questions (divers who weren't in the mood to be on camera could easily escape by backing up a few feet to be out of view, hidden by clouds of stirred-up silt).

In the web of interpersonal connections, there were always tuggings of the various interests at play. On one end of the spectrum, there were the treasure hunters, completely earnest but perhaps with some cowboy tendencies — and on the other, ECU with an academic bent towards rigorous ideals, not to mention the state with its own (sometimes wavering) budget and agenda. But beneath the water, all of it — the tourists, the press, the ever-shifting plans and all those who wanted input — could disappear for a while.

Aside: The sternpost, by the way, is marked with a French foot - 12.79 inches, as opposed to the English 12 inches, or the Dutch 10-inch foot. - Watkins-Kenney, Hidden Histories of La Concorde and Queen Anne’s Revenge, p. 204

If someone yelled "Fire!" in your home, what would you grab before dashing out the door? This is how Wilde-Ramsing explains the thought process during a shipwreck. Maybe you'd reach for items with the highest monetary value, hard drives with years of work, a favorite sweater that happened to be draped over the couch, or your grandparent's irreplaceable photo album. A shipwreck has some of the same elements — suddenness, quick evacuation, not being able to guarantee the fate of whatever you leave behind. What remained aboard the Queen Anne's Revenge is telling, and so is what is missing. What is left of the ship herself is pieces of the stern, some of the ribs, and planking.The remains can tell us what Blackbeard and crew would have seen on a daily basis — windows with a greenish sea glass tint and a bull's eye, sails reinforced with special stitching, lead patches (over 100 of them) used to plug up leaks, a small bronze signal gun that would have swiveled on the deck and glinted in the sun.

This is not an exhaustive list, but gives a good snapshot of the mix of traditional and thrown-together weaponry aboard the QAR.

Recovering an entire wreck gives archeologists and historians the chance to study not just the bare bones of what the pirates did and how they fought, but how they actually lived, how they spent their leisure time. They had square gaming chips possibly used to play checkers or sennet, white clay pipes, brass buttons, and a stray shoe buckle monogrammed S.B. (for Stede Bonnet? one analyst mused). Archeologists have also found impressions of strong drink on the ship in fragments of four stemware glasses, one specifically made to commemorate the coronation of George I, and remnants of many bottles, including one intact wine bottle in a shape known as Queen Anne style for its stodgy bottom (yikes).

Medical tools found on the site give us a window into what illnesses impacted the QAR crew and how they were treated. There are ordinary, recognizable pieces like a mortar and pestle or silver needle likely used to stitch up wounds, and less savory artifacts like a urethral syringe (frequently used to treat venereal disease with mercury) and three pump clysters (used to administer enemas).

Shattered animal bones — mostly beef or pork, sometimes fish or foul — give us clues about diet; a couple of bone remains and gnaw marks tell us the pirates had rats scurrying the ship. Even the dishes they ate from carry significance; it matters that of the 25 pewter plates found, five have English maker's marks, and that there was a teapot from the Kangxi dynasty aboard.

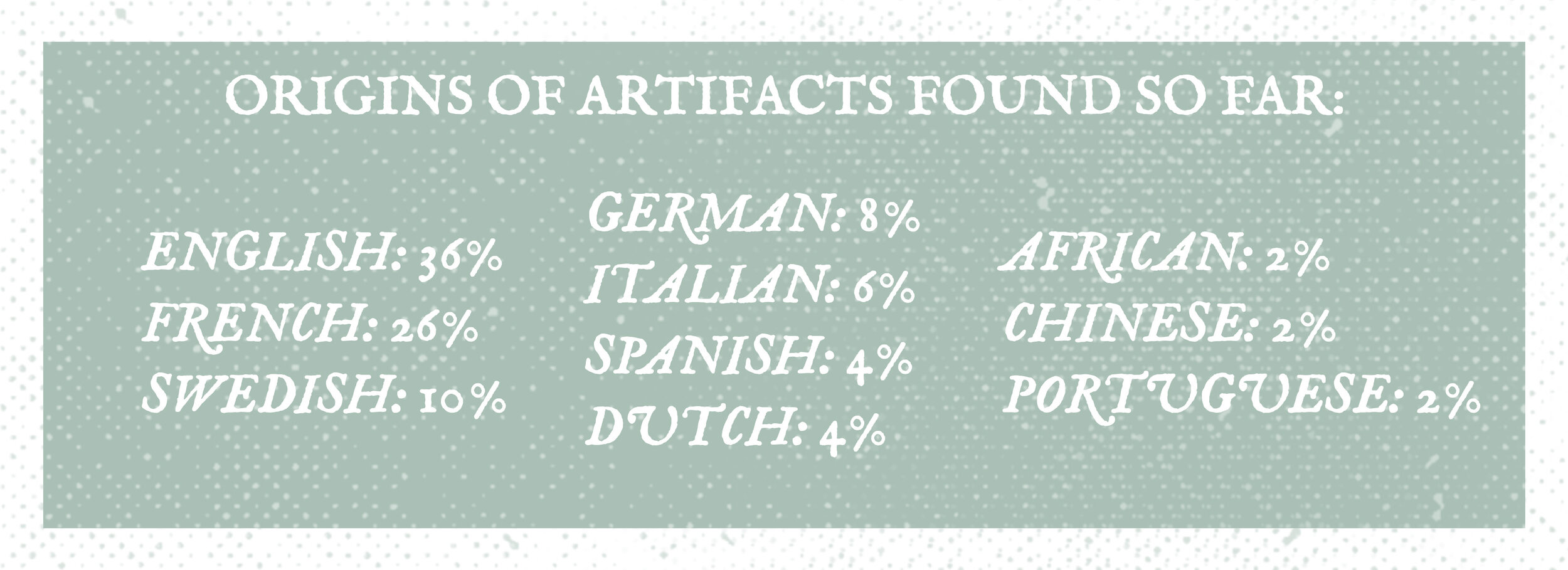

Archeologist Linda Carnes-McNaughton explained that ships plying the Atlantic ought to be viewed as representations of the global market, and an archeologist should always approach new artifacts with an open mind towards their origin. As you would expect of a French ship stolen by men from British colonies, the found artifacts are a mixture of French and English — with a sprinkling of Italian, Spanish, and German origin.

Time in the field only represents about 10% of the work involved in conservation, only the tip of a labor-intensive iceberg; the remaining hours are spent in and around the lab. Most QAR artifacts can't simply be pulled out of the ocean and set out to dry — after 300 years taking on salt in the ocean, they would crumble into dust in a matter of a few days. In the early days, artifacts were stored underwater in makeshift tubs wherever there was room — a storage building here, some extra space at the Carteret Community College's mariculture building there. In 2004 East Carolina University dedicated a permanent lab space, an off-campus group of buildings just outside Greenville, NC.

During normal times, you can visit the lab and take a tour. They open it up for visitors on first Tuesdays (registration required), and also give tours to groups on appointment. More on that here.

X-rays illuminate what Wilde-Ramsing describes as the ghost of an artifact, which conservators work towards by carefully breaking down layers of concretion with a tool called an air scribe — basically a tiny jackhammer with a point the size of a ballpoint pen. When artifacts/concretions aren't being worked on they're kept in desalination baths to gradually remove salt content. The monitored tubs with shallow water that just covers the artifacts give the open warehouse area a vaguely brackish smell, the equipment's dull mechanical rumble and the air scribe's higher pitched drilling echoing off the cement floors.

By December 2009, an x-ray revealed one of the artifacts enveloped in concretion QAR1445.000. Along with a sister artifact in another concretion found nearby, it was "shaped like large beer tankard", later identified as a breech block. Breech-loading cannons saved the time spent ramming powder and shot down the muzzle from the front. Instead, the pirates would have packed gunpowder into a removable breech block, which was inserted into the back of a small swiveling cannon which could be devastating at close range.

A cannon can take six months to remove from its concretion with one person working on it for hours every day, and seven years to complete the desalination process. Fortunately, once an item is recovered from its shell, it can be taken out of water and examined for short stretches of time.

After being removed from its concretion, each artifact gets a new number, an extension of where it is found - the breech block became QAR1445.009.

One of Linda Carnes-McNaughton's first projects was examining a piece of glazed green ceramics (pottery is her specialty; Wilde-Ramsing calls her Jughead, a favor she returns by calling him Bubblehead — all in good fun). The piece was initially identified as English, but Widle-Ramsing wanted a second opinion. Carnes-McNaughton says her favorite tool is her eyes — to examine once, twice, three times — but that it's still a very tactile job. You need to be able to turn the item over, feel the heft of it, study a ragged edge. It's both macro and micro work — she would have a microscope on her table, and toted in a portable library in two or three crates to check the minutia with the larger picture, filling her analysis sheets with drawings to show what the sherds fit in.

After examining the pottery, she began to think it was actually French. So she reached out to experts in Mobile, Alabama and Quebec (both homes to old French settlements). And this is where working on a famous pirate wreck comes in handy — Carnes-McNaughton said that the Queen Anne's Revenge consistently opened doors across the globe. Not only did she receive samples that helped her confirm the pottery was French, experts the world over have been happy to lend a hand — in dendrochronology for analyzing wood samples, geology, study of current patterns and inlet movement, and in identifying French maker's marks.

Numbers pulled from Pieces of Eight: More Archeology of Piracy

In 2016, conservator Erk Farrell opened up the breech block (QAR 1445.009) for cleaning. Through a murky ooze, he noticed fragments of paper — small, none larger than a quarter. Lest you skim past this: He found paper. 300 years submerged in saltwater should have dissolved the scraps long before their discovery, a discovery so shocking, Farrell's first instinct was to swear profusely before calling over a colleague for a second opinion. Allowing paper to dry goes against every instinct of marine archeology (what with the crumbling artifact thing), but after urgent consultations with experts in paper conservation, that is exactly what happened with newly-found artifacts QAR1445.013-1445.028.

For months on end, the book that sourced the pages torn out and stuffed into the breech block remained elusive. The fragments were scattered with flickers of clues in single words or parts of words: South, of San, (f)athom, Hilo, and a single, solitary e. Conservator Kim Kenyon searched every 17th and 18th century she could find that fit the basic profile, sifting through pages for an exact match to their fragments (same letters above, same below, same spacing). Before typing up a report that stated the investigation would have to be ongoing, she decided to double-check a few books — and found the book: Captain Edward Cooke's A Voyage to the South Sea, and Round the World, Perform’d in the Years 1708, 1709, 1710, and 1711. It was the very first edition, and included vivid descriptions of far-off places and adventures on the high seas, including the rescue of Alexander Selkirk (a sailor who survived four years on a maroon island, and whose story would eventually inspire Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe). Although we know from passing accounts that Blackbeard/Bonnet traveled with books ("a good library" per the Boston News-Letter), this is the first archeological evidence for it, the first title that was definitely aboard the Queen Anne's Revenge. And all from a breech block recovered back in 2007.

The items you see in museums represent hours of blood, sweat, and tears (literally, on all fronts), exhausting physical labor and tenacious research combined with time to simply let the artifacts be. Just from 2006 to 2012, archeologists spent over 40 weeks on the site. Former project director John Morris wrote that from the discovery in 1996 through 2015, the QAR team spent 5,301 dives and 4,384 hours exploring the site. And to date they have only recovered about 60% of the wreck (some 400,000 artifacts).

You can view artifacts from the Queen Anne's Revenge for free at a couple of museums: The North Carolina Museum of History in Raleigh (go to the Story of North Carolina exhibit, pass the dugout canoe, and take a left), and the North Carolina Maritime Museum (they have the bulk of recovered items — while you're there, visit the library tucked in the back corner of the museum).

The rest is still in the water, and hopefully still safely under sand. The last pieces are less glamorous (only a few cannons are left to bring up and make a buzz), but excavating the bow area has potential to reveal more about the Queen Anne's Revenge during the many years when she was La Concorde, and about the enslaved people she carried. The first full recovery in the world would provide a useful blueprint for future projects, Wilde-Ramsing said. Rick Allen described a shipwreck as already holding a history, people associated with them.

"The shipwreck is really just the manifestation of that story," he said, and each piece pulled from the wreckage is a handshake with the past. That connection was — is — important. It brought a team of unlikely collaborators together, and beckoned at least 14,000 people who visited the expanded Queen Anne's Revenge exhibit during its opening week, and thousands more after that. The spot in Beaufort Inlet was so meaningful to Intersal president Phil Masters that he had his ashes scattered over the wreck.

But the site is fraying at the edges. 15 hurricanes passed over the site between 1996 and 2005 alone. The situation was urgent back in 2007 when the project's mainstays wrote,

"This invaluable resource is in danger of being lost because of steady sand depletion in the site area … Interdisciplinary research indicates sand loss and erosion will eventually expose all the artifacts buried under protective sand. The greater threat is the catastrophic scour and erosion caused by tropical storm events, especially during this period of heightened activity. One significant hurricane could effectively destroy the archaeological context of the site and cause the loss of countless artifacts." Who knows, maybe some have already been knocked loose, washed ashore, and been taken home by a beach-combing tourist.

So, if the site is important, and people are invested in it, why has there been no artifact recovery since 2015? A good old-fashioned pile of legal trouble.

If you’d like to learn more on your own:

Learn how to free an artifact from concretion using the example of...a chocolate chip cookie.

Read up on the trickiness of conserving organic material, like rope, cloth, or bones. (the whole QAR blog is a treasure trove, so if you're extra-curious about artifact conservation, this is a good place to start)

Watch footage from some of the dives, and see how you think you'd fare on the wreck.

Check out Blackbeard's Sunken Prize for an excellent layman's guide to even the technical aspects of the QAR project.

Have feedback, questions, or flattery?

Feel free to reach out here.

IF YOU’D LIKE TO SUPPORT LONG WAY AROUND, PLEASE CONSIDER

FORWARDING TO A FRIEND WHO WILL ENJOY THE SERIES.

NOTES

series of three divers: Wilde-Ramsing, Mark and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton. Blackbeard's Sunken Prize: The 300-Year Voyage of Queen Anne's Revenge. University of North Carolina Press, 2018. p. 1

1750 while carrying a fabulous load of gold and silver:

state employee pointed him towards a copy of Dave Moore's prospectus: Dohm, Megan. "Preserving a Pirate Ship." Carolina Shore, Fall/Winter 2018.

State archeologists dove the site the day after its discovery: Wilde-Ramsing, Mark and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton. Blackbeard's Sunken Prize: The 300-Year Voyage of Queen Anne's Revenge. University of North Carolina Press, 2018. p.6

So when the divers pulled up a bell: Ibid., p. 6-7

Archeologist Richard Lawrence recounted it: Ibid.

Back at the DCR's underwater archeology hub: Ibid., p. 7

inscription IHS Maria, or Holy Name of Jesus, Mary: Ibid., 86

"It looks as if the Graveyard of the Atlantic yielded": Quoted in QAR Management Plan

officially named Site 31CR314: Morris, John W. "The Site History of 31CR314, Queen Anne's Revenge: A Retrospective Assignment." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 221

Wilde-Ramsing and a colleague proposed full recovery in 1999:

officially approved in 2004: Morris, John W. "The Site History of 31CR314, Queen Anne's Revenge: A Retrospective Assignment." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 226

the bow, which was pointed towards shore: Wilde-Ramsing, Mark U. and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton. "Blackbeard's Queen Anne's Revenge and its French Connection." Pieces of Eight: More Archeology of Piracy, edited by Charles R. Ewen and Russell K. Skrowronek, University Press of Florida, 2016. p. 26

Almost every year from 2006 to 2015: Ibid., 20

and

Morris, John W. "The Site History of 31CR314, Queen Anne's Revenge: A Retrospective Assignment." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 223

Marine Fisheries Division’s: Wilde-Ramsing, Mark U. and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton. Blackbeard's Sunken Prize: The 300-Year Voyage of Queen Anne's Revenge. University of North Carolina Press, 2018. p. 58

was not a high speed, thunderous crash: Wilde-Ramsing, Mark U. and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton. Blackbeard's Sunken Prize: The 300-Year Voyage of Queen Anne's Revenge. University of North Carolina Press, 2018. p. 158

buried in the seabed and exhumed: Ibid., 44-45

artifacts are both a few inches and a few feet: Interview with Mark Wilde-Ramsing

recovered concretion QAR1445.000 from Unit 105: Farrell et al. "Message in a Breech Block: A Fragmentary Printed Text Recovered from Queen Anne's Revenge." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 222

"a handful": Wilde-Ramsing, Mark U. and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton. Blackbeard's Sunken Prize: The 300-Year Voyage of Queen Anne's Revenge. University of North Carolina Press, 2018. p. 59

dragging its mooring block behind it across the seabed:

pieces of the stern, some of the ribs, and planking: Ibid., 90

windows with a greenish sea glass tint and a bull's eye: Ibid., 93

sails reinforced by special stitching: Ibid., 92

lead patches (over 100: Ibid., 94

a small bronze signal gun: Ibid., 100

used to play checkers or sennet: Ibid., 139

white clay pipes: Ibid., 139

S.B. (for Stede Bonnet?: Ibid., 16

fragments of four stemware glasses: Ibid., 136

remnants of many bottles: Ibid., 137

silver needle likely used to stitch up wounds: Ibid., 127

mostly beef or pork, sometimes fish or foul: Ibid., 128

gnaw marks: Wilde-Ramsing, Mark U. and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton. Blackbeard's Sunken Prize: The 300-Year Voyage of Queen Anne's Revenge. University of North Carolina Press, 2018. p. 129

25 pewter plates found, five have English maker's marks: Ibid., 135

teapot from the Kangxi dynasty: Ibid., 133

buildup of corrosion and marine growth: Wilde-Ramsing, Mark U. and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton. "Blackbeard's Queen Anne's Revenge and its French Connection." Pieces of Eight: More Archeology of Piracy, edited by Charles R. Ewen and Russell K. Skrowronek, University Press of Florida, 2016. p. 22

basically a tiny jackhammer: Dohm, Megan. "Preserving a Pirate Ship." Carolina Shore, Fall/Winter 2018.

after 300 years in the ocean, they would crumble into dust in a matter of a few days: Dohm, Megan. "Preserving a Pirate Ship." Carolina Shore, Fall/Winter 2018.

vaguely brackish smell: Dohm, Megan. "Preserving a Pirate Ship." Carolina Shore, Fall/Winter 2018.

"shaped like large beer tankard":

packed gunpowder into a removable:

A cannon can take six months: Dohm, Megan. "Preserving a Pirate Ship." Carolina Shore, Fall/Winter 2018.

seven years to complete the desalination process: Ibid.

QAR1445.009: Farrell et al. "Message in a Breech Block: A Fragmentary Printed Text Recovered from Queen Anne's Revenge." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 222

taken out of water for short spells: Wilde-Ramsing, Mark U. and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton. Blackbeard's Sunken Prize: The 300-Year Voyage of Queen Anne's Revenge. University of North Carolina Press, 2018. p. 88

dendrochronology for analyzing wood samples, geology, study of current patterns and inlet movement, and in identifying French maker's marks: Interview with Linda Carnes-McNaughton and interview with Mark Wilde-Ramsing

In 2016, conservator Erk Farrell opened:

a quarter: Dohm, Megan. "Preserving a Pirate Ship." Carolina Shore, Fall/Winter 2018.

Farrell's first instinct: Ibid.

after urgent consultations with experts: Ibid.

QAR1445.013-1445.028: Farrell et al. "Message in a Breech Block: A Fragmentary Printed Text Recovered from Queen Anne's Revenge." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 233

South, of San, (f)athom, Hilo: Ibid., 233-234

Conservator Kim Kenyon searched: Dohm, Megan. "Preserving a Pirate Ship." Carolina Shore, Fall/Winter 2018.

the book: Captain Edward Cooke's: Farrell et al. "Message in a Breech Block: A Fragmentary Printed Text Recovered from Queen Anne's Revenge." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 239

very first edition: Ibid.

over 40 weeks on the site: Wilde-Ramsing, Mark U. and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton. "Blackbeard's Queen Anne's Revenge and its French Connection." Pieces of Eight: More Archeology of Piracy, edited by Charles R. Ewen and Russell K. Skrowronek, University Press of Florida, 2016. p. 5

1996 through 2015, the QAR team spent 5,301 dives and 4, 384 hours: Morris, John W. "The Site History of 31CR314, Queen Anne's Revenge: A Retrospective Assignment." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 222

400,000 artifacts: Wilde-Ramsing, Mark U. and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton. Blackbeard's Sunken Prize: The 300-Year Voyage of Queen Anne's Revenge. University of North Carolina Press, 2018. p. 190

15 hurricanes: Wilde-Ramsing, Mark U. and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton. Blackbeard's Sunken Prize: The 300-Year Voyage of Queen Anne's Revenge. University of North Carolina Press, 2018. p. 58

"This invaluable resource is in danger":

Weapons Graphic:

24 cannons Wilde-Ramsing, Mark U. and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton. Blackbeard's Sunken Prize: The 300-Year Voyage of Queen Anne's Revenge. University of North Carolina Press, 2018. p.106

Ornate dagger handle: Ibid., 114

Sandstone grinding wheel, for sharpening blades: Ibid.,116

250,000 small caliber lead shot (concentrated in the stern, indicating that’s where the magazine was: Ibid., 119

22 grenades, cast-iron shell: Ibid.,120

Langrage: Ibid.,105

and

Pieces of Eight, "Blackbeard's Queen Anne's Revenge and its French Connection." Pieces of Eight: More Archeology of Piracy, edited by Charles R. Ewen and Russell K. Skrowronek, University Press of Florida, 2016. p. 34

Cannonballs and bar shot: Wilde-Ramsing, Mark U. and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton. Blackbeard's Sunken Prize: The 300-Year Voyage of Queen Anne's Revenge. University of North Carolina Press, 2018. p. 108