ISSUE № 6: LEGAL TROUBLE

LEGAL TROUBLE

Illustration by Kelsey Martin of Kettle Pot Paper

A couple of notes before we get going: As always, with older quotes we have updated spelling and punctuation for clarity. Also for clarity, the Department of Cultural Resources (DCR) eventually became the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources (DNCR) — to save us all the headache, we will be referring to the department by its original title throughout the body of this article.

December 1718

On the day after Christmas, five men broke into the home of North Carolina deputy secretary John Lovick. The men were not unknowns, bursting blindly into a faceless government official's space; it was a wide frontier, but a small town. Edward Moseley and Maurice Moore, brothers-in-law and lawyers, played ringleaders in the break-in. Weeks earlier, they had guided Captain Ellis Brand across the sound in hopes of catching Blackbeard at home. It's also highly likely that these two were in the group that asked Virginia's Governor Spotswood to intervene with the pirate situation — Captain Brand wrote that the two of them had been "much abused by Thach" in late October; one can only imagine they were more than happy to assist in his capture. After Thatch's last November battle at Ocracoke, members of the British Navy joined Captain Brand in Bath to round up the remnants of his crew and evidence for trial in Virginia.

Another colony sending outside forces to settle the piracy matter, apparently at the behest of local Bath men, was alarming to Governor Eden (after all, a few decades earlier, charges of being too chummy with pirates successfully ousted a South Carolina governor). We don't have Eden's letter to proprietary man and Carolina establishment mainstay Thomas Pollock, but we do have Pollock's response; the urgent tone indicates a certain amount of scrambling to get things in order. Pollock wrote that he was completely in the dark about the expedition to seek help from authorities in Virginia until Captain Brand arrived in Bath, and warned that, "There seems to be a great deal of malice and design in their management of this affair." Pollock prudently urged the governor to cooperate and allow the pirates' trial in Virginia to keep the stink of the matter away from North Carolina's government.

An aside: Lovick later married Governor Eden's step-daughter Penelope. Unrelatedly but of interest to aside readers, I remember hearing a story at Tryon Palace about the governor's daughter, Penelope, trying to escape out the window to elope with Blackbeard. One of many rousing (but untrue) tales.

The strategy did not work. The odor of corruption — whether real or imagined — hovered over Bath. Convinced that they would find evidence of the government's connection to Blackbeard on paper, the five broke into John Lovick's house, nailed the door shut behind them, and searched the government records and journals stored there for 20 hours. Spearheaded by Edward Moseley (who fell squarely on the rebellion side of Cary's Rebellion and opposing Pollock's sort), in some ways, the men confirmed Pollock's suspicions. They rifled through Lovick's home for proof of wrongdoing that could also function as political ammunition.

September 1998

Like most conflicts, matters between Intersal (the salvage and recovery company who discovered the Queen Anne's Revenge), Nautilus (the site's video crew), and the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources didn't start with rivalry or sides. It started small and friendly, a group of (perhaps unlikely) collaborators pulling together to bring up a shipwreck. No one would have imagined that the relationship would eventually have a strand that ran all the way to the Supreme Court. Almost two years after discovery, Intersal, MRI (a nonprofit Intersal set up to help with recovery efforts), and the Department came together with a memorandum of agreement. The agreement started out by acknowledging that the QAR was "of inestimable historical and archeological value" and establishing that all of the artifacts would remain together, ultimately landing in a museum, where the public could enjoy them. The DCR, MRI, and Intersal planned to be partners in recovering the Queen Anne's Revenge for the life of the agreement, which lasted through 2013, with an option for Intersal to renew for another ten years.

New here? Find all the past issues here.

Then came the nuts and bolts sections, definitions and divvying up responsibilities and rights. While Intersal and MRI were part of an advisory committee for the project, the DCR was ultimately responsible for the wreck and had the final say. While the state retained the right to make non-commercial educational material, Intersal received all rights to crafting commercial narratives (film, written, etc.) and to make limited edition, museum-quality artifact reproductions. MRI and the DCR shared an exclusive right to tour artifacts (during the bulk of QAR recovery work, artifacts from Black Sam Bellamy's Whydah toured museums in a smash hit exhibit that many wanted to replicate). Current Intersal president Dave Reeder said that Intersal's late founder, Phil Masters, had a grand scheme for making a full size Queen Anne's Revenge reproduction and parking it near a pirate village, a small slice of living history on the water in Beaufort.

The relationship was framed in collaboration, Intersal, MRI, and the DCR sharing information, advice, and documentation of the site. Perhaps most importantly to Masters, the state agreed to accept Intersal's work on the QAR Project towards meeting performance requirements necessary to renew his search permit for El Salvadore — a treasure hunter's dream project, purportedly loaded with legendary amounts of precious metals when it sank in Carolina waters — for the life of the agreement. As long as the state had no just cause for terminating the permit, they saw Intersal searching the waters as a benefit. Also in 1998, Nautilus Productions/Rick Allen became the project's official video crew through an agreement with Intersal. Years into documenting the site, Allen officially agreed to share his footage for research purposes, free of cost. Per an agreement with the Underwater Archeology Branch (an extension of the DCR), the footage was not for broadcast or display without written consent.

For years, the many moving pieces of the Queen Anne's Revenge Project, the separate and diverging interests almost always eventually came together for the sake of preserving the wreck. Intersal loaned out equipment, knowledge, and time, volunteers invested time in the project, and the DCR dedicated precious resources to the work. In 2006, the dig started in earnest, and Allen spent weeks documenting the spring and fall dives. In 2010, the QAR Project worked to shift public education into the new digital age, exploring engaging with the public through blogs and video footage. Allen wrote to then-state archeologist Steve Clagett that while he supported outreach, he was concerned that posting clips could make video easy for outside filmmakers to poach and use without paying any royalties. After presenting several examples of video snatched from the internet by contractors working for companies as large as the Discovery and History Channels, Allen proposed several solutions in addition to a classic watermark: Hosting the video on the DCR's site rather than YouTube or Facebook, limiting the size of the video, and overlaying it with a graphic in a spot too prominent to crop out.

Jumping ahead two years, to autumn 2012 — the QAR Project had recovered thousands of artifacts, and still had a long way to go. Intersal's lawyer wrote the DCR to renew the Memorandum of Agreement, noting that MRI was also ready to extend the agreement to 2023. Over late 2012-early 2013 the DCR saw a changing of the guard; in addition to the project's long time director Mark Wilde-Ramsing's retirement, the department's secretary and deputy secretary also changed over. In 2012 the state started directing hundreds of thousands of dollars from private donors/corporations to the Friends of Queen Anne's Revenge (a nonprofit with strong ties to the DCR). Wilde-Ramsing, who was on the Friends founding board of directors in 2008, said that the group was initially intended to function more as a centre for coordinating efforts and funding with the many invested parties — the state, Intersal, MRI, East Carolina University, and the museums or historic sites that might serve as the landing place for the artifacts after conservation. It is not uncommon for a site under the DCR's umbrella to have a "Friends of" group (i.e. Friends of Fort Dobbs or Friends of the Alamance Battleground). They help with fundraising, general support, and even provide educational aids for school groups. Compared with a large sample of current "Friends" groups, Friends of Queen Anne's Revenge had an unusually high proportion of DCR employees and former employees on its board of directors during its early years.

In early 2013, the QAR Project and Underwater Archeology Branch's new director John "Billy Ray" Morris officially joined the Friends Board of Directors as treasurer (Mr. Morris declined to comment for this article). At the April 22, 2013 Friends of Queen Anne's Revenge board meeting, Morris proposed bringing in two outside production companies to make a new educational web series.

On May 10, just weeks before the spring dive, Allen received a call from an Underwater Archeology Branch staff member alerting him to an independent film crew being brought on to the project. Allen called Steve Claggett, who confirmed that the crew was coming — and Intersal did not know yet (Mr. Claggett could not be reached for comment). Right before the spring dive, department secretary Susan Kluttz wrote Intersal that although the department was grateful for Intersal's work and hoped they could work together on educating the public, "After carefully reviewing the Agreement and weighing its benefits against the current and future needs of the Department, I have concluded that it is not in the Department's best interests to renew the Agreement." Signing off, Kluttz wished Intersal well in their future endeavors.

All of this set the scene for the 2013 spring expedition, where choppy weather also made cannon recovery more difficult than anticipated.

"I'm a professional," said Rick Allen, owner of Intersal's video designee Nautilus Productions, "So I did my job. But it was…what's a good way to put it? It was a really interesting dynamic on the boat." Part of the way through the expedition, WRAL reported that the project was in danger of running out of funding.

Wilde-Ramsing and board president Richard Lawrence resigned from the Friends of Queen Anne's Revenge Board Of Directors, in part over concerns about how Allen was treated (another factor was the pivot to more active fundraising). In his resignation letter, Lawrence wrote,

"For fifteen years, Mr. Allen has provided countless hours and indispensable expertise, assistance, and support for the QAR project, mostly at his own expense … When the current QAR documentary effort was proposed by Think Out Loud Productions and Wildlife Productions, we were told that Rick Allen would be a part of the documentary process. This apparently was not the case, and I regret any role that I and the FoQAR board had in creating this disagreement with Mr. Allen. I urge the Department of Cultural Resources to work with Mr. Allen to find a fair and amicable resolution to this dispute. Rick has worked too long and hard for the QAR project for our relationship with him to end in this manner.”

Shortly after the 2013 spring dive, Intersal filed a petition for a contested case hearing.

May 1719

Despite a lack of evidence that Governor Eden directly profited from engaging with the pirates, the crew's Virginia trial yielded worrying results. The compass pointed to Tobias Knight: Vestryman, Chief Justice, secretary, and sickly man in his mid-sixties with a home at the mouth of Bath Creek. In May, the governor's council gathered in the home of Frederick Jones to hear the evidence and Knight's defense.

In Virginia, four men (Richard Stiles, James "Jemmy" Blake, James White, and Thomas Gates) testified that after they helped Blackbeard capture the Rose Emelye, Blackbeard left the French ship and most of the crew in Ocracoke Inlet while the four carried Thatch and some of the booty inland in a smaller boat. In the wee hours of the night, the pirates arrived at Tobias Knight's property — the four crew members unloaded three or four kegs of sweetmeats (sugary food or fruit in the candy/confectionery family), loaf sugar, a bag of chocolate, and several boxes (contents unknown). According to their testimony, Thatch was in the house with Knight until about an hour before dawn, when the pirates all left. On their way out of the Bath area, the men said Blackbeard leapt aboard a small boat they encountered, demanded strong drink, got into a fight, and robbed the small crew of cash, a case of pipes, a cask of strong drink, linen, and other various and sundry items before continuing to Ocracoke.

The testimony of the boat's owner, William Bell, corroborated the pirates' story and placed the date at September 14th, 1718 — a colorful detail that certainly fits with what we know about Thatch's blustery speech patterns is that when Bell asked his assailant who he was and where he came from, "Thache replied he came from Hell and he would carry him [there] presently". Bell had also claimed that Thatch beat him with a sword which snapped, and presented a broken piece of a broken sword on the spot. The timing of this robbery, and Blackbeard's trip inland, was integral to the case. If Bell and the four pirates were telling the truth, and if, shortly after Blackbeard dropped off expensive goods under cover of darkness, government officials accepted without question the pirate's story about finding a laden French ship floating free, the matter would smack of bribery.

The evidence didn't stop with the testimony of four pirates and one man who was robbed in the dark; an essential piece was a letter written in Knight's own hand, dated five days before Lieutenant Maynard caught Blackbeard near Ocracoke, and found aboard the Adventure (Blackbeard's last flagship):

"My Friend: If this finds you yet in harbor I would have you make the best of your way up as soon as possible your affairs will let you. I have something more to say to you than at present I can write, the bearer will tell you the end of our Indian War, and Ganet can tell you in part what I have to say to you, so refer you in some measure to him. I really think these three men are heartily sorry at their difference with you, and will be very willing to ask your pardon. If I may advise, be friends again, it's better than a falling out among yourselves. I expect the governor this night or tomorrow, who I believe would be likewise glad to see you before you go. I have no time to add save my hearty respects to you, and am your real friend and servant, T. Knight"

The evidence against Knight marched on. Captain Ellis Brand, commissioned by Virginia's Governor Spotswood to go with Lieutenant Maynard to bring order to North Carolina, said that he had heard Knight was potentially harboring stolen goods for Thatch. When asked about the goods, Knight vehemently denied any such items were on his property. Captain Brand said that when he returned the next day he "urged the matter home" to Knight. After Brand told Knight that the navy had evidence of the goods through the men who helped deliver them and by a memorandum in Thatch's pocket book, Knight caved and "owned the whole matter". Brand found barrels of sugar in Knight's barn, covered up in hay.

Knight came out swinging in his own defense. He was sure he could make it evident he was "not in any wise howsoever guilty of the least of those crimes which are so slyly, maliciously, and falsely suggested and insinuated against him by the said pretended evidence." For one thing, Knight argued that "Hesikia" Hands' evidence should not be considered, since he was not part of the group that allegedly went to Bath on a bribery junket but was holding down the fort on the Adventure. (He meant Blackbeard's coconspirator Israel Hands, but continues a humorous trend of struggling with the man's name — another source referred to him as Basilica.) In addition to being 30 leagues away from the events in question, Knight pointed out that Hands was giving evidence while "kept in prison under the terrors of death, a most severe prosecution". Knight used this same line of reasoning against the four crew members who said they brought Thatch inland for the meeting, but it wasn't his chief argument: These four were enslaved Black men, and as such could not give evidence that held any legal weight against a white man. There was no chance at cross-examining the four because they were dead, already executed for piracy.

As for Bell, the boat-owner who was accosted early on the morning of September 14, he appeared to be an unreliable witness. After the mugging, Bell made his way to Knight's home, and Knight, in his capacity as justice, interviewed Bell about the robbery. According to a man living in Knight's home, Edmund Chamberlain, Bell initially pointed his finger at Thomas Undey, "Fightery Dick" Snelling, and two other accomplices, and changed his tune to Blackbeard later. Chamberlain also testified that Thatch had not visited the Knight property that September night, and that the pirate could not have snuck into the house much less held a meeting with Knight without alerting him.

Knight's response to the letter and to Captain Brand's recollections are less convincing. In the same breath as owning up to writing the letter to Thatch at Governor Eden's request, Knight denied any ill intent. As to the sugar in the barn, Knight said that Captain Brand did not even have to ask about the goods in storage, that he (Knight) brought up the sugar and explained that it was stored on his property per Thatch's request until a better place could be found for it. Knight said that he told Brand that "every lock in his house should be opened to him" and that Brand found him to be nothing but cooperative. This account directly contradicts a letter Brand wrote to his superiors, where he reported that Knight had been nothing but a roadblock, "advising the governor not to assist me, and he constantly assisting the pirates."

Knight ended his defense by stating that he was not connected to Thatch by business or society — being ill and at times bedridden, he never left his own property. The tall, bearded man came out to the Knight plantation on business with Knight as the secretary or customs officer. To the best of Knight's knowledge, Knight said neither he nor his family had business dealings with active pirates (His housemate Chamberlain's testimony added that Knight had received one gift from the pirates, a gun worth about forty shillings).

October 2013

The end point for Intersal's first wave of legal action (which challenged the DCR's rejection of renewing their agreement and alleged that there was a "pattern of neglect and delay" around the El Salvadore permits, amongst concerns that the new educational web series strayed into narrative territory) was a negotiated settlement agreement. The comradery of the original agreement had evaporated; in the nature of most settlements, they were reaching a point that all parties could live with in order to move forward. Right off the bat, the settlement stated that — with the same conditions as the MOA — the El Salvadore permits were secure through the end of the QAR Project. To clarify media rights, the DCR agreed to only put non-commercial media on their site, to return all archival footage that was missing a watermark or timestamp, and that any media posted going forward would be overlayed with a timestamp and watermark. The department also agreed to pay Nautilus $15,000 by the end of January (the payment arrived a few days into February after prompting from Allen's lawyer; Allen accepted it without any late fees).

In a key shift, both the DCR and Intersal had the right to make artifact reproductions, and they didn't all have to be limited editions crafted up to museum standards. Translation: Gift shop offerings were on the menu. To avoid competition, each party would pick artifacts, alternating picks until they reached 10 total. The business panel would be five people, one representative each from Intersal, Nautilus, the DCR, the Department of Commerce, and one independent academic; the panel was responsible for approving the various plans for making and marketing souvenirs or reproductions.

The first meeting of the business panel was also its last. First, there was the matter of picking the independent historian, who (as the fifth vote) was expected to effectively be the tie-breaker on deadlocked decisions. Intersal brought forward several options — the state rejected them all. Intersal president David Reeder remembers proceeding to picking artifacts for purely informational purposes, since nothing could officially happen without the fifth member of the panel. Intersal picked first — as they agreed in the settlement, their first pick was a sword handle. The state picked next. On the third round of picks, when Intersal floated the idea of a 3D model of the Queen Anne's Revenge, the meeting abruptly shut down. And that was the last of it. Without the business panel, no one could make reproductions. The parties floated into uncomfortable stalemate.

On June 21, 2014, Intersal found out that the DCR had posted footage of the wreck on its Flickr and Facebook pages — they also found media on various accounts held by the Friends of Queen Anne's Revenge and the North Carolina Maritime Museum. The media was not watermarked. In a letter to then-DCR secretary Susan Kluttz and North Carolina's deputy attorney general, Intersal stated that they documented over 2,000 individual violations across the internet. This led to two separate lawsuits — one in state court from Intersal, and another in federal court from Nautilus and its owner, Rick Allen.

October, 1719

The general court session that handled the Lovick house break-in also combed through more ordinary charges: Sabbath breaking, purposefully mismarking hog's ears, cohabitation, a combined charge of adultery and blasphemous words, and someone not keeping their portion of the road in good condition (several charges were on evidence from two different Bells — the historical record is unclear on whether this was vigilance or common snitchery). Four of the five men who broke into Lovick's home heard the evidence against them, Maurice Moore and Edward Moseley (brothers-in-law, both lawyers, ringleaders), Thomas Luten, Jr. (lawyer), and Henry Clayton. Their indictment read:

"With force and armies … [they] did unlawfully enter the said house, fasten and nail up [and keep] the said John Lovick from the possession of the said house." The house was not only the district's naval office, it also contained the colony's seal and important government documents. All four men pleaded not guilty.

Edward Moseley also faced another charge: Seditious speech. Furious at his arrest, he had said to a group of people,

"[the government] could easily procure armed men to come and disturb quiet and honest men, but could not raise them to destroy Thatch, but instead [Thatch] was suffered to go on in his villanies. My commitment [imprisonment] is illegal. It is like the commands of a German prince. I hope to see the governor who has so illegally committed me to a prisoner himself put in irons and sent home to answer [for] what he has done here. And I will endeavor to blacken his character as much as is in my power." Between the unstable colony environment and a king who was imported from Germany and called The Pretender by his opponents, Moseley's words treaded dangerous water.

August 18, 2015

When Governor Pat McCrory signed HB 184 into law, it's unlikely he realized the can of worms his pen opened. In February of that year, Intersal filed another petition for a contested case hearing seeking $14 million from the state for settlement violations, dropped it, then refiled in July, moving the case from administrative hearings to general court. Just days before Intersal officially filed its new suit, part of HB 184 was amended to include a section on media rights, declaring that any media featuring abandoned vessels or shipwrecks turned over to the state would become public record. As public record, outside limitations on how the Department used their media would not apply. When the state submitted its response to Intersal's complaint they argued that, as interpreted by Intersal, the media/narrative sections of the settlement were "void, illegal, and unenforceable" because it violated public policy — public policy which could in part be found in HB 184.

Correlation certainly isn't causation — but it just as certainly seems more like causation when one of the state senators who introduced the amendment in question tells the Associated Press that he added the language addressing the public use of media at the Department's request, and that he is sure the amendment was "brought forth" by the Intersal lawsuit (the July report also included a statement from the DCR which said that the law would not apply to current contracts). Nautilus and Intersal started referring to HB 184 as "Blackbeard's Law", and it stuck. In November, Intersal amended their complaint against department secretary Susan Kluttz, the DCR, and the state of North Carolina. In the complaint, Intersal stated they believed damages to be about $8.6 million. Their allegations revolved around breach of contract and included a true punch in the gut — Intersal believed that, acting on behalf of the DCR, the Office of State Archeology set new unpalatable terms and almost unattainable standards for the search permit for El Salvadore. By the end of the following January, the Department had denied Intersal's attempts to renew its search permit, citing concern for Spain's potential ownership over the wreck and Intersal's failure to meet laboratory and reporting standards.

In December 2015, Nautilus and Allen also filed a suit, this one in federal court, against the governor, Secretary Kluttz, various high-ranking figures in the DCR, North Carolina Senators Davis and Sanderson (who introduced the amended language of Blackbeard's Law), the DCR itself, the state of North Carolina, and the Friends of Queen Anne's Revenge. In March 2016, the Friends of Queen Anne's Revenge officially started the process of dissolution.

All of this information sourced with the Office of US Attorneys, in an explainer that does the system much more justice.

Judge Terrence Boyle of North Carolina's Eastern District heard Nautilus' case. In his complaint, Allen alleged that DCR employees and the North Carolina senate participated in a civil conspiracy to defend the DCR's free use of Nautilus' footage (about 80 hours of it, Allen estimated), effectively rendering it public property. The way Allen's legal team laid it out, department leadership and some in the archaeology branch knew the terms of the 2013 settlement, had the ability and opportunity to enforce them, and did not. Allen sought several results: Blackbeard's Law being declared void and unenforceable, an injunction preventing its enforcement, and damages — times three (or, at least a big enough number to make the state think twice about copyright violation). The state returned with a motion to dismiss the case, arguing in part that its officers were immune to suits in federal court under the U.S. Constitution's Eleventh Amendment. From this point forward, arguments from both sides became less about the merits and facts of the case, but about sovereign immunity and how Congress makes copyright law.

Just in case you haven’t brushed up on your Eleventh Amendment recently; full article available here.

Judge Boyle's order, published March 23, 2017, spent nine pages critiquing how the state apparently took advantage of a constitutional loophole:

"The founders envisioned and wrote a Constitution founded upon the sovereignty of the people, not the states … Just as King George III lost sovereign authority when he transgressed the inalienable rights of the colonists, neither can any organ of government maintain its sovereign immunity when it acts in violation of the Constitution."

After making his thoughts on Eleventh Amendment interpretation clear, Boyle noted that he was constrained by precedent. He also commented that the First Amendment protects lobbying for certain laws (a right, he wrote, that is not contingent on pure intent). On those grounds, three out of five charges were dismissed. Charges related to copyright infringement remained against the defendants.

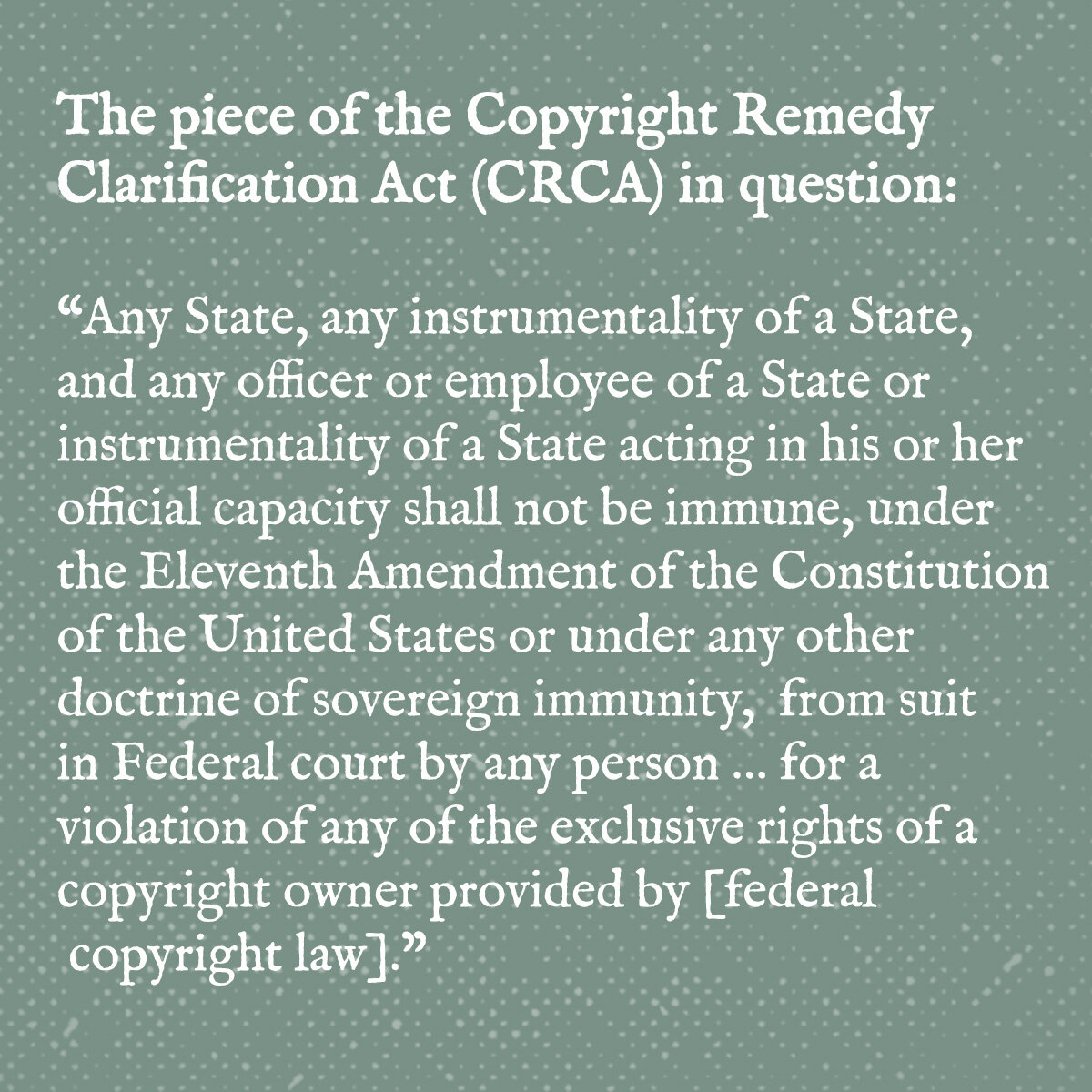

About a year later, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed Judge Boyle's findings, issuing an opinion that reads like a bucket of ice water over his flamethrower pages on the Eleventh Amendment. The Fourth Circuit panel ordered the claims against all of the defendants in their individual capacities dismissed with prejudice (a final call that can't be relitigated), and the claims against the defendants in their official capacities dismissed without prejudice. A key question for both Judge Boyle and the fourth circuit judges was whether or not Congress went about passing the Copyright Remedy Clarification Act (or CRCA, which stated that a state or its agents could not be immune to suits for copyright violations) the right way.

For Congress to pass a law that broached the Eleventh Amendment, it needed to show it was addressing a clearly established problem — Judge Boyle seeing the problem, the court wrote, was not what the law required. With nowhere to go but up, Allen and company filed a writ with the Supreme Court, hoping they'd take up the case.

May 1719

After what appears to be same-day deliberation, the governor's council found the evidence against Tobias Knight "false and malicious", and since "he hath behaved himself in that and all other affairs wherein he hath been interested as becomes a good and faithful officer", the council acquitted him of all charges. And then they moved back to regular council business, settling a will dispute. Tobias Knight died two weeks after the investigation concluded — probably of longstanding illness, but legend says he died of shame.

November 5, 2019

On the day the Supreme Court heard Allen's case, his friends and supporters waited outside the court with pirate flags flapping in the breeze. Each side had 30 minutes to lay out their case while fielding questions from justices (questions which could come at any point and do not extend your allotted time). When lawyers Derek Shaffer and Ryan Park approached the lectern, both faced the intimidating challenge of arguing before the Supreme Court for the very first time. Park, who represented the state, later wrote in The Atlantic,

"As I waited for my turn to speak, I was more nervous than I had ever been, uncertain whether I had what it took to meet the moment."

An aside: The friezes were designed in the 1930s, and the breadth of selected lawgivers is of interest. Other lawmakers included are Augustus Caesar, Menes, Draco, Justinian, Charlamagne, and a rare depiction of Muhammad. (yes, I am available to give tours whenever called upon. Step this way, and we'll take a look at a truly intriguing example of Greco-Roman architecture)

Allen said that hearing your case argued in the Supreme Court is surreal; after getting tickets to your own case, you may have to sit through whatever else is on the docket (on this day, a case regarding maritime liability). There are about 80-90 seats in the court filled mostly by lawyers, and a careful etiquette rules the room. The justices sit on a dais raised to about shoulder height, heavy red curtains behind them. Marble friezes of the great lawmakers — from Moses to Hammurabi, Confucius and Napoleon to Chief Justice John Marshall — look down on the room. Allen described it as "church on steroids." Was it difficult to keep a poker face during the arguments?

"Oh my goodness yes, because the justices are asking questions that you've wanted to ask for years, and you really want to jump up and go, 'Yes! That's what I want to know!' and you can't. It's hard to maintain your composure, especially because it really is very personal. Because it is you that they're talking about, and these are nine people that you read about in the papers, and make decisions that affect the entire United States, not just this year, but for decades to come, and there they are, not that very far away from you."

The petitioner goes first; Allen's attorney, Derek Shaffer, summed up the core of their argument in his opening sentence.

"When states infringe the exclusive federal rights that Congress is charged with securing, Congress can make states pay for doing so." And they were off to the races. Nautilus' argument skated on two cases: Florida Prepaid Postsecondary Education Expense Board v. College Savings Bank and Central Virginia Community College v. Katz. Florida Prepaid addressed how Congress could abrogate (or broach) Eleventh Amendment immunity. The Florida Prepaid decision was potentially undermined when the court later ruled that the precedent it was based on included opinion that overstepped the limits of the case, and therefore not legally binding. Katz was a more recent decision where the court held that Congress rightly abrogated state sovereign immunity for bankruptcy cases using the power bestowed by Article I of the Constitution — potentially cracking the door open for other exceptions. Questions came at each justice's pace (Breyer's slow and deliberate, Sotomayor's in focused probes), and both lawyers made their answers as quick and respectful as possible, trying to circle back to their argument.

Was Shaffer asking them to overrule Florida Prepaid, and upset the apple cart of precedent? Shaffer said it was more like he was asking the court to follow the direction set by Katz.

Would a decision in Allen's favor affect patent law? Maybe.

Was Shaffer arguing that every infringement by a government entity is a constitutional violation? Yes, “pretty much every time”.

Why was the Copyright Remedy Clarification Act based on only 16 cases of state copyright infringement? Does that, Justice Alito asked, seem like enough of a problem for Congress to address? The 16 cases were representative of a larger problem, Shaffer said, only the tip of the iceberg in 1988 — and Congress does have a right to act preventatively. Another reason, he said, for so few cases is that with copyright infringement was that copyright holders are small fish with little incentive to sue a government entity with deep pockets.

North Carolina's then-Deputy Solicitor General Ryan Park argued the state's case, which was much simpler: Sovereign immunity is foundational to the Constitution's structure and the relationship between federal and state governments, and the court merely needed to follow precedent, continuing to shield the states from private suits seeking money for damages. A ruling in North Carolina's favor would protect the states from the high penalties required by the CRCA.

Justice Breyer interrupted with a hypothetical. Suppose a state comes up with a grand new fundraising plan: They'll show Rocky, Mrs. Marvel (he fumbled around for a moment, as if searching his pockets for pop culture references to produce), Spiderman, and Groundhog Day, all in one evening. Quiet Methodist laughter dappled the court. What, Justice Breyer asked, would stop states from streaming these movies for $5 a pop, and then simply accepting a slap on the wrist in the form of an injunction?

Park admitted that there would be difficult cases, and said that a plaintiff could allege a violated right with no remedy, which would qualify as a direct constitutional claim — but the standard in his mind was that the infringement was intentional, and all other remedies (aside from federal suit seeking money for damages) had already been pursued. Later, Justice Sotomayor asked,

"What do I do with Blackbeard's Law? It is deeply troubling." Park agreed that it was an unusual law but argued that it didn't have bearing on the case because the law came into being years after the alleged infringements — and Allen had not yet pursued all possible avenues of alternative remedies.

What would Congress need to do to create a more satisfactory answer to the problem than the CRCA? Park answered that Congress would need to show more cases proving a problem, and create fines that were better tailored to infringement (he pointed to a past case where a single mother went bankrupt after facing a $220,000 fine for downloading and sharing images online). Justice Ginsburg later interjected,

"Let me ask one aspect of this question, Mr. Park. States can hold copyrights. They can be copyright holders. And they can sue anybody in the world for infringement. There's something unseemly about a state saying, 'Yes, we can hold copyrights, and we can hold infringers to account to us, but we can infringe to our heart's content and be immune from any compensatory damages.' Could Congress say, 'States, yes you may hold copyrights, but it's conditional that you're liable when you infringe other people's copyright?" Park said he thought not. After a last peppering of questions, the state's argument closed with a warning of potential diminishment of state services for fear of high fines and requesting that the court not assume the state would infringe at any given opportunity.

After a four minute rebuttal, they were done. Reflecting back on the case, Allen said,

"This is the first time ever in the history of United States jurisprudence that somebody had done this. So we really opened a can of worms. But what Allen v. Cooper did was shine a spotlight on a real problem that needs to be addressed. And if I succeed here, I succeed for a lot of people. Not just Disney or Universal … but other people like me, who work in their rooms over the garage. For other filmmakers, for musicians, for software developers." But, for the time being, there was nothing to do but wait.

November 1719

The general court fined Edward Moseley £100 for "scandalous words" and banned him from holding public office for three years.

Given the chance to change their plea on breaking into John Lovick's home, all four men switched their plea to guilty and threw themselves on the mercy of the court. After deliberating for a day, the court returned with fines — £5 for Moore, 20 shillings for Luten, and five shillings for Moseley and Clayton. Moseley recovered from his disputes and ban from public life; by the time he died, Moseley owned more than 30,000 acres of Carolina land and (for better or worse) was seen as one of the colony's prominent citizens. And the damage to Governor Eden's reputation was already seeping into the inlets and creeks of eastern North Carolina. Although Eden and his government had perhaps acted within their rights, they had also stretched the bounds of ethical, above-reproach behavior, extending their own credit a bit too far.

March 23, 2020

The decision arrived; in the midst of other rulings related to a plea of insanity, immigration law, and racial discrimination, the Supreme Court unanimously decided to uphold precedent. Allen's lawyer, Derek Shaffer, called him at home.

"He was crushed," Allen recalled. "He says, 'Rick, I've got bad news.'" The opinion, authored by Justice Elena Kagan, said among other things that Florida Prepaid, where the court held that the Patent Remedy Act — the Copyright Remedy Clarification Act's legislative cousin — overstepped, "all but prewrote our decision today." Elsewhere in the opinion, Justice Kagan noted that the court's conclusion "need not prevent Congress from passing a valid copyright abrogation law in the future." Allen was disappointed, to say the least.

"In copyright, when you create something (whether it's a picture, or a book, or a story, or a piece of music or whatever), you own that. That is your intellectual property, and it's very real property in that regard. And as the owner of that property, just like your home, you have the right to decide what you will and won't do with that property. What the Supreme Court's decision said was that states essentially had a right to interfere in what you do with your own property, without any consequence. That's a problem for all of us."

And so they continue on; copyright issues can be addressed in the legislative branch and the judicial system, and Allen is working on both fronts. Although he said an amended Copyright Remedy Clarification Act would take another six or seven years to be passed and fully tested and affirmed (or not) through the court system, in December he participated in a roundtable for the U.S. Copyright Office's study on sovereign immunity. In the meantime, Allen also says he has a violated right without a remedy, and has filed a motion for reconsideration in the hopes of bringing a direct constitutional claim back to Judge Boyle's court. Intersal is still tied up with the DCR in the state court system. The process has been drawn out, tangled with procedural delays — Reeder said he has sold property, and John Masters (Intersal founder Phil Master's son) has sold a house to keep the suit going.

"About the only thing I can say about this whole situation is that I wish the effort that the state and the Department has put into fighting us had been put into cooperation. It's sad to even think about the stuff that we would've accomplished at this point, if they'd been working with us. But...it is what it is."

The cases and motives are a goulash of case law, principle, a point to prove, and - of course - money. After giving up rights to artifacts, media rights and reproductions are some of the few options Intersal has to recoup its expenses. Their expert witness estimated damages of $129 million in copyright infringements. In a November 2019 press release, Intersal stated that they planned to seek a total of $140 million from the state. Similarly, Nautilus has already lost the chance to document a shipwreck recovery start-to-finish, and stands to lose royalty money. The state also has a dollar amount attached to Blackbeard's name, from tourism to fundraising to saving costs on producing future media.

In the midst of motions, briefs, hearings, appeals, and tangled motives, remnants of the Queen Anne's Revenge are still exposed to the elements on the ocean floor. An estimated 40% of artifacts remain on Beaufort Inlet, untouched since 2015. During interviews for a past publication, state employees expressed concern about the stagnant state of the project, particularly given the site's vulnerability to hurricanes. Although it is a side effect of the suits, neither Allen nor Intersal are happy. All of the parties are at an impasse made of good intentions worn thin and slumping civic-mindedness.

"It's a loss," Allen said. "It's a loss for everyone. Everybody loses here, there's no winners."

In response to a list of questions, a spokeswoman for the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources wrote, "Blackbeard's Queen Anne's Revenge is a significant aspect of North Carolina history, and the QAR project is an important part of the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources' mission of preserving the state's history and educating the state's residents. Unfortunately, I am unable to directly respond to your questions due to the ongoing litigation involving the QAR."

Some housekeeping, before we part ways: The Long Way Around crew is taking February off. We'll see you on the last Friday in March! In the meantime, we'd love to hear from you. Get in touch with feedback, flattery, questions, or outrage here.

Listen to the Supreme Court arguments for yourself.

Read up on architecture at the highest court in the land (More exciting than it sounds - for instance, did you know it actually came in under budget when it was built in the 1930s? That has to be both a first and a last.).

If you're still confused about the court system -- understandable -- may we humbly recommend Crash Course? It has saved many a student's bacon.

IF YOU’D LIKE TO SUPPORT LONG WAY AROUND, PLEASE CONSIDER

FORWARDING TO A FRIEND WHO WILL ENJOY THE SERIES.

NOTES

A note on the notes: This is a weird installment because it's part history, and part more traditional reported story, these notes cover the history part.

five men broke into: NC General Court. Minutes of the General Court of North Carolina, 7/28/1719-8/1/1719. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 159-160. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0185 . Retrieved 7/20/20.

Weeks earlier, they had guided: Captain Ellis Brand to Admiralty Secretary Josiah Burchett, February 6th 1718/19. I can't for the life of me figure out the proper citation for this, I think it's in the Blackbeard file at the state archives.

"much abused by Thach": Ibid.

remnants of his crew and evidence for trial: Ibid.

Pollock wrote that: Pollock, Thomas. Letter to Charles Eden, 12/8/1718. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 159-160. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0172 . Retrieved 7/20/20.

John Lovick's house, nailing the door shut behind them: (NC General Court. Minutes of the General Court of North Carolina, 7/28/1719-8/1/1719. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 159-160. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0185 . Retrieved 7/20/20.

a man who fell squarely on the rebellion side: Pollock, Thomas. Letter to Charles Craven, 2/20/1713. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 20. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0011 Retrieved 9/23/20.

Lovick also later married Eden's step-daughter, Penelope Galland: Bailey et al. "Legends of Black Beard and His Ties to Bath Town: A Study of Historical Events Using Genealogical Methodology." North Carolina Genealogical Society Journal, vol. 28 no. 3, 2002. p. 265

and

http://morebeauforthistory.blogspot.com/p/gallants-pointfirst-owned-by-john.html

Vestryman: NC General Assembly. An Act for Establishing the Church & Appointing Select Vestrys. 1715. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 159-160. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007 https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0106 . Retrieved 7/20/20.

Chief Justice: NC Council. Minutes of the North Carolina Governor's Council, 8/1/1717. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 159-160. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0149>. Retrieved 7/20/20.

secretary: NC Council. Minutes of the North Carolina Governor's Council, 4/3/1719. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 159-160. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0176 . Retrieved 7/20/20.

mid-sixties: LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2013, p. 193

home at the mouth of Bath Creek: Bailey et al. "Legends of Black Beard and His Ties to Bath Town: A Study of Historical Events Using Genealogical Methodology." North Carolina Genealogical Society Journal, vol. 28 no. 3, 2002. p. 252

gathered in the home of Frederick Jones: NC Council. Minutes of the North Carolina Governor's Council, 5/27/1719. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 159-160. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0181 . Retrieved 7/20/20.

Richard Stiles, James "Jemmy" Blake, James White, and Thomas Gates testified: Ibid.

Thatch was in the house with Knight until: NC Council. Minutes of the North Carolina Governor's Council, 5/27/1719. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 159-160. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0181 . Retrieved 7/20/20.

placed the date at September 14th, 1718: Ibid.

"Thache replied he came from Hell": Ibid.

presented a broken piece of it on the spot: Ibid.

"My Friend: If this finds you yet in harbor: Ibid.

Knight was potentially harboring stolen goods: Ibid.

"urged the matter home": Ibid.

”owned the whole matter": Ibid.

"not in any wise howsoever guilty of the least of those crimes": Ibid.

Basilica: Williamson, Hugh. The History of North Carolina, Vol. II. Thomas Dobson, Philadelphia, 1812. p. 8

"kept in prison under the terrors of death": NC Council. Minutes of the North Carolina Governor's Council, 5/27/1719. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 159-160. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0181 . Retrieved 7/20/20.

case throughout many states until after the Civil War:

interviewed Bell about the robbery: NC Council. Minutes of the North Carolina Governor's Council, 5/27/1719. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 159-160. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0181 . Retrieved 7/20/20.

Bell initially pointed his finger at Thomas: Ibid.

Chamberlain also testified: Ibid.

owning up to writing the letter to Thatch: Ibid.

"every lock in his house should be opened to him": Ibid.

”advising the governor not to assist me": Captain Brand to Josiah Burchett dated July 4, 1719. Via NC State Archives, T1/223 E.R. 16-30

he never left his own property: NC Council. Minutes of the North Carolina Governor's Council, 5/27/1719. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 159-160. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0181 . Retrieved 7/20/20.

Chamberlain's testimony added: Ibid.

more ordinary charges: NC General Court. Minutes of the General Court of North Carolina, 10/29/1719-11/3/1719. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 159-160. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0186 . Retrieved 7/20/20.

evidence from two different Bells: NC General Court. Ibid.

brothers-in-law: Duffus, Kevin. "The Last Days of Blackbeard the Pirate" 4th ed., Looking Glass Productions, Raleigh, 2014, p. 169

both lawyers: NC General Court. Minutes of the General Court of North Carolina, 7/28/1719-8/1/1719. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 159-160. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0185 . Retrieved 7/20/20.

"With force and armies": Ibid.

naval office, it also contained the colony's seal: Ibid.

All four men pled not guilty: Ibid.

and

NC General Court. Minutes of the General Court of North Carolina, 10/29/1719-11/3/1719. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 159-160. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0186 . Retrieved 7/20/20.

Seditious speech: Ibid.

"[the government] could easily": Ibid.

"false and malicious": NC Council. Minutes of the North Carolina Governor's Council, 5/27/1719. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 159-160. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0181 . Retrieved 7/20/20.

"he hath behaved himself": Ibid.

settling a will dispute: Ibid.

died two weeks after: Butler, Lindley S. "North Carolina 1718: The Year of the Pirates." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 142.

£100 for "scandalous words": NC General Court. Minutes of the General Court of North Carolina, 10/29/1719-11/3/1719. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 159-160. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0186 . Retrieved 7/20/20.

all four men switched their plea to guilty: Ibid.

£5 for Moore, 20 shillings for Luten, and five shillings: Ibid.