ISSUE № 4: PRIZE VIGNETTES

PRIZE VIGNETTES

Illustration by Kelsey Martin of Kettle Pot Paper

A note: For ease of reading, we have updated the punctuation and spelling in quotes, but left the original content intact. When Blackbeard roamed the seas, the world was split on which calendar system to use — we have converted all French Gregorian dates to fit into the British (Julian) calendar, so the timeline is more clear. We're also playing around with all the variations on the name Thatch, just to keep you on your toes and give you the flavor of first-hand accounts.

"What with the pirates robbing us and the inclination of many of our people to join them, and the Spaniards threatening to attempt these islands we are continually obliged to keep on our guard and our trading vessels in our harbor. Above 100 men that accepted His Majesty's Act of Grace in this place are now out pirating again and except effectual measures are taken the whole trade of America must be soon ruined. "

- Woodes Rogers to the Board of Trade and Plantations, October 31, 1718.

"I fear they will soon multiply for too many are willing to join with them when taken, and with submission if some speedy care [is] not used to suppress them, the trade into and out of the West Indies will greatly suffer, besides the miserable consequences of their inhumanities."

- Lieutenant Governor Bennett of the Bahamas to the Council of Trade and Plantations, May 31, 1718.

If you strip back what we know about Blackbeard to the bare bones of his acts of piracy — what he took, where he took it, and how — he is not particularly revolutionary. Lingering in bays and lurking in passages known to be frequented by merchant ships, drawing near under the pretense of being a fellow trader looking to share news or mail, pursuing a relatively less armed mark in a quick and agile sloop, firing a few warning shots, briefly overwhelming the victim's vessel, and sailing away with stolen goods was hardly original. As an old Greek proverb goes, where there is a sea there are pirates — from the time of the Caesars to current day.

Of Blackbeard's two year career (yes, only two documented years, late 1716 through 1718), records of his first year are patchy. He first appears in the deposition of Henry Timberlake, given on December 17, 1716. Timberlake, captain of a brigantine called the Lamb, said that he was robbed in waters near Hispaniola by an Edward Thach, who was apparently working in tandem with pirate captain Benjamin Hornigold. The next definite encounter: Almost an entire year later in October 1717, Pennsylvania council member Jonathan Dickinson writes that the waters around Philadelphia have "been infested with pirates [including Blackbeard] these three weeks past, taking seven vessels inward and outward bound." Teach was sporadic, "never continuing forty-eight hours in one place," navy captain Ellis Brand wrote in a report to superiors back in England. Even physical firsthand (non-General History of Pirates) descriptions of Blackbeard are difficult to come by. "Deponent says the captain was a tall, spare man with a very black beard which he wore very long," is the most we have to go on, supplemented by an abstract of a letter from Lieutenant Maynard after the battle at Ocracoke which notes, "he let his beard grow, and tied it up with black ribbons."

Two engravings of Blackbeard, made for 1736 and 1724 editions of General History of Pirates, respectively. Not drawn from life, it’s unlikely that either of these illustrations realistically depict the man himself.

The long, black beard is just about the most certain thing about this man. To catalogue the entire career of Edward Thatch or attempt to analyze the inner workings of a man we have so few primary sources on would require a thick volume bloated with caveats and best guesses. With the information we have, we can’t hope for an intricate portrait in full noontime light — instead we're going to hone in on a few key moments that can show us glimmers of his character in his choice of prey, how he operated, and the way his world reacted to him.

Capturing La Concorde

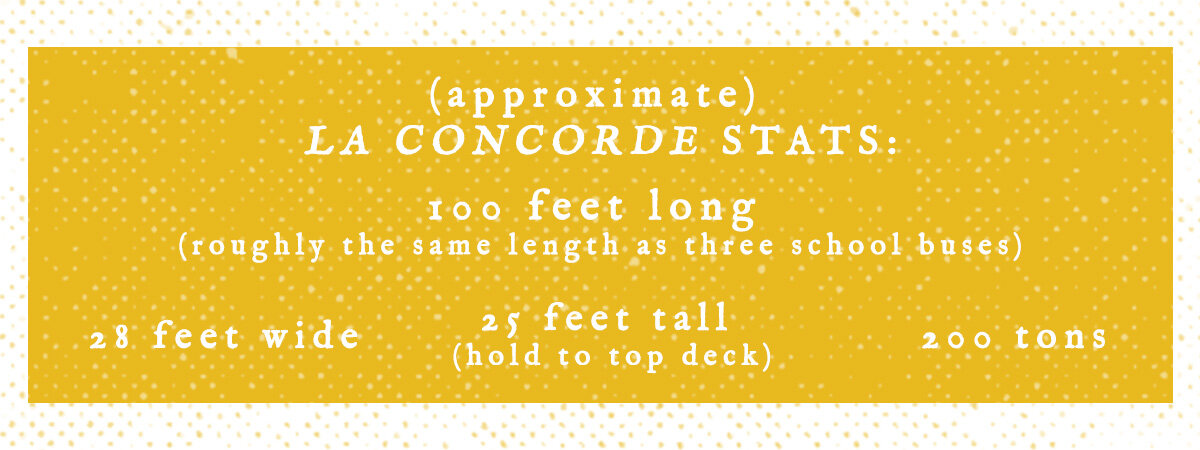

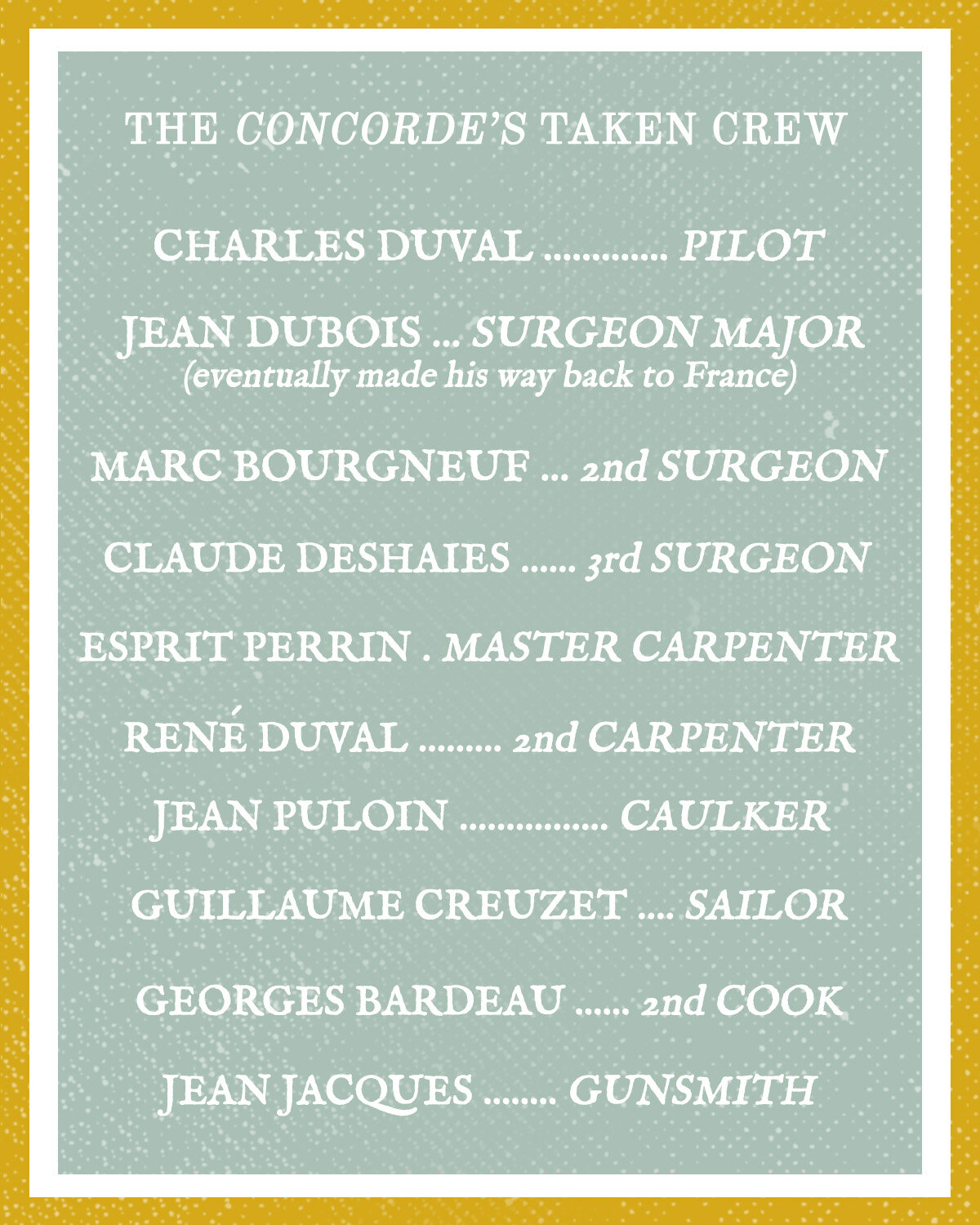

On November 17, 1717, Blackbeard found his flagship. La Concorde's lieutenant later deposed that they encountered the pirates "at about 8 a.m., in a time of mist," in two vessels, one armed with twelve guns (cannon) and the other with eight. Although both of the oncoming sloops were under Blackbeard's command, just a few months earlier one (the Revenge) had been captained by the rather inept Stede Bonnet. After being turned out of command in favor of Blackbeard, according to one newspaper account Bonnet was left more or less to his own devices: "He walks about in his morning gown, and then to his books, of which he has a good library on board." Under Blackbeard's leadership, by this mid-November morning the two pirate vessels were working together in an efficient dance.

The pirates fired off two volleys of cannon and musket fire, which was enough to persuade the crew of La Concorde — already diminished by sickness — to surrender. After the pirates took La Concorde, a cabin boy divulged that the captain and officers had gold dust in their possession. The pirates threatened to cut the necks of La Concorde's men if they did not deliver the gold dust - and stole their clothing in the shakedown. The pirates "searched and visited and robbed them of their cargo and put the rest on said island ashore," leaving the French crew with the conundrum of how to transport 453 people to Martinique with such a small vessel. Most of La Concorde's cargo was not gold dust or fine pewter — it was enslaved people.

Like most trade vessels, La Concorde's owner was not her captain, Pierre Dosset. While her crew was being robbed, her owner, René Mountaudouin, was safe back in La Concorde's home port of Nantes, France. Although slavery was not legal in France proper, it was permitted in French colonies, and the king allowed some breaks in import/export duties for merchants engaged in the slave trade. In 1716, Nantes represented at least 80% of the French slave trade. Ships would wind down the Loire river to open sea carrying goods like brandy, cloth, cowrie shells, and gunpowder to trade for people and gold on the African coasts, then trade the human beings for sugar and other goods in the islands, and complete the triangle by returning to France. Archeological conservator Sarah Watkins-Kenney writes that over seven years, about one third of these voyages out of Nantes were made by Mountaudouin's ships, several by La Concorde herself in 1713, 1715, 1717.

When La Concorde left Nantes for the last time in March 1717, her crew of about 75 had every intent of going about business as usual. As they approached the Judan coast in June, they would likely have put up a partition to separate enslaved men and women and maybe fortified a space in the ship in case of uprising. When they departed Juda in late September, they carried with them 516 souls "of all sexes and ages"; 61 died during the voyage. 16 Frenchmen also died from illness during the crossing. For context, an estimated 10-20% of the enslaved died during their voyage across the Middle Passage, namelessly marked in the logbook with entries like, "bury'd a boy slave No. 25". For English sailors in European waters, the death rate during a voyage was at about 1%. Aboard a ship sailing the slave route, the rate shot up to 20-25% (18% for ships out of Nantes).

Although Blackbeard had no way of knowing it, La Concorde's crew shriveled to 21 able men after 36 more crew members came down sick with either scurvy or dysentery. They were sitting ducks. When Blackbeard left with La Concorde, he took 61 enslaved Africans with him, along with cannon, gear, 10 involuntary crew members, and four volunteers — one of whom was the telltale cabin boy. The pirates left the remaining enslaved people behind with the Concorde's crew on Bequia Island, with barrels of dried beans for basic sustenance (pirates were generally not in the business of murder by starvation). In addition to approximately two tons of beans, the pirates also left behind one of their smaller vessels, which the French wanly renamed Mauvaise Recontre or Bad Encounter.

A slave ship was made to morph, from merchant ship to floating prison and back again in a matter of a few months. La Concorde had served as a privateer in 1710, which perhaps made her ideal for this new metamorphosis, becoming the Queen Anne's Revenge. While testifying on Martinique, Captain Dosset and others left the impression that, "these pirates armed the Vermudie and they will not be satisfied with the harm they have already done." Before Blackbeard fitted up La Concorde for her new purpose, the government perceived he and Bonnet as A Problem. With the Queen Anne's Revenge, they graduated to Official Concern.

The Protestant Caesar

Across the spring months of 1718, reports of Blackbeard roaming the West Indies and taking merchant ships began to pile up. The flotilla grew after capturing and deciding to keep the sloop Adventure (captained by David Herriot, who would later testify against the pirates in Charleston after he was captured with Bonnet's crew, only to be shot in the aftermath of an escape attempt he hatched with Bonnet). By the time Herriot was involved, the crew told him that Bonnet had been out of command for some time, "being turned out of his command by the said Thatch and his pirate crew." The crews of the Queen Anne's Revenge and the Revenge were so interchangeable, vacillated from one ship to another so often, that Herriot could not tell which ship they properly belonged to. As they worked together to capture prizes, the QAR generally provided the muscle and intimidation, while the Revenge did the nimble work of chasing ships down.

Noticeably absent from the depositions of this time are accounts of a madman attacking with his beard aflame — but burning ships was a different matter. In early April 1718, when the pirates took a ship called Land of Promise, Blackbeard declared in no uncertain terms his mission to burn a ship that had given Bonnet the slip. The Protestant Caesar (what a name!) may have escaped once, but Blackbeard was determined not to give her captain the chance for a triumphant return to New England, where he could enjoy admiration for outsmarting and outrunning pirates.

On the morning of April 8, the Protestant Caesar's crew spotted five vessels bearing down on them, "a large ship and a sloop with black flags and deaths heads in them and three more sloops with bloody [red] flags." In a newspaper account verified by the ship's own Captain Wyer and other eyewitnesses, the captain asked his men if they would fight, and "they answered that if they were Spaniards they would stand by him as long as they had life." But after finding out that the big ship (the Queen Anne's Revenge) had 300 men and 40 cannon under the command of Edward Teach, and that one of the sloops was filled with pirates they'd insulted by escaping only a few weeks earlier, "Captain Wyer's men all declared they would not fight and quit the ship believing they would be murdered by the sloop's company, and so all went on shore," leaving the ship to be robbed while they watched from dry ground. According to David Herriot's testimony later that year, Blackbeard sent ahead his quartermaster (William Howard) with eight other men to secure the Protestant Caesar, while in the Revenge a man surnamed Richards corralled four other merchant ships traveling nearby.

Three days after Blackbeard took the Protestant Caesar he extended a curious invitation: Captain Teach sent word that Captain Wyer would not be harmed if he came aboard. On the Queen Anne's Revenge, Thatch told Wyer that he and his crew did well to abandon ship and informed him of his plans to burn the Protestant Caesar, "adding he would burn all vessels belonging to New England for executing the six pirates at Boston." This was a practice of Blackbeard and his crew, telling their captives of their future plans. Some of it was bluster, but there was usually a kernel of truth to it. Over his documented career we know he burnt at least three vessels, including a sloop captured around the same time as the Protestant Caesar. The rationale? Because she belonged to a Captain James of Jamaica, who apparently advertised too freely that he refused to hire sailors who had accepted the Act of Grace (ex-pirates). This was a grudge with a price tag — even discounting a vessel's contents (the best of which would have presumably been cleared pre-kindling), a ship itself could be valuable. When French authorities auctioned off the smaller sloop Blackbeard left La Concorde's crew with, it brought in 3,950 livres.

To large companies like the East India Company, the loss of an entire ship or most of its cargo — though not insignificant — was absorbable. To the small-time traders and officers, the effects could be devastating. After Bonnet stole a ship and all of its contents from Captain Manwaring, the captain later addressed him in court: "You know you did: Which [what Bonnet stole] was my all that I had in the world, so that I do not know but my wife and children are now perishing for want of bread in New England. Had it been only myself, I had not mattered it so much; but my poor family grieves me."

Blackbeard’s plunder was not all — or even mostly — silver and gold.

The burnings represented loss, chaos, and vengeance that far transcended pettiness. When Blackbeard threatened to burn every ship sailing out of New England, to chase down a specific ship, or to even take one of the British navy's ships, they added bonafides to the bluster. Dark, seemingly far-flung prophecies would have carried a more serious weight to the government officials conducting depositions, hearing the threats secondhand from freshly-robbed victims.

Henry Bostock testified that he had told the pirates of the Act of Grace while his ship was being emptied of livestock, gunpowder, books, and linen, “but they seemed to slight it.” Letters from governors throughout the colonies were laced with concern about piracy in general and sprinkled with Thatch in particular, with his looming ship equipped with so many guns and men. News ranged from stolid naval reports to hysteria, rumors blurring the current situation (which, frankly, wasn't great) with the worst case scenario. Blackbeard had already joined up with Bonnet, who for all they knew was a somewhat competent, deep-pocketed threat. And what if they joined forces with Charles Vane or other pirates? The pirates were making a new Madagascar-like hub out of the island of Providence, 800 — no 6,000 — pirates strong. Even with the more modest numbers, the Bahamas's lieutenant governor wrote that, "they will be much superior to what force we can make to oppose them."

Edward Thatch may have been imposing, but he himself did not pose a one-man threat to the wellbeing of the colonies. Blackbeard on the other hand, with a burgeoning reputation he stoked himself, added to the growing anxiety about the true boogeyman: complete interruption of trade. Colonial governors sent letter after letter pleading for backup. From Barbados, governor Robert Lowther wrote that it was not uncommon for sickness, desertion, and death to keep the navy's ships in harbor for two thirds of the year; a letter from South Carolina noted tartly that the Act of Grace "has rather proved an encouragement than anything else, there now being three [pirates] for one there was before the Proclamation was put out."

After the pirates burnt the Protestant Caesar, they let Captain Wyer and his men go, along with the three still-intact sloops that had been traveling with the Protestant Caesar.

Charleston Blockade

Surveyor and naturalist John Lawson wrote in 1709 that Charleston ("Charles Town" back then) had a, "very commodious harbour, about five miles distant from the inlet, and stands on a point very convenient for trade, being seated between two pleasant and navigable rivers. The town has very regular and fair streets, in which are good buildings of brick and wood," plus fortifications. In 1717, Charleston had a population of about 3,000; it was the biggest English town south of Philadelphia, a "potpourri of nationalities and racial groups and a corresponding Babel of languages and sounds," as one historian wrote.

Charleston Harbor's usual bustle was rudely interrupted when, around early June 1718, Blackbeard's flotilla sailed into its bottleneck, blocking access to the ocean. First, they snared the pilot boat (used to ferry pilots out to vessels, to guide them safely into the harbor). Then the pirates captured at least eight more vessels, some carrying "several of our best inhabitants of this place," South Carolina governor Robert Johnson wrote later to the Board of Trade and Plantations. One of the captives was council member Samuel Wragg, along with his four-year-old son, William. Both outgoing and incoming trade came to a crashing halt. With an entire town held hostage, Blackbeard sent his ransom demands ashore with a couple of his men led by Richards, accompanied by one of their captives to press the urgency of the situation home. The pirates demanded the government of South Carolina, "send them a chest of medicines," or else they would, "immediately put to death all the persons that were in their possession, and burn their ships … and threatened to come over the bar for to burn the ships that lay before the town and to beat it about our ears."

A medicine chest seems like a strange ransom, but the pirates had already done fairly well by looting captured ships and stealing personal possessions of their captives. According to Ignatius Pell's testimony, Thatch's men claimed he had taken £1,000 - £1,500 worth of gold and silver from the ships who'd tried to pass. Thanks to lost legislative journals and papers, we know little about the inner workings of this deal — only that the governor must have found the threats to be credible enough to acquiesce, and that Blackbeard, "after plundering [his captives] of all they had, [they] were sent ashore almost naked."

Although the pirates pulled off the blockade with little immediate risk to themselves, to cut off an influential trading town for the better part of a week was effectively thumbing their nose at the Act of Grace. To receive a pardon, reforming pirates had to cease criminal activity by January 5, 1718. Whether out of brazenness or desperation with a dash of wicked glee, in June of 1718, Blackbeard and crew committed some of the most public acts of piracy of the decade, setting colonial governments on edge. Governor Johnson described their year plagued by pirates as "the unspeakable calamity this poor province suffers … we are continually alarmed and our ships taken to the utter ruin of our trade."

Wrecking

According to the Boston News-Letter (a weekly paper, half-sheet printed in two blocky columns on both sides), in Charleston, members of Blackbeard's party stated their intention to head northward, to exact more revenge from New England's vessels. And the pirates did make their way north — about 300 miles north where, after every other member of the flotilla made it through, the Queen Anne's Revenge ran aground in Topsail Inlet. Blackbeard called the Adventure back to help, and it grounded as well, "about [a] gunshot away from the said Thatch," Herriot deposed, using an interesting unit of measure. After assuring Herriot that he would receive at least some of his due for his lost ship, and presumably allowing Bonnet a small boat to go seek a pardon, Edward Thatch went aboard the Revenge and set a betrayal in motion. Ignatius Pell later testified in a Charleston court that Blackbeard "demanded all our arms [weapons], and took our best hands [sailors], and all our provision, and all that we had, and left us." After gutting the Revenge, Blackbeard deposited Herriot, Pell, and about 15 others onto a sliver of sandy island nearby (Herriot: "a league distant from the main[land]; on which place there was no inhabitant, nor provisions"), and sailed away with the flotilla's small remaining sloop packed with 40 white men, 60 Black men, and eight cannon.

The marooning only lasted about a day. When Stede Bonnet (newly pardoned and once again master of the Revenge) rescued the crew, he told them of plans to sail to Saint Thomas to receive a commission and become an upright privateer. Having little choice, the crew went with him, and together they quickly robbed several ships for provisions, and then several more for reasons unconfirmed. Herriot went on to testify that he suspected Blackbeard of running aground on purpose, to downsize the crew and keep the best loot for himself and his new inner circle.

The Rose Emelye

The Queen Anne's Revenge ran aground around the middle of June, and Blackbeard probably arrived in the Bath area shortly afterward, where he surrendered to Governor Eden and received the king's pardon. One would think he made an attempt to at least appear to live up to the conditions of the pardon for a few weeks — but by August 11 (August 11!), Pennsylvania governor William Keith reported to his council that there were reports that "one Teach, a noted pirate, who has done the greatest mischief of any to this place, has been lurking for some days in and about this town."

On August 24 Edward Thatch was in his downsized sloop with a downsized crew, capturing two French ships bound homeward from Martinique, the Rose Emelye (also from Nantes) and Toison d'Or. The reborn pirates took the Rose Emelye, emptying her crew onto the Toison d'Or for a cramped ride back to land, admonishing them to sail fast, or they'd chase them down and burn their vessel too. Then Blackbeard sailed both his old and new ships hundreds of miles back to Ocracoke Inlet. If the crew had admitted foul play, the goods would likely have been condemned as piratically taken and sold at auction with no benefit to the pirates. So they swore they found the ship drifting along with no men aboard, and no identifying papers. Just cask upon cask of valuable dry goods. Governor Spotswood reported three months later that Captain Thatch and crew set fire to the Rose Emelye, destroying any evidence on the pretense (according to General History) that she was a leaky, faulty ship. After Spotwood, "received complaints from diverse of the trading people of that province of the insolence of that gang of pirates, and the weakness of that government to restrain them, I judged it high time to destroy that crew of villains."

Until about ten years ago, historians referred to this ship as "The French Ship" or "The Sugar Ship." She was nameless and almost mythic, the stories of her contents were elastic, stretching to fit the teller. After looking through three years' worth of handwritten depositions, scanning for keywords in French, historian and former curator of nautical archeology at the North Carolina Maritime Museum David Moore found a name: Rose Emelye. According to depositions from her crew and that of the Toison d'Or, along with the ship itself the pirates stole 200 barrels of sugar, thousands of pounds of cocoa, and cotton. This sheds new light on just how credulous — or cynical — officials back in Bath Town must have been, and the information is hard-won.

An aside: Although Moore found the Rose Emelye through documents online, his former colleague from the QAR project, Mike Daniel, found the same depositions around the same time in an archive in Nantes.

"You've got to look under every rock," Moore explained, "Because there's a possibility of some little tidbit being in a letter that ordinarily you would not think would have anything to do with pirate activity, and then be a little something that the author of the letter wrote down at the bottom that dealt with the problems of pirates." His current project: Transcribing the shipping records of South Carolina, Boston, New York, Bermuda, Virginia, Jamaica, Barbados, and Antigua, in hopes of finding one new sliver that could fill in our ever-shifting portrait of Blackbeard.

Conclusion

For nearly 300 years, the popular stories of Blackbeard have dealt in gore, devil's deals, billowing smoke and broken mirrors. The violence in his character stretches large like a shadow puppet, but when brought towards the light it shrinks back into proper proportion. After years of scholarly work piling up, Moore writes that up until his last battle near Ocracoke, we have no documented evidence of Blackbeard killing anyone (plenty of threats, and one on-shore fight resulted in the death of some of his own crew members, but no actual deaths at his hands). While his techniques weren't new, Blackbeard had undeniable street (sea?) smarts. Whether for the thrill of it, or because he was overconfident, or because he had an intimate working knowledge of the power of intimidation, he consistently took on large targets that should have been able to fend him off. While he doesn't appear to have been either entirely a mindless, lucky brute or pure evil genius, quickness and adaptability served him well.

Often the next piece of the puzzle is on paper, in a throwaway footnote of someone's thesis (Moore estimates he has five or six thousand of them saved, just in case), or in a letter in a forgotten box in someone's attic. The trouble with paper is its mutability — it can be yellowed or burnt, scribbled over, crumpled, or dissolved, leaving historians behind to lament their blank spaces. Fortunately, when the paper trail sputters out, there is still another avenue. We can ask questions of the Queen Anne's Revenge herself, as she is pulled from Beaufort Inlet, piece by piece.

If you’d like to learn more on your own, check these out:

Read a copy of The Boston News-Letter

Enjoy this snippet on the QAR’s signal gun.

Skim Spotswood’s letter referencing the Rose Emelye.

Have feedback, questions, or flattery?

Feel free to reach out here.

IF YOU’D LIKE TO SUPPORT LONG WAY AROUND, PLEASE CONSIDER

FORWARDING TO A FRIEND WHO WILL ENJOY THE SERIES.

NOTES

A note on the notes: I’ve dropped all aspirations for MLA formatting for online links. They’re the worst, and I’m busy. Everything else should be decent.

"What with the pirates robbing us and the inclination: Woodes Rogers to Council of Trade and Plantations, October 31, 1718. "America and West Indies: October 1718." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. Ed. Cecil Headlam. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1930. 359-381. British History Online. Web. 26 November 2020. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp359-381.

"I fear they will soon multiply for to many are willing to joyn: Lt. Governor Bennett to the Council of Trade and Plantations. May 31 1718. 'America and West Indies: May 1718', in Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718, ed. Cecil Headlam (London, 1930), pp. 242-264. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp242-264 [accessed 5 November 2020]. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp242-264

Timberlake: Henry Timberlake Deposition, December 17, 1716. Retrieved 2/6/20.

said he was robbed: Henry Timberlake Deposition, December 17, 1716. Retrieved 2/6/20.

"been infested with pirates": Jonathan Dickinson to Lewis Galdy, October 23, 1717, quoted in Moore, David D. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 161

"never continuing forty-eight hours in one place," Ellis Brand to Admiralty Secretary Josiah Burchett, December 4, 1717. Retrieved 2/23/20.

"Deponent says the captain was a tall spare man": Henry Bostock deposition, December 19, 1717. Retrieved 2/23/20.

"he let his beard grow, and tied it up with black ribbons.": Cooke, Arthur L. “British Newspaper Accounts of Blackbeard's Death.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 61, no. 3, 1953, pp. 304–307. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4245947. Accessed 26 Nov. 2020. p. 306

"at about 8 am,": Deposition of Francois Ernaud, April 27, 1718. Retrieved 2/23/20

"He walks about in his morning gown": Boston News-Letter #707, Oct. 28-Nov. 6 1717. Quoted in Moore, David D. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p.162

two volleys of cannon and musket fire: Deposition of Francois Ernaud, April 27, 1718. Retrieved 2/23/20

cabin boy told the pirates: Deposition of Francois Ernaud, April 27, 1718. Retrieved 2/23/20

threatened to cut the necks of La Concorde's men: Deposition of Francois Ernaud, April 27, 1718. Retrieved 2/23/20

stole their clothing in the shakedown: Deposition of Francois Ernaud, April 27, 1718. Retrieved 2/23/20

cannon, gear, 10 involuntary crew members, and four volunteers: Deposition of Francois Ernaud, April 27, 1718. Retrieved 2/23/20

"searched and visited and robbed them": Deposition of Francois Ernaud, April 27, 1718. Retrieved 2/23/20

her owner, René Mountaudouin: Watkins-Kenney, Sarah. "A Tale of One Ship with Two Names: Discovering the Many Hidden Histories of La Concorde and Queen Anne's Revenge." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 187

home port of Nantes, France: Deposition of Francois Ernaud, April 27, 1718. Retrieved 2/23/20 and

Pierre Dosset deposition, April 27, 1718. Retrieved 2/23/20.

the king allowed some breaks in import/export duties for merchants engaged in the slave trade: Watkins-Kenney, Sarah. "A Tale of One Ship with Two Names: Discovering the Many Hidden Histories of La Concorde and Queen Anne's Revenge." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 192

In 1716, Nantes represented at least 80%: Watkins-Kenney, Sarah. "A Tale of One Ship with Two Names: Discovering the Many Hidden Histories of La Concorde and Queen Anne's Revenge." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 192

with goods like brandy, cloth, and gunpowder: Watkins-Kenney, Sarah. "A Tale of One Ship with Two Names: Discovering the Many Hidden Histories of La Concorde and Queen Anne's Revenge." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 195

one third of these voyages out of Nantes: Watkins-Kenney, Sarah. "A Tale of One Ship with Two Names: Discovering the Many Hidden Histories of La Concorde and Queen Anne's Revenge." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 192

March 1717: Minutes from Martinique, December 10, 1717. Retrieved 2/23/20.

and

Watkins-Kenney, Sarah. "A Tale of One Ship with Two Names: Discovering the Many Hidden Histories of La Concorde and Queen Anne's Revenge." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p.198

about 75: Deposition of Francois Ernaud, April 27, 1718. Retrieved 2/23/20

and

Pierre Dosset deposition, April 27, 1718. Retrieved 2/23/20.

put up a partition to separate enslaved men and women: Watkins-Kenney, Sarah. "A Tale of One Ship with Two Names: Discovering the Many Hidden Histories of La Concorde and Queen Anne's Revenge." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 207

fortified a space in the ship in case of uprising: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998 p. 77

"of all sexes and ages": Deposition of Francois Ernaud, April 27, 1718. Retrieved 2/23/20

61 died during the voyage: Pierre Dosset deposition, April 27, 1718. Retrieved 2/23/20.

16 Frenchmen also died from illness: Watkins-Kenney, Sarah. "A Tale of One Ship with Two Names: Discovering the Many Hidden Histories of La Concorde and Queen Anne's Revenge." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 199

10-20% of the enslaved died: na. “Africans in America, Part 1: The Middle Passage.” PBS, www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part1/1p277.html. Accessed 15 Nov. 2020.

Further reading: Cohn, Raymond L. “Deaths of Slaves in the Middle Passage.” The Journal of Economic History, vol. 45, no. 3, 1985, pp. 685–692. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2121762. Accessed 13 Nov. 2020.

"bury'd a boy slave No. 25": Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998 p. 78

death rate during a voyage was at about 1%: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998 p. 130

rate shot up to 20-25%: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998 p. 130

18% for ships out of Nantes: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998 p. 226

21 able men: Deposition of Francois Ernaud, April 27, 1718. Retrieved 2/23/20

36 more crew members came down sick with either scurvy or dysentery: Deposition of Francois Ernaud, April 27, 1718. Retrieved 2/23/20

he took 61 enslaved Africans with him: Dolin, Eric Jay. Black Flags, Blue Waters. New York City, Liveright Publishing Corp, 2018. p. 214

remaining enslaved people behind with the Concorde's crew on Bequia Island, with barrels of dried beans: Minutes from Martinique, December 10, 1717. Retrieved 2/23/20.

approximately two tons of beans: Moore, David D. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 165

renamed Mauvaise Recontre: Watkins-Kenney, Sarah. "A Tale of One Ship with Two Names: Discovering the Many Hidden Histories of La Concorde and Queen Anne's Revenge." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 200

served as a privateer in 1710: Watkins-Kenney, Sarah. "A Tale of One Ship with Two Names: Discovering the Many Hidden Histories of La Concorde and Queen Anne's Revenge." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p.187

"these pirates armed the Vermudie": Minutes from Martinique, December 10, 1717. Retrieved 2/23/20.

capturing and deciding to keep the Adventure: David Herriot deposition, October 24, 1718. Printed in Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p. 179

"being turned out of his command by the said Thatch and his pirate crew" : David Herriot deposition, October 24, 1718. Printed in Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p. 180.

interchangeable, vacillated from one ship to another: David Herriot deposition, October 24, 1718. Printed in Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p. 180

Land of Promise, and Blackbeard declared: Boston News-Letter #739, June 9-16, 1718. Quoted in Moore, David D. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 170

morning of April 8 the Protestant Caesar's crew spotted five vessels: Boston News-Letter #739, June 9-16, 1718. Quoted in Moore, David D. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 171

"a large ship and a sloop with black flags": Boston News-Letter #739, June 9-16, 1718. Quoted in Moore, David D. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 171

"they answered that if they were Spaniards they would stand by him as long as they had life": Boston News-Letter #739, June 9-16 1718. Quoted in Moore, David D. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p.171

"Captain Wyer's men all declared they would not fight": Boston News-Letter #739, June 9-16, 1718. Quoted in Moore, David D. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 171

Richards in the Revenge corralled four other merchant ships traveling nearby: David Herriot deposition, October 24, 1718. Printed in Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p. 180

Three days after Blackbeard took the Protestant Caesar: Boston News-Letter #739, June 9-16, 1718. Quoted in Moore, David D. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 171

"adding he would burn all vessels belonging to New England": Boston News-Letter #739, June 9-16, 1718. Quoted in Moore, David D. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 171

Because she belonged to a Captain James of Jamaica: David Herriot deposition, October 24, 1718. Printed in Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p. 181

3, 950 livres: Deposition of Francois Ernaud, April 27, 1718. Retrieved 2/23/20

"You know you did": "The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet, and Other Pirates" Benjamin Cowse, London, 1719, p. 39. Via the Library of Congress, American Memory Collection, N.D. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/service/lawlib/law0001/2010/201000158861859/201000158861859.pdf

threatened to burn every ship sailing out of New England: William Wade deposition, May 15, 1718. Retrieved 2/23/20.

take one of the British navy's ships: Martin Preston Deposition, May 16, 1718. Retrieved 2/23/20.

“but they seemed to slight it": Henry Bostock deposition, December 19, 1717. Retrieved 2/23/20.

Charles Vane: Woodes Rogers to Council of Trade and Plantations, October 31, 1718. "America and West Indies: October 1718." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. Ed. Cecil Headlam. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1930. 359-381. British History Online. Web. 26 November 2020. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp359-381.

800: James Logan to Robert Hunter, October 24, 1717. Quoted in Moore, David D. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p.161.

6,000 pirates strong: Deposition of Christopher Taylor, January 12, 1718. Retrieved 2/20.

"they will be much superior to what force we make to oppose them":, Lt. Governor Bennett to the Council of Trade and Plantations. May 31 1718. 'America and West Indies: May 1718', in Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718, ed. Cecil Headlam (London, 1930), pp. 242-264. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp242-264 [accessed 5 November 2020]. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp242-264

sickness, desertion, and death kept the navy's ships in harbor: Lowther to Board of Trade and Plantations, July 20, 1717. "America and West Indies: July 1717, 17-31." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 29, 1716-1717. Ed. Cecil Headlam. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1930. 344-364. British History Online. Web. 24 November 2020. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol29/pp344-364.

"has rather proved an encouragement": Extracts of several letters from South Carolina, June, 13 1718. "America and West Indies: August 1718." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. Ed. Cecil Headlam. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1930. 327-343. British History Online. Web. 26 November 2020. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp327-343.

along with three out of the four other sloops that were traveling with the Protestant Caesar: David Herriot deposition, October 24, 1718. Printed in Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p.181

"very commodious harbour": Lawson, John. “A New Voyage to Carolina.” John Lawson, 1674-1711. A New Voyage to Carolina. Academic Affairs Library, UNC-Chapel Hill , 2001, docsouth.unc.edu/nc/lawson/lawson.html. p. 2

population of about 3,000: Dolin, Eric Jay. Black Flags, Blue Waters. New York City, Liveright Publishing Corp, 2018. p. 206

biggest English town south of Philadelphia: LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2013. p. 96-7

"potpourri of nationalities": Charleston! Charleston! by Walter J. Fraser Jr. quoted in Dolin, Eric Jay. Black Flags, Blue Waters. New York City, Liveright Publishing Corp, 2018. p. 207

around early June 1718, Blackbeard's flotilla sailed: Governor Johnson to the Council of Trade and Plantations, June 18, 1718. "America and West Indies: June 1718." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. Ed. Cecil Headlam. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1930. 264-287. British History Online. Web. 9 November 2020. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp264-287.

First, they snared the pilot boat: Governor Johnson to the Council of Trade and Plantations, June 18, 1718. "America and West Indies: June 1718." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. Ed. Cecil Headlam. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1930. 264-287. British History Online. Web. 9 November 2020. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp264-287.

at least eight more vessels: Governor Johnson to the Council of Trade and Plantations, June 18, 1718. "America and West Indies: June 1718." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. Ed. Cecil Headlam. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1930. 264-287. British History Online. Web. 9 November 2020. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp264-287.

"several of our best inhabitants": Governor Johnson to the Council of Trade and Plantations, June 18, 1718. "America and West Indies: June 1718." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. Ed. Cecil Headlam. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1930. 264-287. British History Online. Web. 9 November 2020. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp264-287.

One of the captives was council member: Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p. 79

four-year-old son, William: Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p. 79

a couple of his men led by Richards: Extracts of several letters from South Carolina, June, 13 1718. "America and West Indies: August 1718." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. Ed. Cecil Headlam. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1930. 327-343. British History Online. Web. 26 November 2020. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp327-343.

accompanied by one of their captives: Extracts of several letters from South Carolina, June, 13 1718. "America and West Indies: August 1718." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. Ed. Cecil Headlam. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1930. 327-343. British History Online. Web. 26 November 2020. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp327-343.

"send them a chest of medicines,": Extracts of several letters from South Carolina, June, 13 1718. "America and West Indies: August 1718." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. Ed. Cecil Headlam. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1930. 327-343. British History Online. Web. 26 November 2020. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp327-343.

"immediately put to death all the persons that were in their possession, and burn their ships" Extracts of several letters from South Carolina, June, 13 1718. "America and West Indies: August 1718." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. Ed. Cecil Headlam. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1930. 327-343. British History Online. Web. 26 November 2020. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp327-343.

L1,000 - L1,500: Ignatius Pell deposition, October 24, 1718. Printed in Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p.189-90

lost legislative journals and papers: Butler, Nic. “The Charleston Pirate Trials of 1718.” Charleston County Public Library, 4 Jan. 2019, www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/charleston-pirate-trials-1718.

"after plundering [his captives] of all they had, [they] were sent ashore almost naked": Governor Johnson to the Council of Trade and Plantations, June 18, 1718. "America and West Indies: June 1718." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. Ed. Cecil Headlam. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1930. 264-287. British History Online. Web. 9 November 2020. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp264-287.

for the better part of a week: David Herriot deposition, October 24, 1718. Printed in Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p. 181

January 5, 1718: Act of Grace, printed in Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p. 177

"The unspeakable calamity": Governor Johnson to the Council of Trade and Plantations, June 18, 1718. "America and West Indies: June 1718." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. Ed. Cecil Headlam. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1930. 264-287. British History Online. Web. 9 November 2020. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp264-287.

intention to head northward: Boston News-Letter, June 30-July 7, 1718. Quoted in Dolin, Eric Jay. Black Flags, Blue Waters. New York City, Liveright Publishing Corp, 2018. p. 220.

after every other member of the flotilla made it through: David Herriot deposition, October 24, 1718. Printed in Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p. 182

"about [a] gunshot from the said Thatch": David Herriot deposition, October 24, 1718. Printed in Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p. 182

assuring Herriot that he would receive at least part of his due: David Herriot deposition, October 24, 1718. Printed in Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p. 182

"Demanded all our arms": "The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet, and Other Pirates" Benjamin Cowse, London, 1719, p. 11. Via the Library of Congress, American Memory Collection, N.D. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/service/lawlib/law0001/2010/201000158861859/201000158861859.pdf

Herriot, Pell, and about 15 others: David Herriot deposition, October 24, 1718. Printed in Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p. 182

"a league distant from the main": David Herriot deposition, October 24, 1718. Printed in Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p. 183

packed with 40 white men, 60 Black men, and eight cannon: David Herriot deposition, October 24, 1718. Printed in Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p. 183

Herriot's marooning only lasted about a day: David Herriot deposition, October 24, 1718. Printed in Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p. 183

newly pardoned: Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p. 87

told them of plans to sail to Saint Thomas to receive a commission: David Herriot deposition, October 24, 1718. Printed in Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p. 183

they quickly robbed several ships for provisions, and then several more for reasons unconfirmed: "The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet, and Other Pirates" Benjamin Cowse, London, 1719, p. 11-12, 14-15. Via the Library of Congress, American Memory Collection, N.D. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/service/lawlib/law0001/2010/201000158861859/201000158861859.pdf

suspected Blackbeard of running aground on purpose: David Herriot deposition, October 24, 1718. Printed in Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p. 184

he surrendered to Governor Eden and received the king's pardon: Captain Vincent Pearce to Josiah Burchett, September 5, 1718. Quoted in Moore, David D. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 175.

"one Teach, a noted pirate, who has done the greatest mischief": Minutes of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania, From the Organization to the Termination of the Proprietary Government, Volume 3. Quoted in Moore, David D. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 178.

August 24: Moore, David D. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 178

bound homeward from Martinique: Spotswood to James Cragg, May 26 1719. Retrieved January 2020.

admonishing them to sail fast, or they'd chase them down and burn their vessel too: Woodard, Colin. “The Last Days of Blackbeard.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 1 Feb. 2014, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/last-days-blackbeard-180949440/. Accessed 11/15/20

hundreds of miles back to Ocracoke Inlet: Moore, David D. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 178

they had found the ship drifting along: Spotswood to James Cragg, October 22, 1718. Retrieved 1/22/20.

swore no men aboard, and no identifying papers: Spotswood to James Cragg, May 26 1719. Retrieved January 2020.

and

Williamson, Hugh. The History of North Carolina, Vol. II. Thomas Dobson, Philadelphia, 1812. p. 6.

Just cask upon cask of valuable dry goods: Spotswood to Board of Trade and Plantations, December 22, 1718. "America and West Indies: December 1718, 22-31." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. Ed. Cecil Headlam. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1930. 424-446. British History Online. Web.11/23/20. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp424-446.

Captain Thatch and crew set fire: Spotswood to Board of Trade and Plantations, December 22, 1718. "America and West Indies: December 1718, 22-31." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. Ed. Cecil Headlam. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1930. 424-446. British History Online. Web.11/23/20. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp424-446.

pretence (according to General History) that she was a leaky: Johnson, Charles. A General History of Pirates. Second Ed., T. Warner, London, 1724, p. 76.

"received complaints from diverse": Spotswood to Board of Trade and Plantations, December 22, 1718. "America and West Indies: December 1718, 22-31." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718. Ed. Cecil Headlam. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1930. 424-446. British History Online. Web.11/23/20. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp424-446.

Mike Daniel, also found documentation around this time in the Nantes archives: Woodard, Colin. “The Last Days of Blackbeard.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 1 Feb. 2014, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/last-days-blackbeard-180949440/. Accessed 11/15/20

the pirates stole 200 barrels of sugar… : Moore, David D. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 178

we have no documented evidence of Blackbeard killing anyone: Moore, David D. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 184

on-shore fight resulted in the death of some of his own crew members: Disorders caused by the Pirates, December 21 1717. Retrieved 2/23/20

Graphics:

How many guns are a lot of guns?

Bellamy: Lt. Governor Bennett to the Council of Trade and Plantations, July 30, 1717. ( 'America and West Indies: July 1717, 17-31', in Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 29, 1716-1717, ed. Cecil Headlam (London, 1930), pp. 344-364. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol29/pp344-364 [accessed 23 October 2020].)

Hornigold and Jennings: Deposition of Matthew Musson, July 5, 1717. Retrieved 2/23/20.

Charles Vane: Lt. Governor Bennett to the Council of Trade and Plantations. May 31 1718. 'America and West Indies: May 1718', in Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 30, 1717-1718, ed. Cecil Headlam (London, 1930), pp. 242-264. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp242-264 [accessed 5 November 2020]. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp242-264

La Concorde Stats: Watkins-Kenney, Sarah. "A Tale of One Ship with Two Names: Discovering the Many Hidden Histories of La Concorde and Queen Anne's Revenge." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 199