ISSUE № 2: TEACH'S WORLD

TEACH’S WORLD

Illustration by Kelsey Martin of Kettle Pot Paper. Let it also be known that the people have spoken, and they have named the sea serpent Sedgwick.

Most quotes have been updated with standard spelling, capitalization, and punctuation.

November 4, 1718

About two weeks before Edward Teach lost his head near Ocracoke, an alarming report from Tobias Knight reached the governor's council, meeting in the home of Thomas Pollock. A "great body of Indians now about Bath Town" had kidnapped the son and daughter of Thomas Worsley, a planter in the area, plus his servant named Nathaniel Ming and a difficult-to-identify enslaved man. Rangers scouring the area reclaimed the son, John Worsley, and sensed some crookedness in his story.

Roughly a week before the pirate's last standoff, a Captain John Worley's testimony condemns the children and their tale. The whole kidnapping story was "a villainous confederacy of Mr. Worsley's children and servants, with his slave Pompey", fabricated to keep Pompey out of trouble for some transgression (Pompey was presumably enslaved by Thomas Worsley; council minutes are not specific). The council orders Thomas Worsley to pay a £500 bond for the chaos the group almost caused, and to bring his daughter Mary to attend the next court or council session for further instruction. John was condemned to receive "39 lashes well laid on his bare back".

39 lashes is heavy punishment to bear for a lie, particularly to the modern eye. But young John Worsley grew up in a much different world. The land of North Carolina was vast, stubborn, and wild. Because of the long miles between good Anglicans, Governor Eden fretted over those "seduced by Quakerism", a shift with meaningful political consequences. In one of many frustrated letters, Reverend John Urmston (one of very few officially-sanctioned ministers in Carolina) wrote that the colony's people were at a near-constant stretch to make ends meet.

To understand what was happening in North Carolina in November 1718, you're going to need to know something about the rest of the world, and the people in it. The goal of this issue is to give you framework, knowledge, and tools that will be useful over the next six installments, to eventually make the seemingly strange and distant past more present and familiar.

Distant Snapshot

In the early 1700s, Bach labored over his first cantatas, young Frederick the Great learned how to walk, Ben Franklin's older brother taught him how to set type in a printing press, and Voltaire was imprisoned in the Bastille because of a bawdy satirical poem he wrote about French royalty. China had transitioned into the Qing dynasty and was about to usher in the best years for that line. During 1707 alone, the United Kingdom was created, 27 consecutive years of war in India between the Maratha and Mughal empires paused, and Mount Fuji erupted, covering Edo (Tokyo) with ash from 60 miles away. In 1712, descendants of the Maya began to rebel against Spanish rule from the highlands of Mexico. In Russia, Peter the Great was firmly establishing his homeland as a formidable European power, and in 1718 had his oldest son Alexei tortured to the point of death for allegedly conspiring to take the throne. European explorers had just brushed the coast of Australia, while the Makasar people of modern-day Indonesia established trade with the Aboriginal people during their annual excursions to harvest sea cucumbers.

In Europe, the main powers reaching out to grasp the New World were France, England, and Spain (plus Portugal and the Netherlands, depending on the region). After a failed settlement attempt on Roanoke, England set down a settlement in Jamestown, which eventually bloomed outwards as far north as Newfoundland and down to South Carolina. The Spanish laid quick and seemingly irreversible claim to much of South America; holdings along the African coast and islands in the West Indies (the Caribbean area) were much more scattered. Under Oliver Cromwell, England tried to claim Hispaniola (Haiti) and ended up settling for mostly-deserted Jamaica to ensure that there were protestants in the West Indies.

Land was not just land, after all — it was a chance to determine what the rest of the world would look like for centuries. For operators like Sir Francis Drake (one of the first gentleman privateers), stealing from the Spanish under an English banner was not only lucrative, it was a chance to serve queen and country and Moral Good — and Spanish privateers felt similarly justified. England, France, and Spain spent the late 17th century in wavering alliances, France and England ganging up on Spain only to be back at war with each other within a few years. The War of Spanish Succession (1701-1713) ushered in a flood of privateers (more or less state-sanctioned pirates who stole from opposing nations) for all parties involved; England actively warring with both France and Spain was a concern on both land and sea. Surveyor and amateur naturalist John Lawson wrote worriedly in 1712 to an English audience that France was more strategic about their settling (the subtext: this would not do).

Who rules?

Once third in line for the English throne, and for a time not in line at all, Queen Anne reigned through most of the War of Spanish Succession. Anne was known for her ill health, poor eyesight, and eighteen pregnancies that resulted in no surviving heirs.

Queen Anne, the last Stuart monarch.

In 2020, royal succession feels inevitably stable. How Anne came to the throne is emblematic of the instability of an ongoing identity crisis that overshadowed English government for a hundred years.

In 1625 Anne's great uncle, Charles I, inherited the crown from his father, along with a stubborn belief in divine right, and a tenuous relationship with Parliament. Those tensions came to a (lost) head with the English Civil War; Charles I's death warrant was signed and sealed by Oliver Cromwell (former revolutionary, future Lord Protector). The foray away from monarchy and into a commonwealth ended in 1660 with Cromwell's son Richard, who abdicated and fled to Paris six months after succeeding Oliver. Charles II (who had himself fled to France before his father's beheading) was brought back to rule.

Although Charles II flirted with Catholicism, he ensured his openly Catholic brother James's daughters, Mary and Anne, were raised in the Anglican church. Charles II had 14 illegitimate children, but no legitimate heir. When James II was inevitably deposed, Mary stepped into place with her husband William of Orange. This couple was also childless; when both died, Anne reigned for 12 years, dodging partisanship from both sides and truly pleasing neither Whig nor Tory even up til her death with no heirs in 1714. Out of eligible, protestant Stuarts, the United Kingdom turned to a Hanover cousin from Germany — King George I. George was technically 52nd in line and did not speak fluent English, but at least he was protestant. His detractors called him "The Turnip King", a dig at the supposedly backwards Hanover region.

As monarchs shifted, so did England/Britain's relationship to the colonies, and the shape of the colonies themselves. Under Charles I, land was set aside for a colony named Coralana, after the Latin version of Charles. Under Charles II, the name was softened to Carolina, and the land was bestowed upon eight Englishmen who had been loyal to both Charleses. The arrangement was called "proprietorship", the eight men and their heirs the Lords Proprietors. Their lands were technically still subject to English law, but the Lords Proprietors were responsible for the colony's administration, could tax inhabitants, and could sell off parcels of land as they saw fit.

Desperate Fortunes in the West Indies

After the Spanish started extracting large quantities of gold from the Aztecs and Inca, historian A. P. Thornton writes that the Caribbean became, "a cauldron where the blood of Europe boiled at will." Jamaica in general and Port Royale in particular became a home for, "people of desperate fortunes." In 1717, a mob in Kingston actually rescued a convicted pirate from the gallows. But before there were pirates, buccaneers roamed the islands, radiating out from Hispaniola, where they began as scavengers, and carving out an existence from hunting wild boars and occasional sea robbery.

Most buccaneers would have been happy to be small-time operators, living by the new customs of the coast and doing whatever they could get away with. But when the Spanish escalated attempts to clear the area, buccaneers responded in kind. In 1666 Jean-David Nau, alias François L'Olonnais (who had escaped death at the hands of the Spanish by smearing himself with blood and playing dead amongst his own deceased crew members), sacked Gibraltar on the coast of Venezuela, gaining 30,000 pieces of eight just in ransom money for citizens he captured. This handsome prize made it easy to collect up a crew back on Tortuga, where buccaneers would go to replenish their supplies and spend their winnings, "with great liberality, giving themselves freely to all manner of vices and debauchery, among which the first is that of drunkenness, which they exercise for the most part with brandy; this they drink as liberally as the Spaniards do clear fountain-water."

Although the buccaneers’ heyday was 60 years before Blackbeard's time, governors were haunted by the threat of another stronghold, another chance entire cities would be sacked and left to smolder for a month.

Trade

In general, Europe sent out manufactured goods like cloth, porcelain, instruments (both medical and musical), and heavy weaponry, while the colonies exported goods made from natural resources (timber, fur, pitch, produce, etc.). The trade triangle connected at the coasts of Europe, the colonies, and Africa, where ivory, gold, and human beings were purchased for goods. The enslaved bore the burden of creating the cash crop of the era, sugar. They are the human backdrop for much of Europe's economic development in the colonies — planting, cultivating, and harvesting sugar cane, crushing the stalks and then tending vats of molasses as they boiled and boiled and boiled, all while contending with disease, hunger, and heat that made the air itself seem heavy.

Life on the Water

The world as most knew it, with earth underfoot, was complex enough. Add a slew of people in a floating, tight space, and the usual complications of human nature multiply. How you fared depended on the vessel you found yourself in, what route it took, who was in charge, and where you fell in the pecking order.

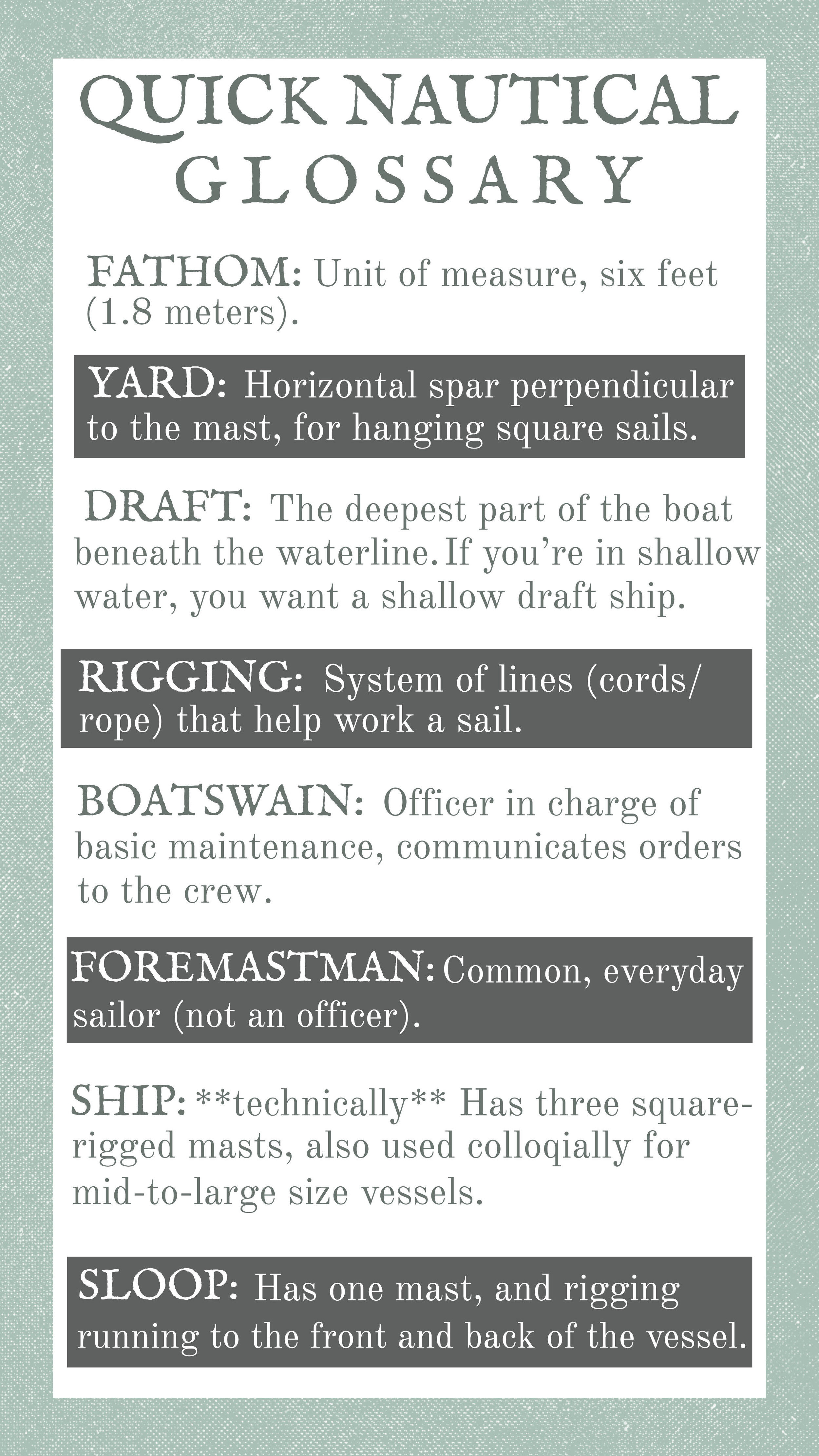

Glossaries adapted and expanded from this wonderful list, see notes for full credits.

A sailor stored all the personal possessions he would need on a voyage in his sea chest. This included clothing (distinctives: shirts with checks or striped patterns and breeches with wide legs, all preferably made from canvas, ticking, or cotton), bedding (hammocks, quilts), tobacco and/or strong drink in some form, incidentals for personal upkeep (sewing kit, razors), books, some cash, and ingredients like sugar, bacon, and spices to make their rations more palatable. Most common sailor's quarters were in the forecastle (pronounced "focsle"), a section of the ship accessed by a hatch, where the floors were filled with chests, and hammocks were slung between beams that made the low ceilings even lower. In bad weather the hatch was shut, and the air would grow close with damp and the smell of unwashed — or at best, less-than-ideally-washed — sailor.

Food

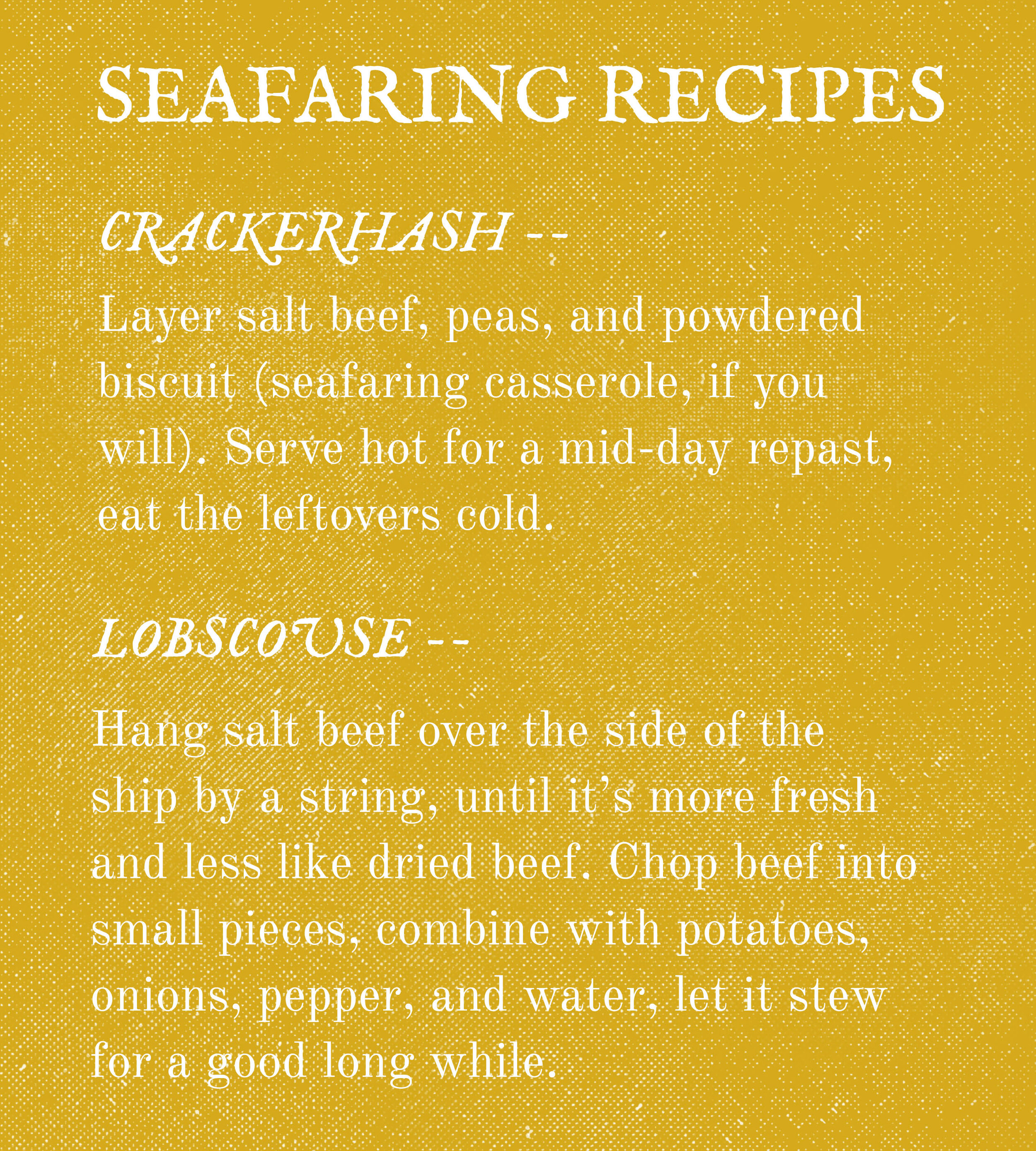

On merchant ships, a standard ration was one pound of meat, one pound of bread (hard biscuits), and some combination of other fixings like dried peas or cheese per man per day, usually eaten in shifts of three to five men. Whenever possible, cooks supplemented their supplies with fresh local food/catches, however exotic. Contemporary accounts include flamingo tongues, albatross, tortoise (one cook wrote that a big one could feed 40-50 men), and shark tail ("parboiled and fried with onions is pretty good eating").

For many seamen, life slipped by in a rhythm of four-hour watches, with an occasional two-hour dogwatch to make sure the work was divided evenly. The work itself varied by position, by weather, by location; when nothing was pressing, there was always maintenance (caulking, scraping, scrubbing, stitching) to do.

Danger at Sea

"Sea-men are … to be numbered with the living nor the dead: their lives hanging continually in suspense before them," minister John Flavel wrote in a 1682 pamphlet. This statement rings true for merchants, pirates, and navy men alike. Besides normal workplace accidents like falling from the yard, there was about a 3-5% chance of wrecking, fear of facing the elements on the open sea (sailors were known to keep a wary eye out for "storm-raisers" — dolphins, cats, and halcyon), not to mention the biggest killer: Disease. There was scurvy, "bloody flux" (dysentery), malaria, and "ship fever" (typhus), which had a reputation for easily ripping through an entire vessel. Treatment could be worse than disease. Bleeding was a catch-all remedy, and one sailor put down in his journal that a ship's surgeon did little for a sailor but, "feeling his pulses when he is half dead, asking when he was at stool, and how he feels himself, and how he slept, and then giving him some of their medicines upon the point of a knife, which doeth as much good to him as a blow upon the pate [head] with a stick."

An aside: In some cases, mutinies started by handing the captain or officer a "round robin", a paper with the crew's written intentions, and their signatures in a circle, so no one could be accused of being the first to sign or claim to be the last to sign under duress if the mutiny was unsuccessful or they encountered the authorities.

Discipline

On trade ships, punishments for misbehavior ranged from the captain deducting three day's wages from a sailor's pay to having a thief run a gauntlet composed of his shipmates, from moderate beating to being locked in irons. Punishment particularly associated with the navy was keel-hauling, dragging a man under and scraping him across the bottom of the ship; almost drowning him, and inflicting immense pain and panic in the process. Navy or no, if a sailor felt he had been mistreated there was little recourse; the court systems were unfriendly to such claims, and mutiny was a last resort. Perhaps this added appeal to the idea of joining a pirate ship, where the punishment process could involve a jury of the wrongdoer's peers and a vote on the proper punishment. Pirate captain Bartholomew "Black Bart" Roberts is credited with this contrast of the two lives: "In an honest service, there is thin commons, low wages, and hard labor; in this [piracy], plenty and satiety, pleasure and ease, liberty and power; and who would not balance creditor on this side, when all hazard that is run for it, at worst, is only a sour look or two at choking. No, a merry life and a short one, shall be my motto."

A Pirate's Life

(in strictly general terms. we'll get to the nuance in later issues, pinky promise. for right now, the big picture)

On a ship with generally law-abiding inhabitants, living/sleeping quarters were determined by hierarchy; pirates worked more on a first-come-first-serve basis, a sign of their more egalitarian philosophy. The captain was still in charge, but he was elected by a simple majority, could be deposed (or "turn'd before the mast") by a vote of the council, and he was only truly unquestionable in the heat of battle. Far more than a carefree thief-in-chief, a captain needed to have a working knowledge of navigation, and the ability to manage people from all over the world — under pressure and when they were bored. The captain would work closely with the boatswain and quartermaster (distributer of prize money and general order keeper), also elected positions. Regular general councils would have included all of the ship's voluntary occupants and settled matters such as deciding their course, electing leadership, and resolving disputes. Pay was in proportion to contribution to the voyage, but the gap was not wide — the average man got one full share, while the captain might get one and a half or two shares; this effectively made their payouts less like wages to an employee and more like dividends to a shareholder.

Most pirates of the Golden Age operated out of shallow draft sloops, sometimes joining forces to make two-or-three ship flotillas. Each ship might have 10 guns and a maximum of about 100 men. The pirates sailing into the big leagues converted large prizes into men-of-war, carrying both more guns and more men.

Standard Piracy

During the Golden Age of Piracy (ca. 1695-1725), freebooters prowled the "pirate round", cruising main trade routes from New England to Gambia — sometimes in open waters, often darting out from behind a strip of land when they spotted approaching prey. While nations had standardized flags, the anti-national pirates were more eclectic, centered around the key elements of a skeletal figure (either in full, or a simple "death's head" skull), a weapon, and blood or a vital organ, all on a field of black. By the Golden Age's zenith, most merchant captains realized fleeing was not likely to be successful or worth the potential trouble it could cause. The robbery itself tended to be fairly systematic: Pirates would corral the caught crew into one area (on shore, on the deck of the merchant ship, or sometimes the pirate ship), inquiring about what goods they were carrying and how they were treated. Were the conditions fair, or was the captain heavy-handed? Usually, the pirates released their victims with little more trouble than a vessel with a lightened load. But just often enough, pirates destroyed a ship with meagre provocation, avenged a captain's mistreatment of his crew, or tortured a crew member to extract information about hidden gold or goods (the most common tactic: tying matches to a sailor's fingers, and letting them burn down. An unusual but memorable technique was "woolding", or tightening a rope around the potential informant's head until the pressure practically popped his eyes out) . So it was systematic, but the system had several sticks of dynamite at its base.

An aside: According to maritime historian (and patron saint of too many footnotes in this installment) Peter Earle, particularly harsh captains were sometimes put through an ordeal called “blooding and sweating”. The captain would be stripped and forced to run a gauntlet of the crew who were each armed “with a sail-needle, pricking him in the buttocks, back, and shoulders, thus bleeding they put him in a sugar cask swarming with cockroaches, cover him with a blanket, and leave him there to glut the vermin with his blood.” BLECH.

At the end of the War of Spanish Succession, 36,000 sailors for the British navy found themselves out of work. They flooded the general maritime workforce, and pay for honest work was cut nearly in half. Although there was not an immediate spike in piracy, it slowly crescendoed into the Golden Age of Piracy, with about 2,000 pirates roaming the seas. At the close of the Golden Age, writer Charles Johnson blamed Spanish influences in the West Indies for the uptick. They were too ready to turn a profit, he wrote, and gave out commissions for privateering without discretion. (translation: bloody foreigners.)

The Johnson Problem

The title page of Captain Charles Johnson's General History of Pirates reads like an old-fashioned movie poster: "Their first Rise and Settlement in the Island of Providence, to the present Time. With the remarkable Actions and Adventures of the two Female Pyrates MARY READ and ANNE BONNY". The book itself is a conundrum all historians must confront while covering piracy. It is one of the earliest sources that presents a collection of fairly reasonable information, but the accuracy is notoriously spotty. After 300 years, we still don't know with absolute certainty who was behind the pen name Charles Johnson (an older theory says he was Robinson Crusoe author Daniel Defoe; a newer and more likely theory is that he was writer/publisher Nathaniel Mist). The book is so hit-or-miss, historian David Moore says any claim Johnson makes has to be taken with "a hogshead of salt". And yet, General History is still the source. Everyone must pay homage — and then double-check every word.

Gold Rush

In reality, the spike in piracy was probably a combination of sailors out of work, privateers losing their commissions but wanting to keep their lifestyle, and the chance - however small - of making it big. In July 1715, 10 Spanish ships wrecked across 40 miles of Florida reef. A thousand men drowned, and a fabulous amount of silver coins and bullion were left behind in the wrecks. This sparked a maritime gold rush. Henry Jennings and his crew absconded with 270,000 pieces of eight after raiding the Spanish in the area. Operating across the Atlantic, Black Sam Bellamy robbed at least 53 ships in one year.

The stories began to echo the old buccaneer successes as the island New Providence became a hive for piracy; in a 1740 history of Jamaica, Charles Leslie wrote that this new wave of pirates, "had such surprising success as will perhaps scarce gain belief in succeeding ages."

Beginning of the End

Pirates made seafaring a risky business venture; in 1717 a group of Bristol merchants wrote the king, appealing for meaningful pirate suppression and proposing that former privateer Woodes Rogers be sent to New Providence to clean house. The British navy was not only woefully outnumbered, they were also bogged down (sometimes literally) by their enormous ships. Admiral Edward Vernon wrote that sending a lumbering navy vessel after a pirate was like sending, "a cow after a hare". In 1715 and 1716, the navy captured zero pirate ships. In 1717, that number was upped to one. On September 5, 1717, George I issued an offer of pardon, commonly known as the "Act of Grace". In exchange for a full pardon for past acts of piracy, the reformed had to:

Give up piracy by January 5, 1718 and

Turn themselves in to the proper authorities by September 5, 1718.

The day the pardon expired, the government would offer a reward for still-active pirates; the bounty on the head of a captain was £100 (about $13,000 in today's currency). If a crew member delivered their commander, the reward would be £200. The offer of pardon was widely published -- nailed up in the most public places, and would have been read aloud in churches. Some pirates quit while they were ahead, but others decided to test their luck a bit further.

If British merchants were perturbed by piracy, the impacts would have been closer to home for American colonists. For one thing, piracy was happening in their waters, off their shores. The larger ports on the east coast (New York, Philadelphia, Charleston) had a more metropolitan buzz to them, but trade interruption feels more urgent when a ship does not come in every day — or even every week. Virginia at least had the Chesapeake Bay, which was rich with oysters and served as a trade pathway to the Atlantic. In South Carolina, colonists accumulated wealth through shipping and successful rice crops.

Pyrite in the Rough

And then there was North Carolina. Called "a valley of humility between two mountains of conceit", she was the red-headed stepchild of the southern colonies. Where Charleston had a deepwater port and relatively easy sailing, North Carolina had a "vast chain of sandbanks so very shallow and shifting that sloops drawing only five foot water run great risk in crossing them" and a 60 mile stretch of shallow sound between ocean and mainland. After the sound, there were miles of tangled swampland to contend with, curtaining off inland settlements from the outside world and each other. In earlier years of the colony, agreements between the king, the proprietors, and settlers were markedly optimistic, outlining how they would divide the gold and precious gems they found, and setting high expectations for cash crops like silk and rice. Instead, they found finicky land better suited for growing watermelon, maize, and figs. Hog and hominy (corn, crushed by mortar because there were too few mills in the colony) were dietary staples, and pigs roamed the woods, distinct notching patterns in their ears marking ownership. Crops failed with alarming regularity.

North Carolina offered a few deal sweeteners to attract settlers to tame and fill the land. As of 1707, inhabitants could not be pursued for personal debts for their first five years of occupation. North Carolinians were also guaranteed freedom to worship per the dictates of their own conscience. In a time when church and government were intimately connected, even Quakers could hold positions of authority in both the vestry and General Assembly. These policies — and the difficult-to-access backwater settlements — meant newcomers ranged from garden variety European settlers arriving with stars in their eyes, to a large population of religious dissenters fleeing from the strict Anglican adherence required in other colonies, to criminals looking for a haven.

For years, those who came to North Carolina enjoyed being out of reach from whatever it was they left behind. In 1771 a Moravian minister wrote sourly that North Carolina's general public, "appear to me like Aesop's crow which inflated itself with other bird's feathers … They have Moravian, Quaker, Separatist, Dunkard principles, know everything and know nothing, look down on others, belong to no one, and spurn others."

This rough-around-the-center patchwork of people worked to settle the land. They heard new sounds (sometimes confusing the call of a bullfrog with a cow lowing her distress), saw hummingbirds for the first time (Lawson: "the miracle of all our wing'd animals; he is feather'd as a bird, and gets his living as the bees"), tried new delicacies like catfish, and learned the hard way that beavers should not be domesticated (they were "very mischievous in spoiling orchards...and blocking up your doors in the night").

Remains of a fireplace thought to have warmed John Lawson’s house.

Governor Edward Hyde wrote in 1712 that the people were "naturally loose and wicked, obstinate and rebellious, crafty and deceitful and study to invent slander on one another." It was not unusual for a governor of North Carolina to be at odds with the people in the colony — before Hyde, they had successfully ousted governors Jenkins, Miller, Eastchurch, Sothel, and Glover. Although it's easy to imagine these years looking like Colonial Williamsburg (with tidy boxwood hedges and obvious English influence), a better picture is the Wild West, but with swampland.

Picking Sides

In North Carolina, there were two main political factions: Proprietary men (men with stronger ties to the proprietors, more ready to work the system and possibly gain land and/or titles), and dissenters (the sometimes rougher, fiercely independent group, backed by strong Quaker support). Both sides tried to stack the Assembly, which was filled with men who were elected (not appointed), in their favor. Those tensions came to their natural conclusion in Cary's Rebellion, a series of skirmishes seeking to unseat Governor Hyde and replace him with more sympathetic Thomas Cary. Edward Mosley — lawyer, landowner, and eternal contrarian — did not seem to have any difficulty choosing a side. In fact, stolid government man Thomas Pollock wrote that he was, "the chief contriver and carrier-on of Colonel Cary's rebellion". Pollock himself sheltered the governor's men, and had cannonballs bounced off his roof for his trouble.

Before Hyde was comfortably established as governor, North Carolinians' scores to settle with each other went on the back burner as they found themselves in the midst of a years-long war.

The Tuscarora War started when a misunderstanding collided with grievances left unaddressed for too long, and it was bitter from its first day. On September 22, 1711, entire families were killed in coordinated attacks across North Carolina, pregnant women killed and babies ripped from the womb (historian David LaVerre notes that it was unusual for warriors to attack a woman at all, and this was probably a nod to the mistreatment of indigenous women). When the attacks fizzled out two days later, some settlers, too afraid to venture out, left their dead in the fields.

Aftershocks

Over three and a half years, hundreds of settlers and thousands of Native Americans died. All sense of security as something they could take for granted was shattered, for both sides. For the better part of three years, North Carolina had been struggling to subsist, unable to export many goods. North Carolina begged Virginia for assistance (after all, they had stepped in to resolve Cary's Rebellion); Virginia's Governor Spotswood responded mostly with snide, paternal letters, while South Carolina sent aid with strings attached. Reverend Urmston feared his family would starve; his colleague feared he had grown lazy and neglected baptisms. Abject misery is a common theme in government letters of the time describing the state of the colony. Pollock conservatively estimated the colony incurred £16,000 during the war. For years afterwards, the courts arranged new homes or apprenticeships for those orphaned by the conflict. At the close of the Tuscarora War, a particularly bad round of yellow fever struck the colony, killing many colonists, including Governor Hyde. Slowly recovering balance after reeling from misfortune, the colony was still stretched thin when Blackbeard set foot in Bath Town.

Bath (the small one)

Walk Bath; start at the Historic Site. For a couple of bucks, you can take a tour of the old homes in town. For free, you can check out some cool gravestones out back of the Palmer-Marsh house, and visit St. Thomas, the oldest church structure in the state.

Historic site manager Laura Rogers notes that today, most visitors approach Bath via two-lane highway, from the west. With no proper roads to connect settlements in 1718, travel and the first sight of Bath would have been by water. When famed evangelist George Whitfield made the rounds in North Carolina, it was notable that he could travel between New Bern and Bath in only a day; some speculated that the Divine must have been at work to accomplish such a feat. Whitfield's trip to Bath did not go well. He left in a huff, and (according to local legend) shook the dust of the town off his feet and cursed it, an explanation for why it never grew into anything more than a quiet, charming riverside hamlet. In all likelihood, what kept Bath from expanding was the difficulty of trading at scale. Because of the shallow sounds, larger merchant ships were forced to unload onto smaller boats waiting at Ocracoke Inlet, and those smaller boats transported goods back and forth.

An aside: When it comes to the Whitfield curse, Rogers is (rightly) quick to note, "It's really tough to document a lot of that that stuff.” Which begs the question, what would a documented curse look like? "Deare diary, today I curs'd the people of Bath-Towne…"

At the time of Cary's Rebellion, there were around nine houses in Bath, with a few more heads of household. Most would have lived in modest, one-or-two room homes, which was standard for Carolinians at the time. Wealthier individuals went on to build two-story structures with extravagances like double chimneys, and planters (including Governor Eden) lived outside of Bath proper on Bath Town Creek, boating in to conduct business. The trades in town covered the basics, and (if you were an optimist like Lawson), you would say the place was brimming with potential. Undoubtedly, that optimism was worn thin by 1718, and its people were more ready to welcome a pirate and his winnings to the local economy.

Conclusion

November 11, 1718

The Worsley children and servant had perhaps concocted their kidnapping story out of kindness, but a bloody, costly three year war had been sparked by little more. After handing down their sentence, the governor's council immediately dispatched a messenger to Tuscarora leader Tom Blount to explain what had happened and offer a reward for Pompey, if they happened to encounter him — dead or alive. The following summer Mary (the Worsley daughter) was fined £10 for her part in the plot.

In 1721, eleven years after starting his lonely and arduous mission, Reverend Urmston quit North Carolina with £138 uncollected pay and a damaged reputation. He told no one that he was leaving, Governor Charles Eden wrote with some irritation, except for dissenter Edward Moseley.

This was the world Blackbeard lived in as an adult, one with shifting loyalties and precarious peace; a world that could test the patience of a preacher to its breaking point in a matter of years. But what surroundings was he born into?

That is a more complicated question than you might imagine.

If you'd like to learn more on your own, check out these free resources:

Read the memoir/history written by Alexandre Exquemelin, including accounts of L'Olonnais's exploits

(fair warning, some stories are pretty gnarly)

Peruse images of John Lawson’s botany collection, gathered for London apothecary James Petiver

(apparently still in the British Museum's collection!).

Have feedback, questions, or flattery?

Feel free to reach out here.

If you’d like to support Long Way Around, please consider forwarding to a friend who you think will enjoy the series!

NOTES

(a quick disclaimer: I had grand intentions of only putting out polished, MLA styled end notes…and then I spent two weeks leading up to publication with spotty WiFi, lamenting my decision to keep everything on GoogleDocs. so these are mostly MLA style, with an exception of some links, because I’m behind and still digging myself out of a hole. If you’re worked up about formatting for linked info…please don’t tell me.)

The concept for this installment owes much to Genevieve Foster's World books starting with Augustus Caesar's World, and the author owes much to her for showing that one can bring warmth and plain language to history, and still have something worth reading.

home of Thomas Pollock: NC Council. Minutes of the North Carolina Governor's Council, 11/4/1718. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 313-4. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0169 Retrieved 7/20/20.

Thomas Worsley, a planter: Butler, Lindley S. "North Carolina 1718: The Year of the Pirates." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 134.

The whole kidnapping was a "villainous confederacy": NC Council. Minutes of the North Carolina Governor's Council, 11/11/1718. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 315. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0171 . Retrieved 7/20/20

£500: NC Council. Minutes of the North Carolina Governor's Council, 11/11/1718. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 315. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0171 . Retrieved 7/20/20

"39 lashes": The whole kidnapping was a "villainous confederacy": NC Council. Minutes of the North Carolina Governor's Council, 11/11/1718. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 315. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0171 . Retrieved 7/20/20

one of very few officially-sanctioned ministers:

stretch to make ends meet: Urmston, John. Quoted in LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2013. p. 10

"seduced by Quakerism": Eden, Charles. Letter to Secretary for the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, 10/8/1717. State Archives Microfilm, British Records, SPG/A/10

Ben Franklin's older brother: p. 19

27 consecutive years of war in India:

Alexi tortured to the point of death:

descendants of the Maya: Gosner, Kevin. "Historical Perspectives on Maya Resistance: The Tzeltal Revolt of 1712." Indigenous Revolts on Chiapas and the Andean Highlands, Kevin Gosner and Arij Ouweneen. CEDLA, 1996.

Under Oliver Cromwell, England tried to claim Hispaniola: Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 91

Sir Francis Drake: Dolin, Eric Jay. Black Flags, Blue Waters. New York City, Liveright Publishing Corp, 2018. p. 8-9

ushered in a flood: Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 155

John Lawson wrote worriedly in 1712: Lawson, John. “A New Voyage to Carolina.” John Lawson, 1674-1711. A New Voyage to Carolina. Academic Affairs Library, UNC-Chapel Hill , 2001, docsouth.unc.edu/nc/lawson/lawson.html. p. iii/iv

Anne was known for her ill health, poor eyesight:

divine right, and a tenuous relationship:

death warrant was signed and sealed by Oliver Cromwell:

dodging partisanship from both sides:

Coralana, after the latin version of his name: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/heath.asp and https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/introduction-colonial-north

land was divided between eight Englishmen who had been loyal:

could sell off parcels of land:

"a cauldron where the blood": Thornton, A.P. The Modyfords and Morgan, Jamaican Historical Review Vol. II, 1952. p. 37. Quoted in Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 89

people of desperate fortunes: Leslie, Charles. A New History of Jamaica. Quoted in Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 91

rescued a convicted pirate: Rediker, Marcus. Villains of All Nations. Boston, Beacon Press, 2004. p.11

began as scavengers: Dolin, Eric Jay. Black Flags, Blue Waters. New York City, Liveright Publishing Corp, 2018. p. 19

Spanish escalated attempts: Exquemelin, Alexandre. Buccaneers of America. Edited by William Swan Stallybrass. London, George Routledge & Sons Ltd, 1924. p. 76

Jean-David Nau alias François L'Ollanais: Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 94

escaped death at the hands of the Spanish: Exquemelin, Alexandre. Buccaneers of America. Edited by William Swan Stallybrass. London, George Routledge & Sons Ltd, 1924. p. 82-86

sacked Gibraltar: Exquemelin, Alexandre. Buccaneers of America. Edited by William Swan Stallybrass. London, George Routledge & Sons Ltd, 1924. p. 98

gaining 30,000 pieces: Exquemelin, Alexandre. Buccaneers of America. Edited by William Swan Stallybrass. London, George Routledge & Sons Ltd, 1924. p. 99

Tortuga, where buccaneers would go to replenish their supplies:

Exquemelin, Alexandre. Buccaneers of America. Edited by William Swan Stallybrass. London, George Routledge & Sons Ltd, 1924. p. 101

and

Exquemelin, Alexandre. Buccaneers of America. Edited by William Swan Stallybrass. London, George Routledge & Sons Ltd, 1924. p. 44-45

“with great liberality, giving themselves freely": Exquemelin, Alexandre. Buccaneers of America. Edited by William Swan Stallybrass. London, George Routledge & Sons Ltd, 1924. p. 44-45

smolder for a month: Exquemelin, Alexandre. Buccaneers of America. Edited by William Swan Stallybrass. London, George Routledge & Sons Ltd, 1924. p. 208 and 210.

Europe sent out manufactured goods like cloth, porcelain: Goodall, Jamie L.H. Pirates of the Chesapeake Bay. The History Press, Charleston, 2020. p. 46

planting, cultivating, and harvesting sugar cane: LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2013. p. 97

need on a voyage in his sea chest: Farrell, Erik et. al "Message in a Breech Block." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 244

clothing (distinctives: shirts, : Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998. p. 34

Most common sailor's quarters were in the forecastle: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998. p. 85-6

filled with chests, and hammocks were slung between beams: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998. p. 86

air would grow close: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998 p. 85-6

a standard ration was one pound of meat, one pound of bread: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998. p. 87

other fixings: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998 p. 87

three to five men at a time: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998. p. 87

supplemented their supplies with fresh local food: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998. p. 89

flamingo tongues, albatross, tortoise: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998. p. 89-90

"parboiled and fried with onions is pretty good eating": Barlow, Edward. Journal of His Life at Sea, edited by B. Lubbock, p. 220. Quoted in Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998.

rhythm of four hour watches, with an occasional two-hour: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998. p. 70

maintenance (caulking, scraping, scrubbing: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998. p. 76

"Sea-men are as it were a third sort": Flavel, John. Navigation Spiritualized: Or, a New Compass for Sea-Men, 1682. Introduction A3. Quoted in Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. p. 129

3-5% chance of wrecking: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998. p. 110

"storm-raisers": Bassett, Fletcher. Legends and Superstitions of the Sea and Sailors. Belford, Clarke & Co., Chicago, 1885. p. 449

scurvy, "bloody flux" (dysentery), malaria, and "ship fever": Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998. p. 133-136

"feeling his pulses when he is half dead": Barlow, Edward. Journal of his Life at Sea. Edited by Lubbock, p. 213-4. Quoted in Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998. p. 138

deducting three day's wages: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998. p. 135

having a thief run a gauntlet composed of his shipmates: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998. p. 152

keel-hauling, dragging a man under:

court systems were unfriendly: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998. p. 167

could involve a jury of the misdoer's peers, and a vote: Johnson, Charles. “A General History of Pirates, Second Edition.” T. Warner, London, 1724, p. 230. Via Project Gutenberg, 25 Aug. 2012, www.gutenberg.org/files/40580/40580-h/40580-h.htm.

"There is thin commons, low wages" Johnson, Charles. “A General History of Pirates, Second Edition.” T. Warner, London, 1724, p. 272. Via Project Gutenberg, 25 Aug. 2012, www.gutenberg.org/files/40580/40580-h/40580-h.htm.

first come, first serve: Rediker, Marcus. Villains of All Nations. Boston, Beacon Press, 2004. p.65

elected by a simple majority: Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 164

and

Johnson, Charles. “A General History of Pirates, Second Edition.” T. Warner, London, 1724, p. 230-232. Via Project Gutenberg, 25 Aug. 2012, www.gutenberg.org/files/40580/40580-h/40580-h.htm.

deposed or "turn'd before the mast": Rediker, Marcus. Villains of All Nations. Boston, Beacon Press, 2004. p. 69

only unquestionable in the heat of battle: Rediker, Marcus. Villains of All Nations. Boston, Beacon Press, 2004. p. 65

not just a carefree thief-in-chief: Pointed out in conversation by AJ Drake, historian at Bath Historic Site

all over the world: La Nouvelle Trompeuse (Boston 1684) included men from the British Isles, Holland, France, Sweden, Portugal, Spain, New England, plus Black and indigenous people from the Caribbean. Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars, New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 100

quartermaster (distributer of prize money: Rediker, Marcus. Villains of All Nations. Boston, Beacon Press, 2004. p. 67

settled matters such as deciding their course, electing leadership, and resolving disputes: Rediker, Marcus. Villains of All Nations. Boston, Beacon Press, 2004. p. 68

Pay was in proportion to contribution: Rediker, Marcus. Villains of All Nations. Boston, Beacon Press, 2004. p. 70

the average man got one full share: Rediker, Marcus. Villains of All Nations. Boston, Beacon Press, 2004. p. 70

captain might get one and a half or two shares: Rediker, Marcus. Villains of All Nations. Boston, Beacon Press, 2004. p. 70

shallow draft sloops: Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 162

might have 10 guns, and a maximum of about 100 men: Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 162

large prizes into men-of-war: Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 163

main trade routes from New England to Gambia: Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 100

anti-national: Rediker, Marcus. Villains of All Nations. Boston, Beacon Press, 2004. p. 8

key elements of a pirate flag: Rediker, Marcus. Villains of All Nations. Boston, Beacon Press, 2004. p. 98

most merchant captains realized fleeing: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998. p.14

pirates would corral the merchant crew into one area: Exquemelin, Alexandre. Buccaneers of America. Edited by William Swan Stallybrass. London, George Routledge & Sons Ltd, 1924. p. 61

and

Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 177-8

inquiring: Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p.176

Usually, the pirates released their victims with little extra trouble: Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 175

destroyed a ship with meagre provocation: See the case of the Protestant Caesar

avenged a captain's mistreatment: Betagh, A Voyage Round the World, p. 78. Quoted in Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p.176

tortured a crew member to extract: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998. p. 122

the most common tactic...woolding: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. London, Random House, 1998. p. 123

36,000 sailors: Rediker, Marcus. Villains of All Nations. Boston, Beacon Press, 2004. p. 23

nearly in half: Rediker, Marcus. Villains of All Nations. Boston, Beacon Press, 2004. p. 23

2,000 pirates roaming the seas: Rediker, Marcus. Villains of All Nations. Boston, Beacon Press, 2004. p. 29

blamed the Spanish influences in the West Indies for the uptick: Johnson, Charles. “A General History of Pirates, Second Edition.” T. Warner, London, 1724, p. 26. Via Project Gutenberg, 25 Aug. 2012, www.gutenberg.org/files/40580/40580-h/40580-h.htm.

an older theory says he was Daniel Defoe: Moore, David D. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 150

he was writer/publisher Nathaniel Mist: Brooks, Baylus C. “‘Born in Jamaica, of Very Creditable Parents’ or ‘A Bristol Man Born’? Excavating the Real Edward Thache, ‘Blackbeard the Pirate.’” The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. 92, no. 3, 2015, pp. 235–277. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/44113270. Accessed 21 Sept. 2020.

a hogshead of salt: Moore, David D. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 149-150

July 1715, 10 Spanish ships wrecked across 40 miles of Florida reef: Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 160

A thousand men drowned: Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 160

silver coins and bullion: Wagner, Pieces of Eight, 1967. Chapter 4. Quoted in Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 160

absconded with 270,000 pieces of eight: Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 160

at least 53 ships: Goodall, Jamie L.H. Pirates of the Chesapeake Bay. The History Press, Charleston, 2020. p. 47

"had such surprising success: Leslie, Charles. A New History of Jamaica, p. 91, Quoted in Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 91

group of Bristol merchants wrote: "America and West Indies: July 1717, 17-31." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 29, 1716-1717. Ed. Cecil Headlam. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1930. 344-364. British History Online. Web. 12 September 2020. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol29/pp344-364.

"a cow after a hare": Vernon to Burchett, 11/7/1720, in Vernon Letter-Book, Jan.-Dec 1720. Quoted in Rediker, Marcus. Villains of All Nations. Boston, Beacon Press, 2004. p. 29

In 1715 and 1716, the navy captured zero pirate ships: Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 183

1717, that number was upped to one: Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 183

September 5, 1717, George I issued an offer of pardon: Johnson, Charles. “A General History of Pirates, Second Edition.” T. Warner, London, 1724, p. 33. Via Project Gutenberg, 25 Aug. 2012, www.gutenberg.org/files/40580/40580-h/40580-h.htm.

January 5: Johnson, Charles. “A General History of Pirates, Second Edition.” T. Warner, London, 1724, p. 34. Via Project Gutenberg, 25 Aug. 2012, www.gutenberg.org/files/40580/40580-h/40580-h.htm.

bounty on the head of a captain was £100: Johnson, Charles. “A General History of Pirates, Second Edition.” T. Warner, London, 1724, p. 34. Via Project Gutenberg, 25 Aug. 2012, www.gutenberg.org/files/40580/40580-h/40580-h.htm.

reward would be £200: Johnson, Charles. “A General History of Pirates, Second Edition.” T. Warner, London, 1724, p. 72. Via Project Gutenberg, 34 Aug. 2012, www.gutenberg.org/files/40580/40580-h/40580-h.htm.

$13,000 in today's currency: retrieved 9/21/20

nailed up in public places, and would have been read aloud in churches: Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 190

and

Johnson, Charles. “A General History of Pirates, Second Edition.” T. Warner, London, 1724, p. 80. Via Project Gutenberg, 25 Aug. 2012, www.gutenberg.org/files/40580/40580-h/40580-h.htm.

colonists accumulated wealth: LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2013. p. 97

"a valley of humility between two mountains of conceit":

"vast chain of sandbanks so very shallow": "America and West Indies: September 1721, 6-10." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 32, 1720-1721. Ed. Cecil Headlam. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1933. 403-451. British History Online. Web. 21 September 2020. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol32/pp403-451. Document 654.

60 miles: "America and West Indies: September 1721, 6-10." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 32, 1720-1721. Ed. Cecil Headlam. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1933. 403-451. British History Online. Web. 21 September 2020. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol32/pp403-451. Document 654.

miles of swampland to contend with, curtaining off inland settlements: Butler, Lindley S. "North Carolina 1718: The Year of the Pirates." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018.

outlining how they would divide the gold and precious gems: accessed 9/24/20

expectations of the colony producing silk: Williamson, Hugh. The History of North Carolina, Vol. I. Thomas Dobson, Philadelphia, 1812. p. 115 and 117

watermelon: LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2013. p. 43

maize: Lawson, John. “A New Voyage to Carolina.” John Lawson, 1674-1711. A New Voyage to Carolina. Academic Affairs Library, UNC-Chapel Hill , 2001, docsouth.unc.edu/nc/lawson/lawson.html. p. 76-7

figs: Williamson, Hugh. The History of North Carolina, Vol. I. Thomas Dobson, Philadelphia, 1812. p. 115 and 117

Hog and hominy: (The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 1. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. xii. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007 https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.html/document/csr02-es01 . Retrieved 7/20/20.

notching patterns in their ears marking ownership: LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2013. p. 9-10

Crops failed with alarming regularity: LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2013. p. 9-10

for the first five years of occupation: NC General Assembly. Act of the NCGA concerning settlement 1707. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 674-75. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr01-0351. Retrieved 9/22/20

worship per the dictates: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/nc04.asp

hold positions of authority in the vestry and Assembly: NC General Assembly. An Act for Establishing the Church & Appointing Select Vestrys. 1715. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 210. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0106 . Retrieved 7/20/20, document number 105)

and

LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2013. p. 13

"appear to me like Aesop's crow: Soelle, George. Quoted in Iron, Charles F. "Evangelical Geographies of North Carolina." New Voyages to Carolina: Reinterpreting North Carolina History. Ed. Larry Tise and Jeffrey Crow. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2017. p.149

confuse the call of a bullfrog with a cow: Lawson, John. “A New Voyage to Carolina.” John Lawson, 1674-1711. A New Voyage to Carolina. Academic Affairs Library, UNC-Chapel Hill , 2001, docsouth.unc.edu/nc/lawson/lawson.html. p 132)

saw hummingbirds: Lawson, John. “A New Voyage to Carolina.” John Lawson, 1674-1711. A New Voyage to Carolina. Academic Affairs Library, UNC-Chapel Hill , 2001, docsouth.unc.edu/nc/lawson/lawson.html. p 145

tried new delicacies like catfish: Lawson, John. “A New Voyage to Carolina.” John Lawson, 1674-1711. A New Voyage to Carolina. Academic Affairs Library, UNC-Chapel Hill , 2001, docsouth.unc.edu/nc/lawson/lawson.html. p. 160

"very mischievous in spoiling orchards": Lawson, John. “A New Voyage to Carolina.” John Lawson, 1674-1711. A New Voyage to Carolina. Academic Affairs Library, UNC-Chapel Hill , 2001, docsouth.unc.edu/nc/lawson/lawson.html. p 120

"I never saw one acre of land managed as it ought to be": Lawson, John. “A New Voyage to Carolina.” John Lawson, 1674-1711. A New Voyage to Carolina. Academic Affairs Library, UNC-Chapel Hill , 2001, docsouth.unc.edu/nc/lawson/lawson.html. p. 75

"naturally loose and wicked": Hyde, Edward. Letter to Mr. Rainsford, 5/30/1712. Quoted in LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2013. p. 10.

successfully ousted governors Jenkins, Miller, Eastchurch, Sothel, and Glover: Saunders, William. Preface. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 1. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr01-es02 . Retrieved 9/3/20

two main political factions: LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2013. p. 9

"was the chief contriver and carrier-on of Colonel Cary's rebellion": Pollock, Thomas. Letter to Charles Craven, 2/20/1713. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 20. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0011 Retrieved 9/23/20.

Pollock himself sheltered the governor's men: LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2013. p. 14

September 22, 1711, entire families were killed: LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2013. p. 69-71

pregnant women killed and babies ripped from the womb: LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2013. p. 71

it was unusual for warriors to attack a woman at all: LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2013. p. 71

left the dead in the fields: LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2013. p. 72

hundreds of settlers and thousands of native Americans: LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2013. p. 185

North Carolina begged Virginia for assistance: NC Governor's Council, NCGA. Memorial concerning aid from Virginia, 1712. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 837-8. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr01-0449 Retrieved 9/23/20.

and

Pollock, Thomas. Letter to Alexander Spotswood, 1/15/1713. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 4-5. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0002 Retrieved 9/23/20.

snide paternal letters: Spotswood, Alexander. Letter to Thomas Pollock, 1/21/1713. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 5-6. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0003 Retrieved 9/23/20.

and

LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2013. p. 163

resolve Cary's rebellion: Saunders, William S. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 1. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. xxvii. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr01-es02 Retrieved 9/23/20.

feared his family would starve: Urmston, John. Letter to John Chamberlain, 5/30/1712. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 1. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 850-1. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr01-0455 Retrieved 9/22/20.

neglectful of baptisms: Rainford, Giles. Letter to John Chamberlain, 7/25/1712. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 1. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 857-860. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr01-0460 Retrieved 9/22/20.

debt incurred was £16,000: Quoted in LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2013. p. 185

For years afterwards, the courts arranged new homes or apprenticeships: Quoted in LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2013. p. 185

yellow fever, which killed many colonists: LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press, 2013. p. 137

notable that he could get from New Bern to Bath in only a day: Interview with Laura Rogers and AJ Drake of the Bath Historic Site

the Divine must have been at work: Interview with Laura Rogers and AJ Drake of the Bath Historic Site

larger merchant ships were forced to unload onto smaller boats waiting at Ocracoke Inlet: Interview with Laura Rogers and AJ Drake of the Bath Historic Site; AJ

around nine houses in Bath: Interview with Laura Rogers and AJ Drake of the Bath Historic Site; Laura

a few more heads of households: Interview with Laura Rogers and AJ Drake of the Bath Historic Site; AJ

modest, one or two room homes, which was standard for Carolinians at the time: Interview with Laura Rogers and AJ Drake of the Bath Historic Site; Laura

planters lived outside of Bath proper on Bath Town Creek, boating in to conduct business: Interview with Laura Rogers and AJ Drake of the Bath Historic Site

governor's council immediately dispatched a messenger: NC Council. Minutes of the North Carolina Governor's Council, 11/11/1718. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 159-160. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0171 . Retrieved 7/20/20

fined £10 for her part in the plot: General Court of NC. Minutes of the court, 7/28/1719 - 8/1/1719. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 358. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0185. Retrieved 9/24/20

£138 uncollected pay: retrieved 9/23/20

Governor Charles Eden wrote: Eden, Charles. Letter to David Humphreys, 4/12/1721. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 430. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0210 . Retrieved 7/20/20.

Foremastman: “Foremastman.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/foremastman. Accessed 23 Sep. 2020.

Rigging: “Rigging.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/rigging. Accessed 25 Sep. 2020.

Recipes:

Crackerhash: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. Random House, 1998 p. 88

Golden Era:

Rackham: Johnson, 150

Hornigold: Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 177

Asides:

Round Robin: Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775. Random House, 1998. Footnote for p. 177

Blooding and Sweating: Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. New York City, Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p.176