ISSUE № 8: DUST TO DUST

DUST TO DUST

Illustration by Kelsey Martin of Kettle Pot Paper.

A few notes: Most importantly, we are going to be covering hanging as a punishment for piracy in quite a bit of detail — if that's going to disturb your peace of mind, please feel free to skip this issue. Less importantly, Alexander Spotswood was technically lieutenant governor. But effectively, he was governor. To keep things simple, we'll just refer to him as Governor Spotswood.

In 1718, Alexander Spotswood had more immediate problems on his hands than piracy. As lieutenant governor of Virginia, he represented both the king and the absent actual governor, George Hamilton, Earl of Orkney — and Spotswood found himself cross-ways with a pack of powerful Virginians who were eager to sully his reputation with both of his bosses. In the midst of a contentious General Assembly session, most of his own council refused to attend his celebration of the king's birthday, opting instead to join a boozy bonfire hosted by members of the House of Burgesses. The Burgesses, elected by citizens of Virginia, had congregated in Williamsburg to tend legislative business for the first time since 1715, when a frustrated Spotswood dissolved the House. The returning hostile Burgesses had the majority of the governor's council on their side; when they joined forces with longtime Spotswood opponents and councilors Philip Ludwell and James Blair (who was also cofounder of the college of William & Mary), they presented a formidable challenge to the governor.

The Spotswoods were an enduring lot with a perhaps-inflated sense of the nobility of their struggle — Governor Spotswood had the family motto emblazoned on plates: Patior ut Potiar ("I endure that I may possess"), entwined with a thistle to represent difficulty, and a rose and laurel to represent love and honor — all qualities it seems the governor felt went under appreciated. That winter Spotswood wrote,

"For these thirty years past, no governor has longer escaped being vilified and aspersed here, and misrepresented at home.”

It was into this fraught scene that Blackbeard's former quartermaster, William Howard, was hauled for trial. Official charges had to do with Howard knowingly practicing piracy beyond the king's pardon deadline — the motivating force was likely that Howard was getting too comfortable in Virginia, too close to falling back into his old ways and dragging her citizens down with him. Captain Ellis Brand (part of the navy's patrol to secure the east coast's waters) expected Williamsburg's first mayor and member of the local Vice-Admiralty Court, John Holloway, to prosecute. To everyone's surprise, Holloway was already on retainer for the pirates, reportedly won over with ounces of gold, gold from only goodness knows where. Holloway ended up quitting the Vice-Admiralty Court in a huff, but not before having Captain George Gordon and Lieutenant Robert Maynard (the other part of the local navy patrol) arrested for false imprisonment of his client.

William Howard escaped hanging when, just in the nick of time, word of a fresh pardon from the king arrived by ship. Still, his trial had yielded useful information. It became official knowledge that Blackbeard and his crew had been actively pirating beyond January 5, which would have made them ineligible for pardons under the Act of Grace. Around the time of the trial, Spotswood received word that Blackbeard and Stede Bonnet — who only months earlier had received pardons from North Carolina's government — were out pirating again. Spotswood and Captains Brand and Gordon began to consider how they could bring Blackbeard to heel. Brand, who had been keeping tabs on the situation since that summer, sent to one of the Carolina gentlemen who had written to Spotswood to complain about the pirate's doings (and how little the government in North Carolina was doing to constrain them) for a more full account. Meanwhile, concern in Virginia mounted. Spotswood's strength — and shield from criticism — was a relatively safe colony and humming economy. They did not want another flotilla of pirates near their shore — much less a city of them or an island stronghold, which would constitute what Spotswood called a "nest of pirates".

On November 17, 1718, two sloops departed Virginia with a month's worth of supplies and orders to "destroy some pirates". Since the navy's heavy ships could not navigate Carolina's washboard shallows, Spotswood himself paid to hire out two smaller sloops, the Jane and the Ranger. The navy provided most of the crew from the two patrol ships: 22 men aboard the Ranger and 32 aboard the Jane, all under the command of Lieutenant Maynard. Maynard was the oldest naval officer serving in the colonies at the time, and was given leeway to consult with their local Carolina pilots and make executive decisions (In general, sailors stuck with their ordinary crewmates, with sailors under Captain Brand's command placed aboard the Ranger, and sailors under Captain Gordon aboard the Jane). Latest intelligence was that Blackbeard would likely be at home in Bath, so while the ships approached by water, Captain Brand set out for Bath Town over land on November 21.

Afraid word would gallop from the Burgesses to Carolina, Governor Spotswood proposed to fortify rewards for captured pirates with extra funding from the Virginia treasury without revealing the plan to capture Blackbeard. They quickly drew up the bill, and it passed nemine contradicente, or without dissent. The same week that the pirate suppression squad left town, the House of Burgesses dragged out their session, doing just enough state business to justify being open, but fixating on mundane, fiddly tasks. The bell was missing from the Capitol clock — who removed it, and on whose authority? And what was the state of the furniture in the Capitol? James Blair was part of the mini-committee that made careful inventory. These matters took several days to sort out, between a steady drip of petitions and budgetary reviews. Many delegates, sensing that the serious work of the session was finished, went home.

On November 20, the Burgesses whipped out articles of complaint against Governor Spotswood to send to the king and within 24 hours the 37 out of 52 Burgesses still in town voted on them (after airing the complaints, the furniture inventory was presented, perhaps a little sheepishly). They whittled down the original list of 14 grievances to six, polishing the language until the document went from bitter flamethrower to grieved, even-handed report. The initial draft invoked a soiling of sacred rights, a governor who must be removed at all costs — a power vacuum many worthy patriots would have happily stepped into (fortunately, we know nothing of this sort of politics today). The de-fanged list of accusations involved Spotswood's fraught relationship with the Burgesses, an improper imposition of quit rents, and how the governor "lavishe[d] away the country's money" while building the Governor's Palace. About a week later, when Spotswood came to address the Burgesses before the close of the session, the bulk of his seething speech focused on the articles of complaint — but he did pause long enough to praise the group for their cooperation in passing the bill to reward pirate capture and to announce the strike team's mission in North Carolina, adding,

“I am pretty confident of soon destroying that wicked crew there, and by a letter received last night from thence I expect that notorious pirate Tach is seized.”

Governor Spotswood's expectations were correct. Days earlier, on information gathered from a passing sloop, Lieutenant Maynard and company found Blackbeard anchored off Ocracoke. The battle started and ended on the morning of November 22, beginning with Blackbeard shouting promises of no mercy across the water, reportedly calling the king's men cowardly puppies and summoning damnation for his enemies. The battle ended with Blackbeard decapitated, surrounded by the wreckage of 10 dead pirates, among them a quartermaster, gunner, boatswain, and a carpenter. Captain Brand later wrote that upwards of 20 sailors from the Pearl and Lyme were wounded; one historian writes that judging by their paybooks, the Pearl lost nine men, the Ranger lost two. Blackbeard's surviving comrades — the nine captured at Ocracoke (most of them wounded), plus six more suspected associates rounded up by Captain Brand in Bath — were transported to Virginia for trial.

Instead of fetching pirates from all over the British Empire back to England for trial in the High Court of Admiralty, Britain established Vice-Admiralty Courts, which could convene as needed anywhere in the empire. Vice-Admiralty Courts had the right to issue warrants and examine and try pirates with a jury usually made up of a local governor, members of his council, and some representatives of the Admiralty (a captain or two would do). Each step — from how the indictment was phrased to sentencing — was meant to broadcast the state's views on piracy to the curious public, which was drawn in by the spectacle of a pirate (or sixteen) on trial. “A pirate is called Hastis Human Generis [enemy of mankind]," one judge proclaimed in an opening address to the court, "With whom neither faith nor oath is to be kept. And in our law they are termed brutes, and beasts of prey."

At the beginning of a court session, they were to read aloud the proclamation establishing the Vice-Admiralty Courts and how they should be run, then swear each sitting judge in.

Next, prisoners were brought forward to the bar, a bannister that came up to about waist height where nervous hands could rest, separating the general room from officers of the court. The prisoners heard their indictment read aloud while holding up their left hands so the court could check for the telltale brand of a first-strike felon (M for manslaughter, T for anything else), usually seared into the fleshy hollow just below the thumb. Almost every pirate pleaded not guilty, arguing that they were "forced men" — otherwise upstanding sailors who had been forced into piracy after capture. Occasionally, this was true. Usually, the evidence produced in court was enough to show that the individuals at the bar had willingly taken up arms and actively participated in piracy. The court only had to prove one instance of piracy (basically: stealing on water, no dead or brutalized victims required) to get a conviction. Short of a pardon, a conviction meant a hanging, and the pirate forfeiting all his property. Local governors were far less generous with their pardon power when a pirate had accepted the Act of Grace, and then returned to their old ways. The best a freebooter on trial could hope for was confusion or delay; cagey prisoners asked for legal counsel, for written copies of their indictment, for an extra day to prepare their defense.

After the court examined its witnesses, pirates would have a chance to cross-examine (this led to a particularly testy exchange between members of Stede Bonnet's crew and one of their fellow mariners who had turned king's evidence). Having heard from the prosecution, the witnesses, and the defense, the courtroom emptied out to allow the judges to consider the evidence. After the board reached a decision by voting in order from least to most senior member, prisoners and onlookers returned to hear the judgement. Pressed up to the bar with the crush of a full courtroom pushing in to hear the verdict, a convicted pirate would hear some variation of,

"You, [the convicted group] are to go from hence to the place from whence you came, and from thence to the place of execution, where you shall be hanged by the neck 'til you are dead, dead, dead. And may God of His infinite mercy be merciful to every one of your souls."

A trial might last a day or two — maybe pushing past a week in unusual circumstances. Once condemned, pirates did not have long to prepare themselves for eternity. In the intervening days, there seems to have been some leniency in allowing visitors, particularly for prayer and exhortation. Boston preacher of famed Puritan stock, Cotton Mather, frequented the jail with missionary ferverency. He later wrote,

"Perhaps there is not that place upon the face of the earth where more pains are taken for the spiritual and eternal good of [the] condemned." Jail cells were cramped, afforded little privacy, and were not made for long term use; their occupants had varying levels of receptiveness to Mather's prayers, preachments, and gifts of "Books of Piety." Some were ashamed, others refused to show any sign of penitence, and still others used their time to plead for a pardon (Stede Bonnet seemed to accumulate sympathy from the ladies in Charleston, as well as from his captor, Captain Rhett). One batch of pirates was allowed to dictate letters home the day before execution — one of the men wrote to his mother,

"The news of my being under a sentence of death I believe is very sinking and dreadful to you. I pray that God will support you under your sorrows and sanctify them to you." He also asked his brother to care for their mother in her old age and his absence. Another man asked his brother to break the news to his wife and four children, adding, "I pray God to be a husband to my dear wife, and a father to my dear children; and that she may bring them up in the fear of God; and that she and they together may be forever happy in Heaven." The shadow of the gallows seemed to stretch long, even into eternity.

An aside: "Why, I have been guilty of all the sins in the world!" John Brown of Jamaica told Cotton Mather. “I know not where to begin. I may begin with gaming. No, whoring. That led on to gaming; and gaming led on to drinking; and drinking to lying, and swearing, and cursing, and all that is bad; and so to thieving; and so to this!"

Local governments viewed pirate hangings as useful public demonstrations, a cautionary tale with a painful end. The public affair started with a grim walk (or sometimes cart ride) from imprisonment to the place of execution. Mather walked alongside Black Sam Bellamy's crew on their procession and recorded their distress — in one case, what weighed most heavily on the marching man's mind was his parents; another replayed his gradual decline into piracy, a liturgy of deepening regrets. Although it's said that all people find prayer when they are looking death in the eye, multiple pirates disclosed feelings of such utter ruin, they could not even look to God. Whether out of genuine penitence or hopes for a last-minute pardon (which were granted sometimes), some pirates approached the scaffold unwashed, unshaven, visibly sobered. Others were defiant to the end. When a former gunner of Blackbeard was executed in Nassau, two of his fellow pirates decked themselves out with long blue and red ribbons streaming from their necks, wrists, hats, and knees. In Massachusetts, lead mutineer William Fly strolled the path to execution with a nosegay in hand, breezily greeting onlookers. He bounded nimbly up the platform and, given a chance for a last word, refused to grant forgiveness to those who had wronged him and said that if ship's masters did not want to end up like his former captain (murdered), they should treat their sailors well. Still, onlookers noted, "in the midst of his affected bravery, a very sensible trembling attended him; his hands and his knees were plainly seen to tremble."

An aside: The gunner, William Cunningham, and the rest of the pirates involved in this trial were actually rounded up by Benjamin Hornigold - former pirate captain turned pirate hunter. We're sure this made Hornigold an imminently popular fellow.

In the moments leading up to the drop, some sang psalms in their native tongue, some sought strong drink, some exhorted onlookers not to follow their wicked path, one kicked off his shoes, one swore a blue streak. "Never was there a more doleful sight in all this land," wrote Mather, "than while they were standing on the stage, waiting for the stopping of their breath, and the flying of their souls into the eternal world. And oh! How awful the noise of their dying moans!" During the Golden Age of Piracy, the most hopeful prognosis the condemned could expect was just a few minutes of struggling for breath, coarse rope pressing into the flesh around the neck. Later years would bring the grim mercy of the hangman's knot and a chart to calculate a drop designed to snap the neck and expel life more efficiently. In 1718, the amount of pain you experienced before expiring depended entirely on a length of rope and the abilities of the hangman. Plummeting too far could cause decapitation; if the rope was too short, strangulation demanded more agonizing minutes. After the drop, any pretences of bravery or penitence were crowded out by the immediate effects of the noose. Lungs struggled fruitlessly, blood pounded, trying to get to the brain, as the body sometimes writhed, expelling urine and feces as legs flailed. Even as the mind knew the all-but-certain fate, the body strived to stay alive. In 1774, an anatomy professor wrote,

An aside: South Carolina Chief Justice Trott also noted to the courtroom after the Bonnet crew was sentenced to death, “It cannot but be a very melancholy Spectacle to see so many Persons, in the Prime of their years, in perfect Health and Strength, dropping into the grave.”

"The man who is hanged suffers a great deal … For some time after a man is thrown over, he is sensible, and he is conscious that he is hanging." After up to 20 minutes, convulsions would still, the corpse as ugly as the hanging itself — a bluish face, at times with bloody ooze staining the mouth and nostrils, reddened eyes bulging, hands clenched, reeking of bodily fluids. At the Cunningham hangings in Nassau, the authorities draped a black flag behind the gallows, signifying that those who lived (and pirated, and interrupted Great Britain's trade routes) under the black flag would surely die by it, too.

Often hanged pirates were left in the lapping tide for a few days. To get more extended use from them, cadavers could also be slathered in tar and strung up in gibbets at busy waterways as a slowly-rotting warning.

After a Vice-Admiralty Court session concluded, the register was supposed to send records of the proceedings back to the High Court of Admiralty in England. Unfortunately, whether by fire, salt water, accident, or malice, no direct record exists for the trial of Blackbeard's crew. Because the pirates were extradited to Virginia, we can surmise that the trials happened in the Capitol building in Williamsburg — just across the hallway from the House of Burgesses. The rest of what we know about Blackbeard's crew after the battle of Ocracoke is collected from scraps, references in council minutes, letters, and logbook entries, all with dates so spread out, it suggests that the crew was split up into a few separate trials.

In late January, a month after the pirates arrived in Virginia, logbooks from the Pearl noted that two pirates faced morning executions at Hampton, and that they were hanged up in chains, along with Blackbeard's head. On February 14, 1719, Governor Spotswood wrote Lord Cartwright, one of North Carolina's Lord Proprietors, that the prisoners had been tried. A month later, he went to his council, seeking advice on whether or not to try the Black men captured at Ocracoke as pirates (the council said yes). By May, the four men, who during their trial delivered testimony that incriminated North Carolina secretary and chief justice Tobias Knight, could not be cross-examined regarding Knight's case, because they had already been executed.

What happened to the crew outside of the six recorded hangings? According to Johnson's General History, Samuel Odell (found aboard Blackbeard's ship in what appears to be a world record case of being in the wrong place at the wrong time) was acquitted. When yet another extension of the Act of Grace arrived just before execution, Israel Hands — one of Blackbeard's high-ranking officers turned king's witness — received a pardon. It seems unthinkable that a governor so determined to break up an insidious cabal and make an example of the pirates would allow for easy acquittals or pardons. And yet, years after the trial, names that match the captured crew started appearing in North Carolina records.

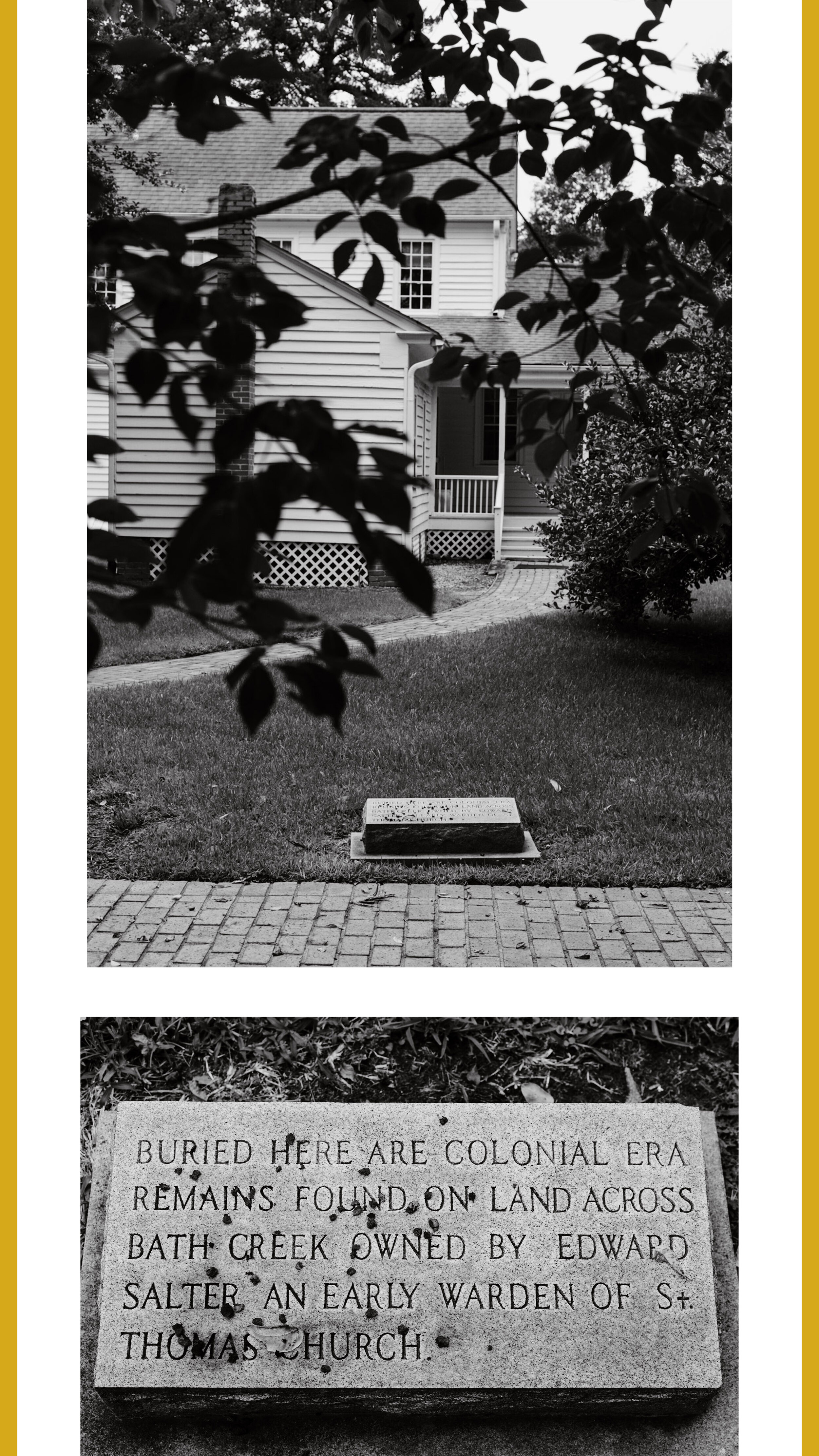

An aside: It took too many words to say this, but the presumed Salter grave was "unexpectedly discovered" when a giant bulldozer rolled over it and collapsed the grave during construction on the land.

Because family names tended to echo, it's impossible to say with complete certainty that these names are a direct match to Blackbeard's crew — but it is not unreasonable to dash a line between them in pencil. John Martin appears with land purchases in the Beaufort County deed book, and a James Robins surfaces in court records in 1719 after being caught in a compromising position with two women. Historian Kevin Duffus doggedly pursued these names in archives and courthouse basements; the name that made the biggest impact, both on the paper trail and on Duffus, was Edward Salter. A grave unexpectedly discovered on land that used to belong to Edward Salter led to a protracted court battle to transfer the remains from the state back to the Salter family (In Salter's will he wished for a decent burial and, Duffus said, "Being in a cardboard box on a shelf on Jones Street in downtown Raleigh was not what he had in mind."). When it was time to drive the remains from forensic examination in Washington, D.C., back to North Carolina for reinterment, Duffus was the man for the job. The skeleton's last voyage was in three carefully-packed boxes in the trunk of a Toyota Venza, driving south on I-95. St. Thomas (the oldest church in North Carolina, built in part with Salter funds) did not want to become a pirate attraction and insisted on a modest marker for the grave.

An aside: Decades earlier, Duffus had accidentally stuck his head in a grave while exploring a graveyard. After the incident, Duffus said, "I felt like I had this obligation. I had taken on some type of...debt, that had to be repaid, someday. I couldn't explain it. I mean, it was just a sense, I couldn't verbalize it, but I knew somehow I was obligated to that person. And the day that I watched Edward Salter's casket being lowered in the ground at St. Thomas's church in Bath, I suddenly felt relieved of that debt."

The aftereffects of the battle of Ocracoke rippled slowly, scratched into letters exchanged across the ocean. North Carolina's government, displeased with the high-handed way Governor Spotswood had intervened, insisted that the pirated goods carried off to Virginia ought to be returned to North Carolina to be tried and condemned. When their plea was rejected, they threatened Captain Brand with a lawsuit for trespassing into the Lords Proprietor's lands, purportedly gathering affidavits to prop up their case. On March 11, 1719, the Vice-Admiralty Court condemned the goods; since many were perishable, they were auctioned off for around £2,200. After covering expenses for the expedition, Spotswood sent the profits to England for safekeeping. As promised, the Virginia General Assembly delivered the reward for Blackbeard's captured crew, about £300 — roughly the same amount as Governor Eden's annual salary. Split between the crews of the Pearl and Lyme, a base share for a sailor who went on the mission was one pound, thirteen shillings, and sixpence — the more senior the officer, the more shares he received (the crew members who stayed behind only received seven shillings, sixpence). Both captains did not hoard their significant portions, instead distributing it amongst the sailors who had actually gone to Ocracoke, Captain Gordon doubling the share of Lieutenant Maynard, who also received a handsome bonus directly from Governor Spotswood and some of his council.

As time wore on, a base payment of one pound, thirteen shillings, and some odd pence did not seem like much for the sailors' valiant efforts, particularly to Lieutenant Maynard. As he and other crew members sought larger portions of the remaining bounty to the exclusion of their fellow crew members who held down the fort back in Virginia, pieces of his story came under scrutiny. In Maynard's petition, he represented that during the battle he boarded Blackbeard's sloop first, leading the charge into enemy territory. Maynard sourly noted in a letter written to his counterpart aboard HMS Phoenix (and later published in a London paper) that he was sent out with only "small arms" — no cannons — and characterized the Ranger as a bumbling part of the mission, leaving him to go after the pirates all by himself in the Jane. Maynard credited the calm day with being able to shoot away the pirate's jib and fore-halliard, causing Blackbeard to careen into grounding, admitted to his confidante, "I should never have taken him, if I had not got him in such a hole, whence he could not get out." Despite being in unfamiliar waters with less heavy-duty weaponry, Maynard boasted that the strike team killed a dozen pirates besides Blackbeard, and that they, "fought like heroes, sword in hand, and they kill'd every one of them that enter'd..." Maynard's account ended with beginning his triumphant return to Virginia, Blackbeard's head on his bowsprit.

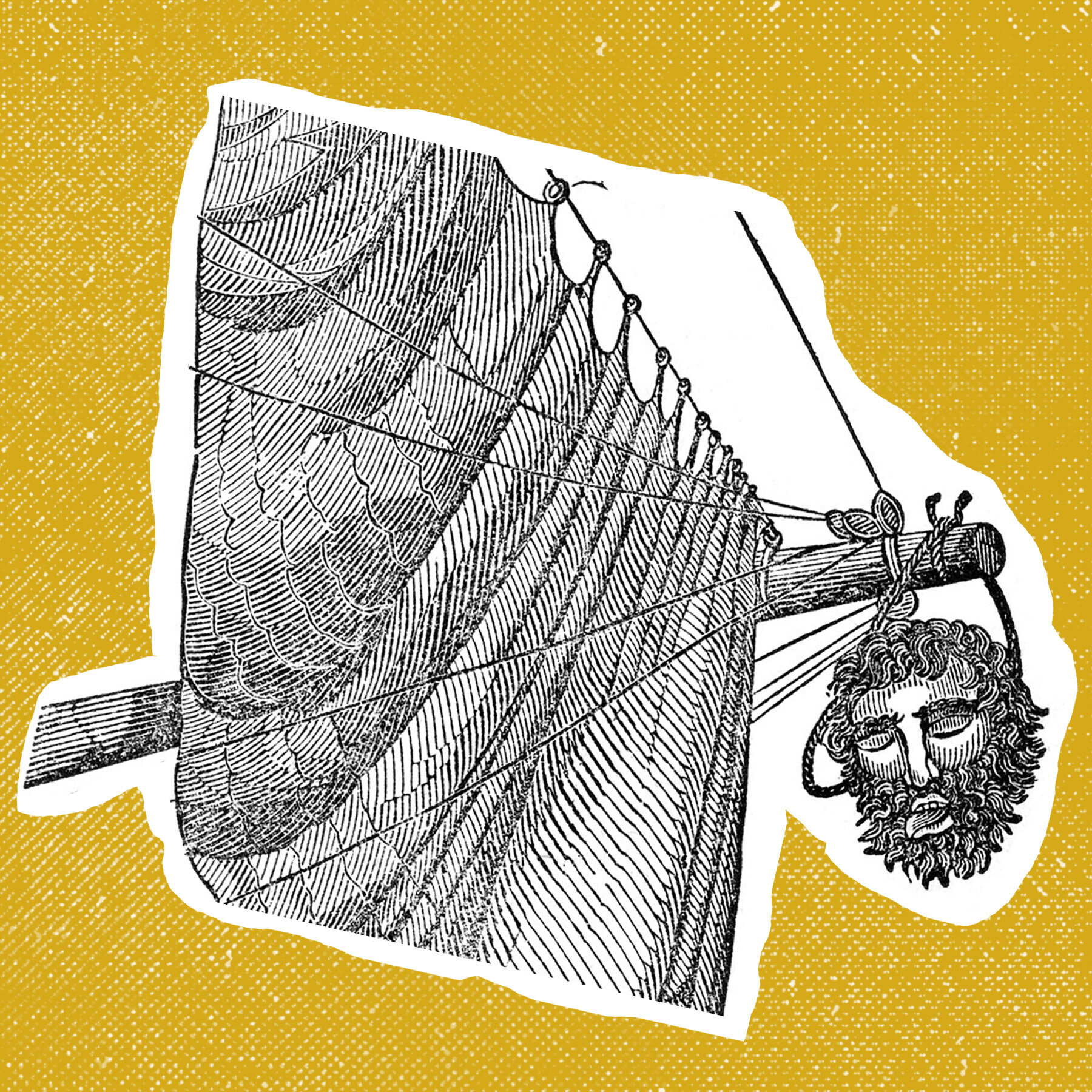

Illustration from The Pirate's Own Book, published in 1837. There's some discussion of whether or not Blackbeard's head actually decorated the bowsprit, but it's referenced enough in primary documents (and Maynard proved himself capable of such displays of heroics), it may well have happened. Pure speculation here: The way it's talked about suggests a less risky situation than a head dangling from the end of a rope. Perhaps a pike through the head, secured under the bowsprit — close to the ship, not far over water and out of reach.

Both Captain Brand and Captain Gordon's accounts of the battle cast the good lieutenant in a less heroic light. For one thing, the actual sailing was far from smooth. Captain Brand reported that Maynard had ordered the Ranger in first to go after the pirates, bringing the Jane into shallower waters after the Ranger got stuck, only to have the Jane also get stuck and have to struggle free, which allowed Blackbeard time to scramble an attempted escape and a devastating defense. When the Ranger was only a gunshot away from Blackbeard's ship, the pirates delivered a ruinous broadside, killing or wounding 21 men. Captain Gordon wrote that in the melee, one of the navy's men was actually killed by friendly fire. After finding himself outgunned and his men exposed, Maynard had most of his crew — including himself — go into hiding, leaving only a midshipman and a pilot on deck. When Blackbeard clambered onto the Jane's deck, rope in hand to tether his new prizes, the pilot signaled Lieutenant Maynard, who in turn sprung the trap, a flood of sailors reappearing from their hiding place belowdecks and swinging into battle with Blackbeard and crew. Captain Gordon wrote that within six minutes, Thatch was dead, and the battle was over. It's still a clever trick, but it's a far cry from the lieutenant, bold and true-hearted, leading the charge onto Blackbeard's ship for a battle of epic proportions.

After the battle, the navy men went ashore at Ocracoke to recuperate. While on land, they discovered about 140 bags of coco and 10 casks of sugar stockpiled under a tent. After spotting birds circling, they also found another dead pirate, his body caught in the reeds. Having found a similar stockpile in Tobias Knight's keeping, Captain Brand had Lieutenant Maynard bring the sloops in to Bath Town, and loaded them down with all the plunder connected with Thatch — coco, sugar, and six enslaved Black men.

Both Captain Brand and Captain Gordon said that Lieutenant Maynard received careful instructions to make sure that none of the pirate's plunder was distributed before reaching Virginia. The day after Maynard arrived, greeted with beautiful weather and triumphant nine-gun salutes ringing across the water, Captain Brand heard that the moment he had left the ships in Lieutenant Maynard's charge in Bath, Maynard took it upon himself to divide up part of the plunder, which reportedly included gold dust and plates. As commander-in-chief of the vessel, he was entitled to a three-eighths portion; Captain Gordon had it on good authority that Maynard's portion was worth about £90. Brand said that he did not know exactly how or to whom Maynard distributed the rest of the loose plunder, "tho I believe [it was] not to anybody's satisfaction but his own." At Brand's request, Captain Gordon questioned his lieutenant on the matter. In an answer jarringly impudent for the Royal Navy, Lieutenant Maynard replied that he would answer for himself directly to the Admiralty.

Lieutenant Maynard's petition and Captain Gordon's counter-petition wound their way up through the Admiralty, through the Treasury, and then went to the king's council. The king ordered that the profit from Blackbeard's auctioned goods be delivered to the High Court of Admiralty, and that the officers of the Pearl and Lyme receive their reward, distributed just like in the last war. Translation: Captain Gordon had won. Each and every sailor from the Pearl and Lyme would receive some part in the reward.

Lieutenant Maynard was not promoted for another 22 years. Captain Brand was an admiral by the time he died in 1759; Captain Gordon was mortally wounded by robbers while back in England in 1730. The last recorded trace of Blackbeard's former lieutenant Israel Hands placed him in London, begging for bread. Within five years of Blackbeard's death, North Carolina Governor Eden succumbed to yellow fever. His chief beneficiary was John Lovick, the colony's secretary whose home Edward Moseley and associates had broken into while searching for evidence of the governor's alleged collusion with pirates. After Eden's death, the council unanimously voted proprietary man Thomas Pollock back as interim governor. Moseley eventually regained his role as Speaker in North Carolina's House of Burgesses, then took his place on the governor's council, where he quickly became a divisive figure.

In May of 1720, both Virginia's Governor Spotswood and his council wrote to the Board of Trade that they had buried the hatchet, and any past complaints about each other should be ignored. By 1722, construction on the Governor's Palace was finally complete, a display of brick and marble and power, and Alexander Spotswood was replaced by Hugh Drysdale. When Spotswood was presented to the king a few years later, he made a point of writing to his cousin that the Duke of Newcastle told his majesty that, “No governor who had been abroad had acquitted himself so well of his Province as I had done.”

In Carolina, Edward Salter bought up considerable parcels of land, and his descendants took part in the Revolutionary War. The Howards and Salters (not to mention some Jacksons) settled on Ocracoke; both of the lines have offspring that are keepers of island lore. At the History Museum of Carteret County, a Martin descendant works in the archive, methodically mining reference books, maps, and letters to help others find pieces of their own history. And Blackbeard settled in as resident spook, blamed for every strange bump, flicker, and wail in the night. Many claim him as a distant relative or direct ancestor, few blame him for leading their forefathers to the noose. In a strange bit of lopsided justice, Blackbeard's story was stolen from him the moment he died — pilfered by Lieutenant Maynard in service of his ambitions, by the patrolling captains, by governors and their rivals, by the men who broke into Secretary Lovick's house, by generations of fisherman, and by tourism directors and ice cream sellers.

This is what keeps people coming back to Blackbeard — the chance to add a layer, or to peel one away; to grasp just one piece of the mirage. Story-spinners enjoy the shimmer and mist of it. Historians and archeologists, conservators and archivists are haunted by the gaps in the story. Lost letters and logbooks are like a ghost limb, an ache without a leg to stand on. The further you press in, the more the gaps open up. The haze of the unknown is a siren call, enveloping searchers like a lazy Saturday morning stupor, convincing them that five more minutes will do the trick. Just five more minutes of searching. Just one more rotation of the microfilm reel, just one more visit to yet another archive. Just one more, in the hopes of a new epilogue — or better yet, a transformed story. Just one more.

Hi, folks! Megan here. I'm stepping out from behind the "faceless narrator" act for just a moment to say thank you for sticking with both me and Long Way Around for eight whole issues! Truth be told, I'm not sure where things go from here (More long-term research that turns into longform content? Magazine work? Moving to England and joining the circus? Who knows!) — but I always know that this year will have a formative place in my personal history, one that I'm so thankful for. Getting to gather so many stories from across the centuries and relay them to you has been a privilege. If you'd like to stay in touch, my online home is thistleandsun.com, but you're more likely to see timely updates on my Instagram. Thank you again, and farewell for now!

More (free!) avenues for intellectual adventure:

Read the conversations between Cotton Mather and the pirates on their final walk.

Take an interactive virtual tour of the Capitol building in Williamsburg, reconstructed as it would have been when Blackbeard's crew faced their trials.

Read this brief snapshot of James Blair, nemesis of many Virginia governors.

Have feedback, questions, or flattery?

Feel free to reach out here.

NOTES

absent actual governor, George Hamilton, Earl of Orkney: Retrieved April 21, 2021

In the midst of a contentious General Assembly session: Journals of the House of Burgesses, 1712 - 1726. Richmond, VA, Virginia State Library, 1912. p. 37, just for starters.

refused to attend his celebration: Retrieved April 17, 2021

for the first time since 1715: Journals of the House of Burgesses, 1712 - 1726. Richmond, VA, Virginia State Library, 1912. p. xxxiv

link arms with council member Philip Ludwell: Ibid., p. xxxiv.

James Blair (who was also cofounder of the college of William & Mary): Retrieved April 21, 2021

Spotswood had the family motto emblazoned on plates: A Spotswood to John Spotswood, September 3, 1718 [Citation misplaced]

"For these thirty years past, no Governor...": Spotswood to Trade Board, December 22, 1718. Retrieved 11/23/20.

Official charges had to do with: Indictment of William Howard, October 29, 1718. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

Howard was getting too comfortable in Virginia: Spotswood to Craggs, July 28, 1721. Retrieved 1/22/20

expected Williamsburg's first mayor: Brand to Admiralty, April 8, 1719. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

reportedly won over with ounces of gold: Spotswood to Craggs July 28, 1721. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

quitting the Vice Admiralty Court in a huff: Brand to Admiralty, April 8, 1719. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

arrested for false imprisonment of his client: Spotswood to Craggs July 28, 1721. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

word of a fresh pardon from the king arrived by ship: Brand to Burchett, July 14, 1719. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

official knowledge that Blackbeard and his crew had been actively pirating beyond January 5th: Indictment of William Howard, October 29, 1718. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

Around the time of the trial, Spotswood received word that both Stede Bonnet and Blackbeard...local gentlemen about the government's inability to restrain them: Spotswood to Trade Board, December 22, 1718. Retrieved 11/23/20.

Spotswood and Captains Brand and Gordon: Ibid.

tabs on the situation since that summer: Brand to Burchett February 6 1718-19. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

complaining gentlemen: Ibid.

"nest of pirates": Spotswood to Trade Board, December 22, 1718. Retrieved 11/23/20.

On November 17, 1718: Lt. Maynard's logbook. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

destroy some pirates: Ibid.

Spotswood himself paid to hire out: Brand to Burchett February 6 1718-19. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

and

Calendar of Treasury Papers, Volume 5 (1714-1719), p. 467. Retrieved March 2021.

The navy provided most of the crew: Spotswood to Trade Board, December 22, 1718. Retrieved 11/23/20.

22 men aboard the Ranger, and 32 aboard the Jane: (Cooke, Arthur L. “British Newspaper Accounts of Blackbeard's Death.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 61, no. 3, 1953, pp. 304–307. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4245947. Accessed 8 June 2020)

under the command of Lieutenant Maynard: Brand to Burchett February 6 1718-19. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

oldest naval officer serving in the colonies: Dolin, Eric Jay. Black Flags, Blue Waters. New York City, Liveright Publishing Corp, 2018. p. 246

given leeway to consult with their local Carolina pilots and make executive decisions: Brand to Burchett February 6 1718-19. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

with their ordinary crewmates: Moore, David. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 181

Latest intelligence was that Blackbeard would likely be at home in Bath: Brand to Burchett February 6 1718-19. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

Afraid word would gallop from the Burgesses to Carolina: Spotswood to Trade Board, December 22, 1718. Retrieved 11/23/20.

Governor Spotswood proposed to fortify rewards: VA General Assembly Journals, Nov. 13, 21 1718

it passed nemine contradicente: Journals of the House of Burgesses, 1712 - 1726. Richmond, VA, Virginia State Library, 1912. p. 226

The same week the pirate suppression squad left town, the House of Burgesses dragged out their session: Ibid. p. 224 - 229

The bell was missing from the Capitol clock: Ibid., p. 224

James Blair was part of the mini-committee: Ibid., p. 226

session was finished, went home: Spotswood to Trade Board, December 22, 1718. Retrieved 11/23/20.

37 out of 52 Burgesses: Journals of the House of Burgesses, 1712 - 1726. Richmond, VA, Virginia State Library, 1912. p. xxxix and xxxiv.

voted on them within 24 hours: Ibid., p. 228-231

original list of 14 grievances to six: Ibid., p. 230-1

tailored the language: Ibid., p. 231

the bulk of his seathing speech focused on the articles of complaint: Ibid., p. 242

“I am pretty confident of soon destroying that wicked crew": Ibid., p. 244

Days earlier, on information gathered from a passing sloop: Brand to Burchett February 6 1718-19. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

beginning with Blackbeard shouting promises of no mercy across the water: Cooke, Arthur L. “British Newspaper Accounts of Blackbeard's Death.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 61, no. 3, 1953, pp. 304–307. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4245947. Accessed 8 June 2020 p. 305

Blackbeard reportedly calling the king's men: Ibid.

10 dead pirates: Brand to Burchett February 6 1718-19. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

Among them a gunner...: Johnson, Charles. A General History of Pirates. Second Ed., T. Warner, London, 1724, p. 90

nine more captured, most of them wounded: London Gazette, April 21-25 1719; Cooke, Arthur L. “British Newspaper Accounts of Blackbeard's Death.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 61, no. 3, 1953, pp. 304–307. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4245947. Accessed 8 June 2020

Captain Brand later wrote that upwards of 20 sailors from the Pearl and Lyme: Brand to Burchett February 6 1718-19. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

judging by their paybooks: Moore, David. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 181

transported to Virginia for trial: Brand to Burchett February 6 1718-19. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

Britain established Vice Admiralty Courts: The Tryals of Captain John Rackham, and Other Pirates. Jamaica, printed by Robert Baldwin, 1721, p. 41.

right to issue warrants, and examine and try pirates with a jury: Ibid., p. 42.

“A Pirate is called Hastis Human Generis": The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet and Other Pirates. London, printed for Benjamin Cowse, 1719, p. 3

while holding up their left hands: The Trials of Eight Persons Indicted for Piracy 1717, p. 1-2. Retrieved March 2021

and

Ten Persons Tried for Piracy at Nassau. December 9-10, 1718, retrieved March 2021.

and

Cross, Arthur Lyon. “The English Criminal Law and Benefit of Clergy during the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century.” The American Historical Review, vol. 22, no. 3, 1917, pp. 544–565. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1842649. Accessed 22 Apr. 2021.

M for manslaughter, or T for anything else: Cross, Arthur Lyon. “The English Criminal Law and Benefit of Clergy during the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century.” The American Historical Review, vol. 22, no. 3, 1917, pp. 544–565. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1842649. Accessed 22 Apr. 2021.

far less generous with their pardon power: 10 Persons Tried for Piracy at Nassau, The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet and Other Pirates. London, printed for Benjamin Cowse, 1719

legal counsel, for written copies: The Trials of Eight Persons Indicted for Piracy 1717, p. 3-4. Retrieved March 2021.

particularly testy exchange between members of Stede Bonnet's crew: The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet and Other Pirates. London, printed for Benjamin Cowse, 1719, p. 29.

courtroom emptied out to allow the judges to consider the evidence: Ibid., p. 43

voting in order from least to most senior member: The Tryals of Captain John Rackham, and Other Pirates. Jamaica, printed by Robert Baldwin, 1721, p. 42

"You, [the convicted group] are to go...": Ibid., p. 11-12

"Perhaps there is not that place upon the face of the earth": Mather, Cotton. Instructions to the living from the condition of the dead, p. 9. Retrieved February 2021.

Stede Bonnet seemed to accumulate sympathy from the ladies in town, as well as from his captor, Captain Rhett: Moss, Jeremy R. The Life and Tryals of the Gentleman Pirate, Major Stede Bonnet. Virginia Beach, koehlerbooks, 2020. p.168 and 174

"The news of my being under a sentence of death I believe is very sinking…": Mather, Cotton. Useful Remarks: An Essay Upon Remarkables in the Way of Wicked Men,, p. 40. Retrieved 2/7/21

"I pray God to be a husband to my dear wife": Ibid., p. 38.

from imprisonment to the place of execution: Mather, Cotton. Instructions to the living from the condition of the dead, p. 10-34. Retrieved February 2021.

recorded their distress: Mather, Cotton. Ibid., p. 9.

unwashed, unshaven, visibly sobered: Ten Persons Tried for Piracy at Nassau. December 9-10, 1718, retrieved March 2021.

long blue and red ribbons: Ibid.

strolled the path to execution with a nosegay in hand: Mather, Cotton. The Vial Poured Out Upon the Sea, p. 47. Retrieved 2/9/21.

"in the midst of his affected bravery": Ibid., p. 48.

one kicked off his shoes: Ten Persons Tried for Piracy at Nassau. December 9-10, 1718. Retrieved March 2021.

"Never was there a more doleful sight in all this land…": Mather, Cotton. Useful Remarks: An Essay Upon Remarkables in the Way of Wicked Men., p. 43. Retrieved 2/7/21

hangman's knot: Gruesome Practices of the Past, retrieved 4/12/21.

chart to calculate a drop: Rayes, Mahmoud et al. Hangman’s Fracture: A Historical and Biomechanical Perspective p. 205, retrieved 4/12/21

Plummeting too far could cause decapitation: Rayes, Mahmoud et al. Hangman’s Fracture: Ibid., p. 204

if the rope was too short, strangulation took longer: Ibid.

Lungs struggled fruitlessly, blood pounded…: Ibid.

writhed, legs kicking: Gatrell, V.A.C. The Hanging Tree: Execution and the English People 1770-1868: Execution and the English People, 1770-1868. Oxford University Press, 1994. p.45, 46, 54.

expelling urine and feces: Ibid., p.46

"The man who is hanged suffers: Ibid., p. 45-46

After up to 20 minutes: The Hanging Tree: Ibid., p. 48

a bluish face...: The Hanging Tree: Ibid., p. 46

authorities draped a black flag behind the gallows: Ten Persons Tried for Piracy at Nassau. December 9-10, 1718. Retrieved March 2021.

lapping tide for a few days: Cordingly, David. Under the Black Flag: The Romance and the Reality of Life Among the Pirates. Harcourt Brace & Company, 1997. p. 233

slathered in tar and strung up in gibbets: The Tryals of Captain John Rackham, and Other Pirates. Jamaica, printed by Robert Baldwin, 1721, p. 15.

and

Cordingly, David. Under the Black Flag: The Romance and the Reality of Life Among the Pirates. Harcourt Brace & Company, 1997. p. 227

the register was supposed to send records: The Tryals of Captain John Rackham, and Other Pirates. Jamaica, printed by Robert Baldwin, 1721, p. 42-43

a month after the pirates arrived in Virginia: Lieutenant Maynard's Logbook, entry dated January 19, 1719. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

executions at Hampton, and that they were hanged up in chains: Moore, David. "Captain Edward Thatch: A Brief Analysis of the Primary Source Documents Concerning the Notorious Blackbeard." The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. XCV, Number 2, April 2018. p. 183-4

February 14, 1719, Governor Spotswood wrote Lord Cartwright: Spotswood to Cartwright, February 14, 1719. Retrieved February 2021.

A month later, he went to his council, seeking advice: VA Council. Minutes of the Virginia Governor's Council, 3/11/1719. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 159-160. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0175 . Retrieved 7/20/20. p. 327

they had already been executed: NC Council. Minutes of the North Carolina Governor's Council, 5/27/1719. The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Ed. William L. Saunders. Vol. 2. Raleigh, N.C.: P. M. Hale, Printer to the State, 1886. 159-160. Documenting the American South. 2007. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. 27 November 2007. https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr02-0181 . Retrieved 7/20/20. p. 341

According to Johnson's General History: Johnson, Charles. A General History of Pirates. Second Ed., T. Warner, London, 1724, p. 90

and

Cordingly, David. Spanish Gold. Bloomsbury, 2011 p. 177.

Israel Hands...received a pardon: Johnson, Charles. A General History of Pirates. Second Ed., T. Warner, London, 1724, p. 90

John Martin appears with land purchases in the Beaufort County deed book: Bailey et al. "Legends of Black Beard and His Ties to Bath Town: A Study of Historical Events Using Genealogical Methodology." North Carolina Genealogical Society Journal, vol. 28 no. 3, 2002. p. 277

James Robins surfaces in court records: Duffus, Kevin. "The Last Days of Blackbeard the Pirate" 4th ed., Looking Glass Productions, Raleigh, 2014. p. 172

land that used to belong to Edward Salter: Duffus, Kevin. "The Last Days of Blackbeard the Pirate" 4th ed., Looking Glass Productions, Raleigh, 2014. p. 221

oldest church in North Carolina, built in part with Salter funds: Duffus, Kevin. "The Last Days of Blackbeard the Pirate" 4th ed., Looking Glass Productions, Raleigh, 2014. p. 246

their plea was rejected, they threatened Captain Brand: Spotswood to Craggs, May 26, 1719. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

worrying Captain Brand with potential legal action:

On March 11, 1719: Spotswood to Treasury, July 16, 1719. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

for around L2,200: Spotswood to Craggs, May 26 1719. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

After covering expenses for the expedition Spotswood sent the profits to England for safekeeping: Ibid.

delivered the reward (about L300): Brand to Burchett, January 26, 1720. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

same amount as Governor Eden's yearly salary: Lords Proprietors at St. James to Daniel Richardson, August 13, 1713. NC Archives Record ID: 21.23.5.37

the more senior the officer, the more shares he received: Allen, Douglas W. The British Navy Rules: Monitoring and Incompatible Incentives in the Age of Fighting Sail p. 213. Retrieved April 24, 2021.

only received seven shillings, sixpence: Admiralty to the Clerk of the King's Council, dated October 5, 1721. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

L60 pound payout, instead distributing it amongst the sailors: Brand to Burchett, January 26, 1720. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

Captain Gordon gave "every farthing": Gordon to Burchett, September 14, 1721. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

doubling the share of Lieutenant Maynard: Admiralty to the Clerk of the King's Council, dated October 5, 1721. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

bonus directly from Governor Spotswood and some of his council: Gordon to Burchett, September 14, 1721. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

bounty offered by the king to the exclusion of their fellow crew: Brand to Burchett, January 26, 1720. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

leading the charge into enemy territory: Cooke, Arthur L. “British Newspaper Accounts of Blackbeard's Death.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 61, no. 3, 1953, pp. 304–307. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4245947. Accessed 8 June 2020

Maynard sourly noted: Ibid., p. 307

“I should never have taken him…": Ibid., pp. 304–307.

"fought like heroes, sword in hand, and they kill'd every one…": Ibid., pp. 304–307.

Ranger in first to go after the pirates: Brand to Burchett February 6 1718-19. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

When the Ranger was only "half a pistol shot" away: Ibid.

killing or wounding 21 men: Gordon to Burchett, September 14, 1721. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

navy's men was actually killed by friendly fire: Ibid.

Maynard had most of his crew - including himself: Ibid.

rope in hand to tether his new prizes: Ibid.

within six minutes, Thatch was dead: Ibid.

140 bags of coco and 10 casks of sugar stockpiled beneath a tent: Brand to Burchett February 6 1718-19. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

another dead pirate, his body caught in the reeds: Gordon to Burchett, September 14, 1721. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

loaded them down with all the plunder: Brand to Burchett February 6 1718-19. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

careful instructions to make sure that none of the pirate's plunder got distributed:

Gordon to Burchett, September 14, 1721. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

and

Brand to Burchett, January 26, 1720. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

The day after Maynard's arrival: Brand to Burchett, January 26, 1720. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

beautiful weather and triumphant nine-gun salutes: Logbook of HMS Pearl, Jan. 3 1719. ViaDuffus, Kevin. "The Last Days of Blackbeard the Pirate" 4th ed., Looking Glass Productions, Raleigh, 2014. p.169

reportedly included gold dust and plates: Admiralty to the Clerk of the King's Council, dated October 5, 1721. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

Captain Gordon had it on good authority that Maynard's portion was worth about L90: Gordon to Burchett, September 14, 1721. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

"tho I believe not to anybody's satisfaction but his own.": Brand to Burchett, January 26, 1720. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

Captain Gordon questioned his lieutenant: Ibid.

Lieutenant Maynard replied that he would answer for himself directly to the Admiralty: Ibid.

The king ordered the profit from Blackbeard's auctioned goods: Response from the king in council to Gordon's petition, October 23-November 3, 1721. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

another 22 years: Dictionary of National Biography (would like to have another citation)

admiral by the time he died in 1759: Brooks, Baylus C. Quest for Blackbeard: The True Story of Edward Thache and His World, Baylus C. Brooks, 2017, Electronic Edition. p. 1299-1300

mortally wounded by robbers: Brooks, Baylus C. Quest for Blackbeard: The True Story of Edward Thache and His World, Baylus C. Brooks, 2017, Electronic Edition. p. 1301

The last documented trace of Israel Hands: Johnson, Charles. A General History of Pirates. Second Ed., T. Warner, London, 1724, p. 87

His chief beneficiary was John Lovick: Retrieved February 2021.

council unanimously voted Thomas Pollock: LaVere, David. The Tuscarora War. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2013, p. 193

Moseley eventually regained: Retrieved April 29, 2021

May of 1720, both Virginia's Governor Spotswood and his council: "America and West Indies: May 1720." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 32, 1720-1721. Ed. Cecil Headlam. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1933. 36-44. British History Online. Web. 15 June 2020. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol32/pp36-44.

“no governor who had been abroad": Alexander Spotswood to John Spotswood, December 21 1724. [Citation misplaced]

Edward Salter bought up considerable parcels of land: "The Last Days of Blackbeard the Pirate" 4th ed., Looking Glass Productions, Raleigh, 2014. p. 173

his descendants took part in the revolutionary war: Interview with Kevin Duffus.

Howards and Salters (not to mention some Jacksons) settled on Ocracoke: Ballance, Alton. Ocracokers. University of North Carolina Press, 1989, p. 21-2

Graphics:

Oath: The Tryals of Captain John Rackham, and Other Pirates. Jamaica, printed by Robert Baldwin, 1721, p. 42

Fate of Blackbeard's crew: Wilde-Ramsing, Mark and Linda F. Carnes-McNaughton. Blackbeard's Sunken Prize: The 300-Year Voyage of Queen Anne's Revenge. University of North Carolina Press, 2018. p. 167